"Given extensive paleontological evidence for biotic change, the conclusion must be that, absent such long-term perspectives, most biological benchmarks--for abundance, distribution, variability, drivers, and dynamics--and rate estimates that are embedded within the last 50-100 y are probably far from natural. Natural may not be an achievable or desirable goal. However, paleobiological data for the recent past confront us with the true status of modern-day biota and with the very real potential that climate-driven changes will result in elevated extinctions rather than community disruptions alone, owing to the continued press of other human factors and damage already sustained. Paleontological data, derived both from fully buried fossil assemblages and from death assemblages that are still accumulating alongside living populations, constitute a powerful source of insights into the dynamics of extant (and recently extinct) species, communities, and ecosystems over the interdecadal to millennial time frames at which environments undergo natural and human-driven change. Improved environmental proxies, age-control, and confidence in paleobiological evidence mean that disparate data types should no longer impede the development of a rigorous "Biology in the Anthropocene" that squarely faces legacy effects, ongoing trends, and disequilibrial states as default conditions. We should in fact embrace the modern world as an unnatural experiment in progress, no matter how uncomfortable our eventual discoveries may prove to be, and commit to greater integration of modern and paleo approaches in both research and training. The fossil record's future includes its ability to provide critical data and new time frames for conservation, management, and ecological theory." -- Susan Kidwell (2015. Biology in the Anthropocene: challenge and insights from the young fossil records. PNAS 112:4922-2929.)

BIG QUESTIONS: How does the fossil record inform us about the on-going modern extinctions?

What Good is a Fossil Record?

That is to say, what benefit does society receive from the existence of fossils of the ancient world? There are many of them that are scientific, or even aesthetic:

But are there any pragmatic benefits? YES!

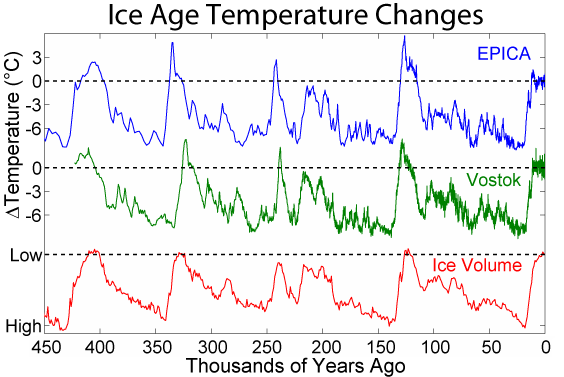

Compared to the earlier Pleistocene Epoch, the Holocene has been an epoch of climate stability. It was rare in the Pleistocene to have a 12 kyr warm pulse with only a degree or two of average change; instead, we see fluctuations of up to 7-9 C°:

And all our agricultural, freshwater, coastline, etc., needs were developed in the context of this period of stability.

Agriculture has allowed human populations to soar:

Agriculture allowed humans to capture more and more of the land's biomass. Also, as agricultural lands expanded, wildlife tended to be displaced, bringing their population down. Furthermore, wild species of animals were domesticated into new forms (aurochs into cattle; boars into pigs; mouflon into sheep; wild goats into goats; wild horses into horses; wild asses into donkeys; etc.): the wild species tended to decline from habitat loss and hunting while the domestic forms flourished under human husbandry.

The colonization of the Brave New Worlds (Sahul and the Americas) was not the end of the expansion of Homo sapiens. During the Holocene humans spread to many oceanic islands in the Pacific, Indian Ocean, and elsewhere. In the wake of new arrivals, many species became extinct. For example, the total number of bird species at 1 CE was probably 3000 more than today, largely do to losses of island avian species.

Let's take a look at some of the patterns of extinction.

Historic Cases Recognized at the Time:

But there are many other larger-scale or more dramatic extinctions during the Holocene:

Madagascar: Humans (settlers from Borneo, rather than nearby southeastern Africa) reached the island of Madagascar between 350 and 550 CE. They arrived with an agricultural system based on slash-and-burn. Through a combination of habitat destruction and direct hunting, they wiped out such as:

New Zealand: These islands remained uninhabited until 1280 CE, when Polynesians first arrived. By 1400 (possibly before) they had wiped out many taxa, including:

In the case of the moa there is direct evidence of hunting and feeding by humans, and this seems likely in the case of the adzebills, too. The Haast's eagles were probably victims of trophic collapse: with the moa gone, there was no targets left (other than men) large enough to serve as prey.

Tasmania: Part of Sahul, it was isolated from mainland Australia as the sea rose in the last deglaciation. Its inhabitants lost a substantial part of earlier technology, such as bone tools, boomerangs, hooks, sewing, and the ability to start fires. In many ways, they had reverted to Homo erectus-grade technologies. In Tasmania some of the larger animals that were wiped out on mainland Australia survived, most famously the thylacine or Tasmanian tiger or Tasmanian wolf (Thylacinus cynocephalus. This animal was a marsupial predator strongly convergent on placental wolves. With the settlement by Europeans in 1803, a systematic campaign of extermination of both the Tasmanian people and Tasmanian tiger began. Sadly, both were successful. The native population of Tasmania was hunted down to the last individual and their language and culture lost for all time: the last full-blooded Tasmanians were the women Truganini who died on 8 May 1876 and Fanny Cochrane Smith who died in 1905. The thylacines actually survived longer, with the last specimen dying in captivity on 7 September 1936. Below is a compilation of all surviving film footage of this species (all of it in zoos, rather than in the wild):

The mainland Old World: But these are all small, isolated lands. Surely extinction hasn't happened in recent times on the continents? Sadly, here to. For example, the quagga (Equus quagga quagga, an extinct southern African subspecies of plains zebra: 12 August 1883), the aurochs of Eurasia (Bos primigenius, although technically a pseudoextinction as the domestic cow Bos taurus is a descendant: 1637), the tarpan of Eurasia (Equus ferus ferus, the ancestor of the domestic horse Equus caballus: 1879 for the last scientifically verifiable non-hybrid), and others. And the extinctions in North America were particularly striking.

Continental North America: Here the extinctions included not only rare forms, but some of the most common species to inhabit the continent:

A very, very close call was Bison bison, the plains bison, largest and by far most common large mammal of North America after the megafaunal extinction. Their huge herds made them essentially hunt-proof to the Folsom points--and later bows and arrows--of Native Americans. But arrival of advanced rifle technology, the expansion westward of American farming and railroads, and a tremendous market for bones for fertilizer and hides for many numerous uses led to commercial hunting on a phenomenal scale, bringing species dangerous close to extinction at the end of the 19th Century. Once hundreds of millions formed vast herds, but by 1890 less than 1000 individuals remained. Political and social action from the grassroots on up to Congress and the White House led to protection of this symbol of the American West, and the species was saved and once again roams the West.

20th Century: Beginning of the Sixth Mass Extinction: But all these pale in comparison to the widespread ecological devastation of the 20th and 21st Century. The huge increase in human population, and the requirements to feed this population and supply us with homes and products, means we impact the biosphere on an ever-increasing scale:

It is no longer direct hunting that is the major issue (although still ongoing on land in the form of the pet trade, trade in exotic animal products like ivory, and slaughtering rare species for "traditional Eastern medicine" ingredients). The primary dangers are:

It has been argued that the net result of this is that Earth is in the sixth major mass extinction, as the impact now includes the marine realm, small organisms, etc. (and not just the megafauna). Like all mass extinctions, this stems from the fact that the environmental changes are happening faster than organisms can evolve to adapt to them. Although extinction rates are no where near the level of the Big Five, we have instigated the same type of causes that happened before (extreme eutrophication, like the Ordovician-Silurian and Devonian-Carboniferous; ocean acidification, at least a partial contributor to the Permo-Triassic and Triassic-Jurassic [and PETM]).

A somewhat unexpected recent (as in April 2018) discovery is that the general public greatly underestimates the predicament of the better known and "charismatic" species. That is, some species which are overexposed publicly (such as giraffes and elephants) are assumed to be less threatened, whereas in reality they have had catastrophic population crashes in the last several decades. Below is seen the percent loss of species over time on the left, and the percent who incorrectly answered the question "Is this species endangered?" (correct answer for all is "yes"):

from Courchamp et al. (2018 PLoS Biology 16(4): e2003997

Modern conservation ecologists now refer to defaunation: a combination of global extinction, regional extinction (aka "extirpation"), and population decline.

Defaunation isn't the only change (or at least not directly). Climate change means that when different temperatures reach different spots in a year during its annual cycle; so the preferred seasonal ranges for animals or growing zones for plants change. This might result in changes in the phenology (seasonal life cycle events) of different species: sometimes this disrupts the evolved patterns of growth and development.

Additionally, there are trophic cascades and other ecosystem cascades by the loss of key species within an ecosystem. In trophic cascades, loss of apex predators removes checks on the large herbivores, which may result in overfeeding by these, reduction of plant diversity, etc. Sometimes the effects can be even more complex. Ecosystem cascades are the more general category. We saw with the loss of the mammoths, the mammoth steppe biome with its high diversity was lost. Similar changes are seen in the modern world as "architect" animals are removed.

And for our own parochial interest: the living world provides ecosystem services: activities which are beneficial (or even required) for human life and economy, but for which we do not pay. Some such benefits are:

If you are made of stern stuff, you can check out the very well-done documentary Racing Extinction