Last Man Standing: The Rise of Homo sapiens

"I, I am the one, the one

Who lost control, control

But in the end

I'll be the last man standing

I, I am the one, the one

Who sold his soul, his soul

Forever gone

To be the last man standing tall" - "Last Man Standing" (2008), Hammerfall

Out of Africa, Version 1.0

Phylogeny of the Homininae, Continued

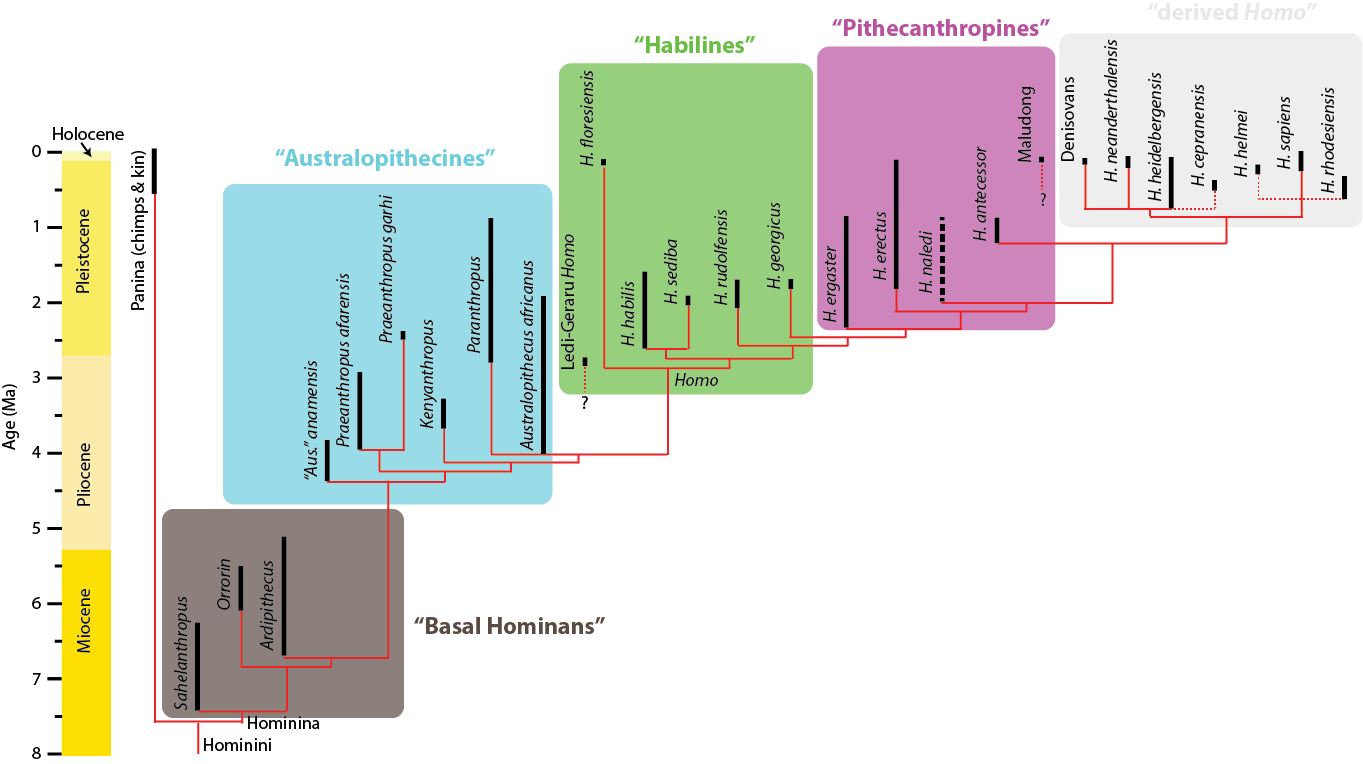

Below is a (possible) phylogeny for Hominina (Homo and all taxa closer to Homo than to Pan), as seen in last lecture:

Eurasian "habilines": "Habiline"-grade species include some of the first to move out of Africa. The 1.85-1.77 Ma Dmanisi, Georgia, site has abundant remains of a small-bodied homininan (or multiple hominan species?). Originally considered early specimens of Homo erectus (and still considered such by some paleoanthopologists of an extremely lumpy variety), others recognize it as a new more basal species: H. georgicus. At this time the rifting between the Arabian and African plates was incomplete, and there was still land connection between the Red Sea and the Gulf of Aden. Additionally, the world was wetter, so that instead of a Sahara and Arabian desert, this region was a relatively-continuous "savannahstan" connecting the African savannas and the steppes of Eurasia. Not just homininans but other African mammals moved into Eurasia at during this interval.

It has to be said, however, that there is considerable variation in the skulls of the Dmanisis homininans, and some studies suggest that multiple species are actually present here. Phylogenetic studies have not resulted in a single consistent position for this material: some place it very basal, at about the same level as Homo floresiensis (which it resembles in size and overall development); other features put it closer to the H. ergaster/erectus-"pithecanthropine" level, and some even suggest it is derived from H. erectus. These alternative positions are reflected in the multiple uncertain placements on the cladogram above.

There is another habiline-grade small-bodied species similar in many ways to H. georgicus but FAR more recent. This is Homo floresiensis, the "hobbits" of Flores Island, Indonesia. These are 1.1 m tall homininans from Indonesia known from fossils that are incredibly young: merely 100-60 ka based on the bony material, and 190-50 ka for their tools. (Until 2016 it was thought they survived MUCH more recently than that: a mere 74 to 12 ka (and tools going back to 95 ka): in other words, they almost made it to the Holocene.) Even with the revised stratigraphy and dates, H. floresiensis is among the youngest non-sapiens stem-humans known: contemporary with almost the last Neanderthals and the "Maludong" people.

The "hobbits" were an island isolated population, and thought initially to be an insular dwarfed form of H. erectus, but details of the skeletal anatomy show that they are fairly basal within Homo. (There is even a school of thought that they are simply abnormally-developed H. sapiens, but this is at odds with both skull and skeletal observations.) Only recently discovered, these specimens hint at a greater diversity of human-line peoples even at the recent past. Phylogenetic analysis places them as nested among "habiline" species such as H. habilis, H. sediba, and H. rudolfensis.

The presence of one definite (and one or more possible additional) habilines within Eurasia in the Pleistocene--including one at the far end of how far you could walk by land during a glacial maximum--suggests that there are other similar forms yet-to-be discovered throughout Eurasia.

"Pithecanthropines": Some have grouped the species of this grade simply into the one species Homo erectus, while in the late 19th and early 20th Century different specimens were placed in various genera (Pithecanthropus, Sinanthropus, Javanthropus, Meganthropus, Telanthropus, Tschadanthropus). We will follow the generally partition of recent paleoanthropological work: the named species (2.27-0.87 Ma African Homo ergaster, 1.85-0.070 Ma truly Asian Homo erectus), 1.2-0.936 Ma European/North African H. antecessor, and two possible "mystery species" (about which more below). However, we will use the traditional grade-name "pithecanthropine" for this phase of human diversity.

A brand-new discovery is Homo naledi of South Africa. Found deep in a cave, this species is still under study. Initially thought to belong in the "habiline" part of the tree, new studies suggest it is higher up among the "pithecanthropines"; however, some paleoanthropologists consider there to be multiple species represented among these fossils. Unfortunately, reliable age dates are not yet available for it: it might be somewhere between 3 and 2 Ma, but newer data suggest an age between 2 Ma and 900 ka, possibly younger.

There is a considerable increase of body size (heights up to 1.85 m are known) and of relative brain size with the rise of pithecanthropine-grade Homo. There is circumstantial (and not always convincing) evidence for the use of fire by these peoples. The diet includes a considerable fraction of meat of large animals, including mastodonts and mammoths. (This trait may go back to more basal forms: even the habiline H. floresiensis seems to have hunted the dwarf species of Stegodon on Flores). The build of typical "pithecanthropines" is far more modern than earlier phases: although not exactly of the same proportions as H. sapiens, their limbs indicate that like us they could engage in long-distance endurance running. (It has been shown that although most African large mammals are faster than humans, we can cover the same amount of distance per day as they can because we are marathoners rather than sprinters.) There are some very good trackways from "pithecanthropines" (even H. antecessor tracks from England) that show their locomotion was essentially modern. So from the hips down, at least, we are dealing with species that are "modern" (unlike the earlier grades of homininans).

Pithecanthropine-grade Homo (and some later forms) are associated with the Acheulean toolkit with its characteristic "hand axe". Acheulean tools are known from 1760 to about 200 ka.

H. ergaster represents the African species of this grade. It is the oldest "pithecanthropine" and might be the likely ancestor of the Eurasian forms. (At one point H. georgicus was considered to be just Eurasian-representatives of H. ergaster.) H. erectus-proper is known from mainland Asia (including the famous "Peking Man" specimens from near Beijing) as well as in Indonesia (the "Java Man" and "Solo Man" fossils). H. erectus is known until about 230 ka on the mainland, and the Java population may have survived to a mere 70 ka! H. antecessor is known from Spain and France, and possibly from some northern African sites.

There are two populations of fossils from China that might represent members of this phase of Homo history. In Dali and Jinniushan (northern China) there are fossils of a robust and large-brained fossils, dating from 260-130 ka. The Jinniushan fossils include a fairly good specimen of a robustly-built female about 169 cm tall and 79.6 kg, with an astonishing cranial capacity 1330 cm2! (This is larger than the average of H. sapiens!) The Dali/Jinniushan species (if they are indeed one distinct species: if so, the proper name would be "Homo daliensis") may be an H. erectus-derived form strongly convergent on H. neanderthalensis. A partial mandible dredged up from near Taiwan (but very poorly dated) might also be from this population. A few workers have considered this simply an extremely eastern population of H. heidelbergensis, or even early members of the H. sapiens lineage.

A second, even younger, but more slender population is known from Maludong (Red Deer Cave), Longlin, and nearby locations in southwestern China. The Maludong people (who do not have a formal taxon name) show a mixture of derived and primitive traits; they may be another group of "pithecanthropines". Of particular note, though, is their extremely young age: the Maludong site is only 14.3-11.5 ka, making these the youngest known surviving hominan species other than Homo sapiens. As will be mentioned later, there is genetic evidence that the Denisovan population had some genetic mixture with a non-sapiens, non-neanderthalensis population: based on geography and timing, this might be that population. (To be fair, at least some paleoanthropologist consider the Maludong just a sub-population of Homo sapiens: however, one wonders if this is based on morphology, or simply the very young age.)

Derived Homo: In the west (Europe and Africa) appeared very large brained hominins. Sometimes termed the "archaic Homo sapiens", these are now typically divided up into various species, such as H. cepranensis of 487 ka Italy; H. rhodesiensis of 700-100 ka Africa (from the north to the south); and 260 ka H. helmei of South Africa. Some paleoanthropologists consider this a single diverse widespread species (under the name "H. heidelbergensis", and some of them consider the Dali and Jinniushan specimens as belonging to this species. These same scientists think that H. neanderthalensis and H. sapiens are thus both derived from this single widespread species.) This complex of species seems to split into two clades: a Eurasian and northern African clade (H. cerpanensis, heidelbergensis, neanderthalensis, and the Denisovans), and the other (initially) strictly African (H. helmei, rhodesiensis, and sapiens.)

The first line is represented by H. heidelbergensis from 700 to 100-200 ka, and its likely descendant species H. neanderthalensis from 197 to about 30 ka (and even younger, <28.5-25 ka, at Gibraltar). Neanderthals has the largest brain size of all hominins (yes, bigger than ours) and were very powerfully built (body strength of a 19th Century weightlifter). They show many unique derived characters lacking in all modern humans, and are almost certainly not our ancestors in general (however, they DID interbreed with humans on occasion: more about this later.) Neanderthals lived in Europe and the Mideast, but even as far east as central Siberia, in cold (but not glacial) conditions. Breaks in their bones match those found in rodeo performers, suggesting that they manhandled large animals. Their tool kit, the Mousterian, was far more sophisticated than the Acheulean. However, it lacked apparent art, nor did it show much in the way of fine tools, nor did it change much over more than 150,000 years, nor did it vary much from region to region.

Neanderthals had a VERY meat-rich diet. In fact, they seemed to have preferred the meat of large animals (horses, woolly rhinos, etc.). Even when they ate food from the sea, it seems to be in the form of beached whales and seals.

Overlap between modern humans and Neanderthals was very brief (less than 6000 years). Some have suggested human-Neanderthal mating, but the evidence is highly problematic and is better explained as common juvenile traits rather than hybrid traits. At the end of their history Neanderthals improved their technology, producing Chatelperronian technology: finer than Mousterian, but still lacking in obvious art except for some probably beads for necklaces.

Neanderthals seem to have held out last of all in southern Iberia (including the rock of Gibraltar).

The sister taxon to Neanderthals are a population known from very few bones but for which we have a lot of genetic material: the Denisovans. The very limited bony material for this group is from 51-28.9 ka. We'll discuss them more in the next lecture.

Likely derived from Homo rhodesiensis, the oldest specimens of true Homo sapiens date to about 250 ka (for problematic specimens), and definitely by 160 ka. We can be fairly confident that H. sapiens is around by about 200 ka. Anatomically modern humans are present in Africa from this point onward, and there are some in Israel from 100-80 or 70 ka, but this latter population seems to die out. New (April 2014) evidence suggests that a population left Africa around 130 ka along the southern margin of Arabia, hugging the coastal regions of southern and southeastern Asia, and eventually colonizing Australia (by about 42 ka). The oldest Asian fossils of Homo sapiens (from South China) is from about 80 ka, and may also represent this phase. A third "out of Africa" phase (at around 50 ka) is the main population to colonize Europe, most of Asia, and from there the rest of the world.

Anatomically, H. sapiens is distinct from H. neanderthalensis and H. rhodesiensis (and other relatives) by:

Elimination Rounds

Taking a look at the above information, we can track the number of species of Homo present for the last 200,000 years:

The appearance of these behavioral traits has been called the "Great Leap Forward" by Jared Diamond. Around 50 ka or so we see the rise of representational and symbolic art, finely-made tools, and the like.

What caused (or allowed) the Great Leap Forward? It was once thought be associated with the evolution of a mutant FOXP2 gene, which allows fine motor control of the mouth and tongue. The modern human version of this gene is missing in all other living primates, and seemed to have appeared no earlier than 200 ka (i.e., long after the split between the ancestors of H. sapiens and the H. heidelbergensis-H. neanderthalensis line. However, with our understanding of the Neanderthal genome, it appears these peoples had the same version of the FOXP2 gene we do.

ALL modern humans are descended from African populations; we are all the scatterlings of Africa. Some voyages (throughout Europe and continental Asia, into glacial lands, over the land bridge to the New World) were on foot. Unlike other homininans, we have a substantial amount of seafood in our diet: fish, shellfish, and the like. So many human cultures lived near the coastline. (Incidentally, since much of H. sapiens history is within a glacial rather than an interglacial, sea levels were much lower then, and most of the coastal sites of those time are now underwater.

Additionally, H. sapiens seems uniquely to be a boating species. Modern humans reached Australia by 42 ka, but there was no land connection at the time; in contrast, the Neanderthals never made the much shorter crossing from Gibraltar to Africa. And boats may have helped humans colonize the New World: controversially as early as 30 ka, unquestionably by 13 ka, quite reasonably around 18-16 ka.

Arrival of modern humans (or at least modern humans equipped with certain levels of technology) seems to result in mass extinction of many local animals: around 46 ka in Australia; around 14 ka in glacial Eurasia; around 11-13 ka in the New World; and many, many times in islands around the planet.

From the point of divergence from the ancestors of chimps through all this times, humans seem to have lived in small bands. Comparisons with both non-agricultural human societies and with non-human hominids suggests these were almost all bands of about 30 or so at most, made up of closely related individuals: everyone would be a first or second cousin. There would be occasional exchange of genes between neighbors, but aggression between them would help maintain cultural and linguistic separateness. At the larger end would be tribes: units of a few hundreds, still closely related by birth and maintaining identity by means of unique customs, languages, and a near constant state of low-level "warfare" (although having far more in common with "drive-bys" than with later wars). The ability for any one band/tribe to conquer or absorb another would be relatively limited.

Food acquisition would be various combinations of hunting and gathering (collectively called foraging). Foragers can have a very good diet, but in order to expand a population it has to grow by "extensification": spreading out to new lands. (Later on, humans develop methods of "intensification": increasing the productivity of the land, ultimately becoming animal husbandry and gardening.) Because of a reliance on extensification, and our amazing tolerance to different environmental conditions, H. sapiens began to spread out to all corners of the world.

We can now answer many questions about human origins with great degree of certainty:

So think about it: our physical bodies, our physiologies, and our behaviors evolved in conditions that nearly none of us now live!

To Lecture Schedule

Back to previous lecture

Forward to next lecture