"Why then is not every geological formation and every stratum full of such intermediate links? Geology assuredly does not reveal any such finely-graduated organic chain; and this, perhaps, is the most obvious and serious objection which can be urged against the theory." -- Chapter 9 "On the Imperfection of the Geological Record", On the Origin of Species by Means of Natural Selection (1859), Charles Darwin

"Since we proposed punctuated equilibria to explain trends, it is infuriating to be quoted again and again by creationists -- whether through design or stupidity, I do not know -- as admitting that the fossil record includes no transitional forms. The punctuations occur at the level of species; directional trends (on the staircase model) are rife at the higher level of transitions within major groups." --The Panda's Thumb (1980), Stephen Jay Gould

BIG QUESTION: How do new species form?

Speciation: The Pattern of the Origin of Species

As with many things, we run into problem with typological thinking: the idea that there are ideal types of things, and that we judge a specimens membership in a group by how well it conforms from that type. Instead, we find that variation is the reality. So we need to use population-based thinking. (Next lecture we will add tree-based thinking.)

Darwin's species concept is worth revisiting:

An important issue which is commonly forgotten comes out here: descendants are descendants of only a small part of any ancestral group! That is, entire species do not evolve into entire other species. Instead, only some small subset of any given species population is the ancestral group leading to a particular descendant. This points to several different aspects:

Note: this relates to a common anti-evolutionary rant, which goes a long the lines of "if people evolved from monkeys, how come there are still monkeys". Ignoring lots of other problems with this statement (such as the fact humans didn't evolve from any living monkey species; that "monkeys" aren't one thing, but are a vast number of species; etc.), this misses important aspects of how evolution works! Just because some monkeys evolved into apes which evolved into humans does not require that ALL monkeys evolved into apes and ALL apes evolved into humans. Plus, it doesn't mean that monkeys were TRYING to evolve into humans, or DESTINED to do so.

(Here's a way to restate an analogy to this anti-evolution argument: "If [for example] your ancestor came from Ireland (or Norway, or India, or whatever), why are there still Irish/Norwegians/Indians/etc.?")

Adaptive (or Fitness) Landscapes

One metaphorical device that is sometimes useful to use when talking about evolution is the idea of an "adaptive landscape" or "fitness landscape". Imagine all the variables in an organism's circumstances reduced to a surface with peaks and valleys. The height of the peak reflects the fitness of the organism. Evolution will always favor populations moving "uphill" (increasing fitness). But they can only move to the nearest peaks through ordinary selection, even if there are higher peaks elsewhere. That is because moving downhill would mean a decrease in the fitness of the descendant populations. So selection only moves towards "local" optima in normal situations.

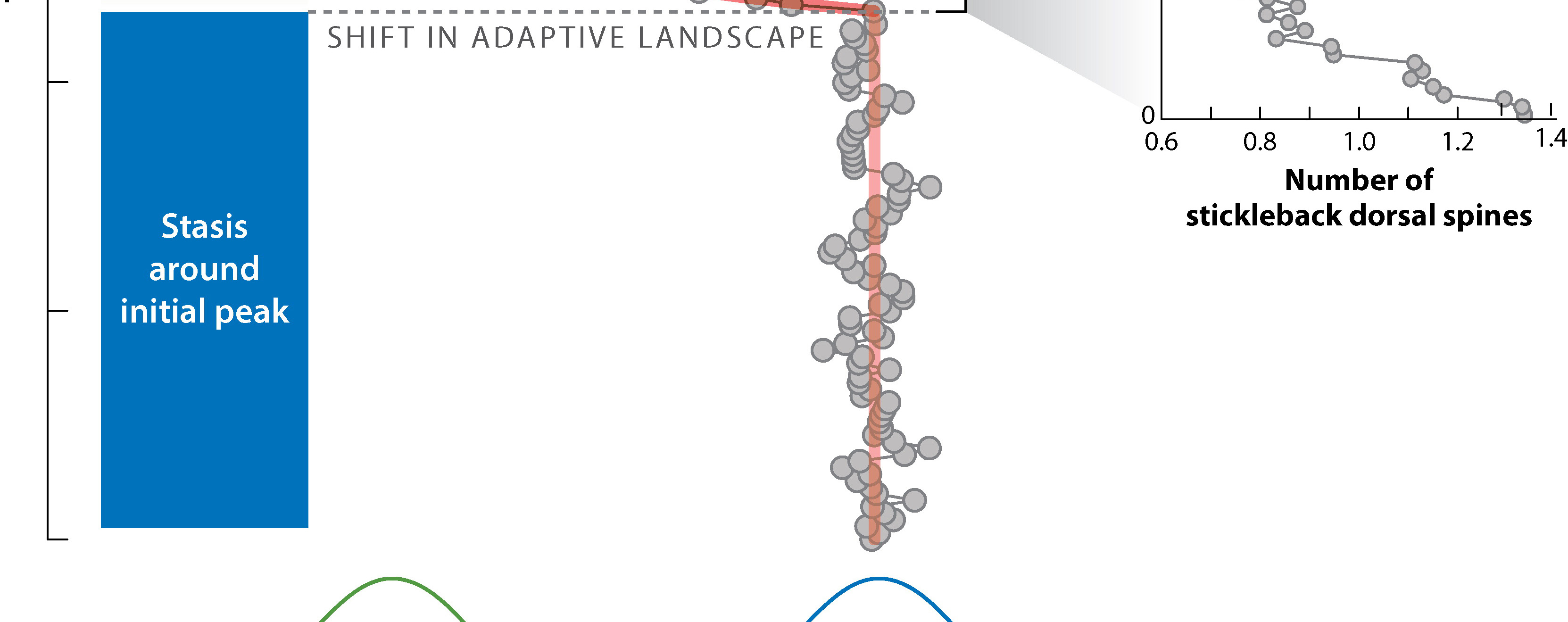

However, large mutational "jumps" might place a descendant on a point on the landscape far from its ancestor, allowing it to move to adaptive peaks not accessible to the earlier forms. And the landscape itself "shifts", because the environment in which the organisms exist change, meaning what controls "fitness" will be different over time.

Speciation is the process of the origin of a species. It doesn't happen immediately or instantaneously: it is indeed a process rather than an instantaneous event. (In fact, except in rare cases, it is unlikely that it you there during it that you would recognize it as such.)

Some aspects of the origin of species to consider:

During the 20th Century (especially during the first half), evolutionary biologists assumed the dominant trends were sympatry and anagenesis. However, as a better understanding of genetics was developed, some (including Mayr) argued that allopatry, peripatry, and parapatry (which all require cladogenesis) were actually more common.

The problem, of course, is that speciation takes time, and field biologists are unlikely to observe it. If only there were some sort of record of changes over time. Say, for example, a fossil record...

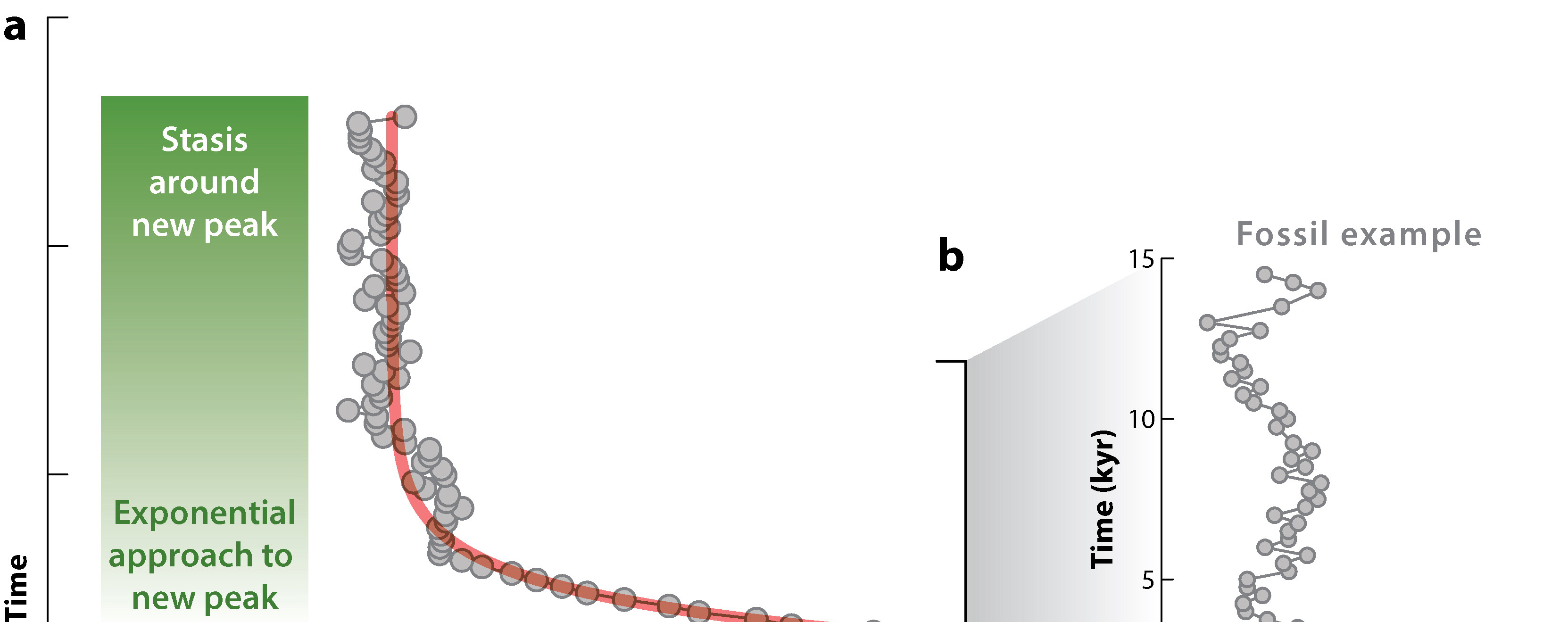

In 1972 paleontologists Niles Eldredge and Stephen Jay Gould proposed an alternative, which they called punctuated equilibrium.:

The punctuated equilibrium model helped explain some aspects of paleontology. As Darwin noted (see quote at top), we do not see an endless series of slight gradations, each stratum with a slightly different version. Instead, species remain largely unchanged for most of their duration, with new closely-related species appearing suddenly in the fossil record. In fact, if it weren't like this, biostratigraphy would not really work! As the punctuated equilibrium supporters argued, "stasis is data".

During the 1970s and 1980s (and continuing today, but at with much less rancor), the debate over "evolution by creeps" vs. "evolution by jerks" continued. At least in the fossil record, punctuated equilibrium seems

How long are punctuation events? In a rare case, Smithsonian paleontologists Gene Hunt, Michael Bell, and Matthew Travis found that a population of the stickleback species Gasterosteus doryssus got isolated in a lake in Nevada in the Miocene Epoch. In this particular case, there were annual layers, allowing them to measure an excellent sample over time and document its change. They found the period of transition from the ancestral form to the descendent took only about 2000 generations (about 4000 years), after which the population was mostly stable. Events on the 103 year scale are unlikely to show up in the fossil record except in such situations (high sample size, restricted location, annual record), as the fossil record is much better at picking up events at the scale of 104, 105, or greater.

Supporters of the punctuated equilibrium model had to wonder how equilibrium was maintained. Evolutionary stable scenarios seem to be at least part of the reason.

Why the punctuations? A likely cause is that environmental changes are rather quick on the geologic time scale, with stable conditions in between. Rapid shifts in climates will result in shifting population ranges, shifts in habitat availability, etc. This leads to the prediction that we should see evolutionary shifts (speciations, extinctions, etc.) concentrated at moments of environment change: the so-called "Turnover-Pulse Model".

In summary, punctuated equilibrium may well be due to the following combination of aspects:

A historical note: a close read of The Origin shows that Darwin did consider cladogenesis and parapatry/peripatry as critically important in most speciation, and that anagenesis of the main part of the ancestral population was almost never the case.

The term is problematic for a couple reasons:

So it has a very small chance that given fossils are the ancestors of the species you are interested in. However, it might well be a more general early relative, and that could be useful indeed.

Darwin pointed out that there is not the continuous series of transitions that might expected from a gradualistic model of evolution in the fossil record, but noted that the fossil record was great for higher-level transitions. And this record is vastly better now than in the 1850s!

Here are a handful of interesting transitions recorded in the fossil record:

Some important thing to note about these:

"Intermediate forms" is another related term used in the field. Basically, however, every taxon is intermediate between its closest relative and the groups more distantly related.

An important thing to revisit before we move on: the specter of typological thinking. Our minds like to think of discrete types of things. However, when dealing with evolution, there is a continuum of form from one to another. Remember: at no time did a mother of one species give birth to a daughter of another species! It is only from a distance in time do we see the accumulation of changes.

This applies for groups above the species as well. At not moment in the history of life would you witness a population of one major group giving rise to a population belonging to another major group. It would always look just like ordinary speciation. It is only from a distance that we see the Tree of Life.

We have already seen correlated progression (the summed affect of adaptions consistent with a particular mode of life) and divergence (the splitting of one ancestral group into two or more distinct descendant lineages) as examples of macroevolution. Here are a few more: