Key Points:

•The greatest mass extinction of all time--the Permo-Triassic Extinction of 252 million years ago--ended the dominance of the therapsids. In the Triassic Period the sauropsids, and especially the archosaurs, become most successful.

•The Pseudosuchia (the crocodile lineage) was the most successful group of archosaurs in the Triassic.

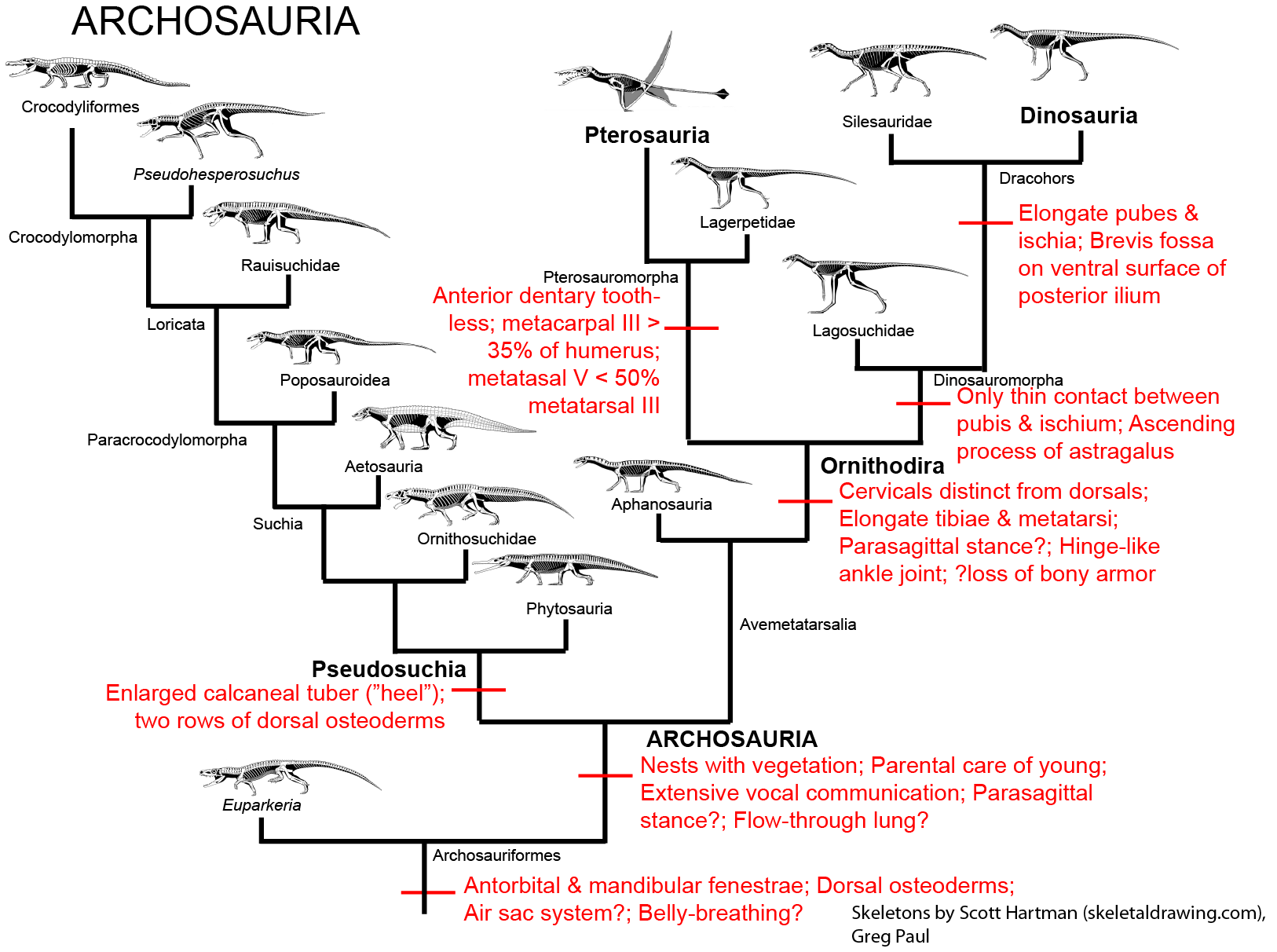

•Dinosaurs are nested with the increasingly exclusive groups Avemetatarsalia, Ornithodira, and Dinosauromorpha.

•There is a shift towards obligate bipedalism, parasagittal (upright) posture, digitigrade stance, a grasping manus, and a perforate (open) acetabulum on the lineage up to Dinosauria.

•Dinosauria is comprised of three major clades: Ornithischia, Sauropodomorpha, and Theropoda. Traditionally, sauropodomorphs and theropods were recognized to form a clade Saurischia. However, recent discoveries have reduced the support for this hypothesis, and alternative relationships are possible. Notably, the possibility of a theropod-ornithischian clade Ornithoscelida is supported in some recent studies.

•Another point of contention is the position of Silesauridae. Traditionally they were considered the sister taxon of Dinosauria, but now several recent studies place them as a paraphyletic grade of basal ornithischians. Thus the traditional dinosaur traits are in fact convergently evolved between Saurischia and the non-silesaur ornithischians (Prionodontia or Saphornithischia)

•There are several Triassic (Herrerasauria; Eodromaeus; Tawa + Chindesaurus; etc.) and even Jurassic (Chilesaurus) dinosaurs whose position within the clade are presently very uncertain.

I. The Triassic Reptile Radiations

At the end of the Late Permian, the greatest extinction in the history of life clobbered ecosystems on land and sea. This event totally changed the make-up of the diversity of life, and forms the boundary between the Permian Period of the Paleozoic Era and the Triassic Period of the Mesozoic Era. Consequently, it is called the Permo-Triassic Extinction. Perhaps 95% of all species died out.

The cause seems to ultimately have been the Siberian Traps, a monumentally huge series of volcanic eruptions. After a pulse of world-chilling sulfate aerosols plunged the Earth's surface into near-Ice Age cold, the massive amount of greenhouse gases raised global temperatures through extremes of greenhouse gasses; this further triggered additional greenhouse gasses being released from the sea floor. Together, extremes of temperature and of carbon dioxide and very low levels of oxygen on land and sea (and quite possibly extreme acid rain, the loss of the ultraviolet-shielding ozone layer, and more) caused mass deaths.

Regardless of precise scenario, extinction reorganizes the world. In the immediate aftermath, there was a great reduction in size and diversity of the animals present.

Lost were many of the primitive therapsids and many of the primitive reptiles.

During the Early Triassic diversity started off very low in land and sea, and recovered over the next ten million years or so. On land, derived cynodonts (advanced carnivorous therapsids) were the dominant predators, and piglet to ox-sized herbivorous dicynodont therapsids were common. But the sauropsids began to radiate into the number of different forms:

These new predators were the precursors of Archosauria ("ruling reptiles"), the dominant group of Mesozoic sauropsids.

Archosaurs and their closest relatives are distinguished from other sauropsids by:

It is not certain if these early archosauriforms had the behavioral traits found in both the living groups of Archosauria (that is, crocodylians and birds). Because both crocodylians and birds share the following derived traits, however, it is fairly certain that at least the concestor of all Archosauria had them, and passed them on to its descendants:

A great diversity among Triassic reptiles, though, were archosaurs. During the Middle and Late Triassic, the archosaurs displaced the therapsids as the dominant group of large terrestrial amniotes.

Archosaurs are divided into two main branches:

It is the pseudosuchians which dominated the Middle and Late Triassic. This group radiated into a number of forms:

The pseudosuchians include some of the first terrestrial animals to exceed the size of oxen and hippos. Most of them could stand with a semi-erect posture of the limbs, and a few had the fully-erect (that is, parasagittal gait).

Although pseudosuchians may have been the dominant group, plenty of other forms abounded in the Middle and Late Triassic. These included the last and largest dicynodont therapsid herbivores; more advanced, but generally small therapsids (including the oldest mammals: more about them later); many non-archosaurian sauropsids (see above); and...

The First DINOSAURS!

II. Origin of the Dinosaurs

Modern birds and all archosaurs closer to them than to crocodilians are the Avemetatarsalia (bird metatarsals). Just recently (2023) a primitive armored avemetatarsalian Mambachiton of Middle Triassic Madagascar was named; more derived avemetatarsalians lost body armor (although some dinosaurs re-evolved it!) Otherwise the most basal branch of avemetatarsalians are the Aphanosauria ("hidden reptiles"). Only recognized in 2017, these were medium-sized (2-3 m long or so) quadrupedal, long-necked Middle Triassic archosaurs. Best known of these is Teleocrater of Tanzania.

The remaining avemetatarsalians belong to the Ornithoidira ("bird necks"). These started as small-bodied animals that evolved under the shadow of their pseudosuchian cousins, differing from typical sauropsids by having:

The primitive ornithodirans were traditionally grouped as a paraphyletic grade of "lagosuchians" (literally, "bunny crocs"). These "lagosuchians" included the primitive members of both clades of Ornithodira:

The other major branch of ornithodirans are the dinosauromorphs. The oldest dinosauromorphs are known from the earliest Middle Triassic in terms of body fossils, but footprints show that some very small dinosauromorphs (or are these some other ornithodiran??) were present as early as the Early Triassic. Dinosauromorphs are recognized by:

The combination of these various traits allowed the little dinosauromorphs to run and accelerate in a bipedal mode all the time, not just at top speeds like typical sauropsids. The parasagittal gait and hinge-like ankle also allowed dinosauromorphs and early pterosauromorphs the ability to move more actively and constantly rather than only in short bursts of speeds; thus, they were striders. Additionally, although early ornithodirans were small (~30 cm long for Lagosuchus, 1-3 m long for "silesaurs" and other basal dinosaurs, etc.), the presence of limbs directly underneath the body meant that this lineage to grow to much larger size than any previous clade while still remaining terrestrial and mobile (sprawlers relegated to a semi-aquatic life if they became too big to support their weight).

Early dinosauromorph lineages were typically a meter or less long. These were the lagosuchids, such as Lagosuchus (once also called "Marasuchus") and (possibly) Saltopus (which might actually be a basal "silesaur"-grade ornithischian dinosaur).

II. Dinosaur Groups and Relationships

Simplified cladogram of Dinosauria, using the traditional model (e.g., Saurischia is monophyletic; Silesauridae lies outside Dinosauria)

Up until recently, the "silesaurs" (more about them shortly) and Nyasasaurus were found to be the closest relatives to Dinosauria, but not actually be true dinosaurs: that is, they lack the shared derived features expected in the concestor of Iguanodon, Diplodocus, and Megalosaurus and its descendants. (But see below.) Those features (the shared derived features of Dinosauria) are:

A possible shared derived feature of Dinosauria (or even Ornithodira) is the presence of at least some fuzz rather than scales. This rather startling concept is because basal members of one lineage and more derived members of the other show the presence of such structures. While many dinosaurs are preserved with impressions of scales, there are several with other forms of integument. These include:

At present we have no definite evidence of fuzz or other non-scales in sauropodomorphs. But it is possible that a dinosaurian evolutionary novelty is the ability to generate at least some quill, tuft, or branching integument rather than just scales. However, different clades of dinosaurs express this ability in different fashion.

But wait!!! As we will discuss later in the course, pterosaurs ALSO have a fuzzy body covering! If this is homologous to what we see in dinosaurs, fuzziness is a trait for Ornithodira, not for Dinosauria.

A very recently described possible shared derived character uniting all dinosaurs is a newly recognized cheek muscle or sheet of connective tissue, the exoparia ("outside cheek"). Unlike other sauropsids, dinosaurs show signs of a tissue sheet connecting the jugal to the posterior portion of the external surface of the maxilla. Its exact function (and indeed, whether it was just connective tissue or a full muscle) isn't certain at present.

Under the traditional model, all early dinosaurs were all around 1-2 m long bipeds with grasping hands. Footprints that might come from dinosaurs are found in the Middle Triassic of Argentina, but these may be from early members of the dinosaur lineage that evolved before the origin of Dinosauria proper.

Dinosauria contains three major clades:

Until recently essentially all dinosaur researchers considered the most basal split in Dinosauria to be between Ornithischia and a clade named Saurischia ("lizard hips"), the latter defined as Megalosaurus, Diplodocus, and all taxa closer to these taxa than to Iguanodon. However, recent studies call into question that relationship: we'll go into that in a little more detail shortly.

We'll look at the shared derived characters of Sauropodomorpha and Theropoda in later lectures. But let's look a bit at the base of Ornithischia, because new insights about this have radically changed the make up of Dinosauria.

Phylogeny of Dinosauria, under the "Silesaurs are early Ornithischians" model:

More detailed phylogeny of Avemetatarsalia, with concentration on the early dinosaurs (and following new models where the "silesaurs" are basal Triassic ornithischians)

During the last several decades, a number of dinosauromorphs were discovered that seemed to lie outside Dinosauria but represented its closest relations. These were considered a monophletic group, the Silesauridae. These were quadrupedal animals typically about 1-2 m long (although fragmentary remains of one at least 3 m long has been found in Tanzania). They and dinosaurs were traditionally interpreted as forming the clade Drachors ("cohort of dragons"), and share the specialization of elongate pubes and ischia (which may have aided in increased respiratory ability: more air per breath) and a depression called the brevis fossa on the bottom of the posterior half of the ilium (this space is for one of the major power muscles for the hindlimb: in this illustration the label brv points to it, but since this is lateral view you don't see the depression there).

The most primitive silesaurid, Lewisuchus, was carnivorous, but most silesaurids were herbivores. Silesaurids had been known from teeth and bones of the Middle and Late Triassic from around the world, but had been thought to be from primitive dinosauromorphs, ornithischians, sauropodomorphs, and/or theropods until the more complete specimens of Asilisaurus and Silesaurus itself let people know what this group looked like. At least some have a toothless portion of the front end of the dentary, likely covered by a rhamphotheca (beak).

There are a number of derived features of the teeth and jaws shared by Ornithischia and silesaurs. The traditional interpretation is that these are convergences, since silesaurids like the classic shared derived characters of Dinosauria (obligate bipedality, grasping hands, perforate acetabulum, etc.). But since 2020 more and more analyses actually place "Silesauridae" as a paraphyletic series of basal branches in Ornithischia, with carnivorous Lewisuchus as the oldest member and Pisanosaurus as the transition between traditional "silesaurids" and traditional ornithischians. An advantage of this hypothesis is that it explains where the Triassic ornithischians are. However, if true then the features regarded above as the classic shared derived dinosaurian traits (such as the modified hand and the perforated acetabulum) evolved independently in derived ornithischians (Prionodontia or Saphornithischia) and saurischians. I've been cautious about using this hypothesis in class (particularly because of all the convergences needed between traditional ornithischians and saurischians), but since so many recent studies support it, I'm provisionally following it here. Perhaps some day this will all be better resolved.

Simplified cladogram of the "classic" Ornithischia (Prionodontia or Saphornithischia):

Other than silesaurs, ornithischians are extremely poorly known in the Triassic. Since the 1970s the oldest and most primitive ornithischian was thought to be Pisanosaurus of the early Late Triassic Argentine Ischigualasto Formation. The fossil is incomplete, so many aspects of its anatomy are uncertain. Analyses in 2016 and 2017 supported it as a silesaurid, but the latest reanalysis shows it is indeed a Triassic ornithischian AND the last of the "silesaurs"!

Pisanosaurus plus Prionodontia is characterized by the following traits:

Prionodontia (also called Saphornit..., okay, I've said that enough: we'll use the old name "Prionodontia" from now on) is characterized by:

Based on their tooth form and (later) the retroverted pubis, all ornithischians more derived than Lewisuchus were herbivorous. (That doesn't mean that they were exclusively plant eaters, of course! In the modern world, many "herbivorous" sauropsids and mammals eat some meat.)

Simplified cladogram of Saurischia:

Saurischians are named after a primitive trait ("lizard hips" = "forwards-pointing pubis"; the ancestral condition), but they are in fact united by some shared derived traits. These include modifications of the snout and of the vertebrae: however, these are rather technical features and we're not go into them in detail in this course. Additionally, some of the traits long thought to be basal saurischian traits are now popping up in early ornithischians and in silesaurs, and so are not actually saurischian shared derived characters.

The Middle Triassic Tanzanian dinosaur Nyasasaurus. Incompletely known, what data is available shows that it is either a dinosauromorph close to Dinosauria or (possibly) one of the oldest known dinosaurs, possibly a saurischian. (At least one study provisionally put it quite far up the dinosaur tree, as a massospondylid "core prosauropod". If true, this would mean a tremendous part of the diversification of Dinosauria had occurred by the Middle Triassic that is not yet documented in the fossil record.) Like prionodontians and saurischians (but NOT "silesaurs") it has an expanded deltopectoral crest on its humerus.

The saurischians were more common in the Late Triassic than their ornithischian sisters. The theropods include the long-necked herbivorous Sauropodomorpha and the (ancestrally carnivorous) Theropoda. There also appears to be a clade or paraphyletic series of Triassic carnivorous saurischians (Herrerasauria) that branches off before the sauropodomorph-theropod clade Eusaurischia. Among other traits shared among the saurischians are:

(A special note: Owen's Dinosauria traits re-examined: If we look at some of the traits that Owen used to recognize Dinosauria, we now find that some were actually inherited from pre-dinosaurian ancestors (e.g., parasagittal stance, from the early dinosauromorphs) and others evolved convergently between Iguanodon, Hylaeosaurus, and Megalosaurus (giant size; more than two sacrals). Still, even though the traits to recognize them have changed, we still use the name "Dinosauria" to unite these reptiles.)

Herrerasauria, is an exclusively Late Triassic group known from South and North America, Europe, and possibly India. These are larger than the other earliest dinosaurs: 3 m or so long, with deep skulls. However, herrerasaurs were not the apex predators of their environments, as larger pseudosuchian predators dwarfed (and presumably hunted) them. Many early studies put them as basal theropods; other as basal saurischians; still others as basal sauropodomorphs (including some analyses that support the "Ornithoscelida" hypothesis); and yet more as outside Dinosauria proper. (It would be convenient in at least one way if they are the sister group to Dinosauria: they only have two sacral vertebrae, making the classic dinosaur synapomorphy "three or more sacrals" problematic when they are within the group...)

Some of the most comprehensive latest studies find herrerasaurs to be saurischians outside of Eusaurischia. They include the more robust Herrerasauridae and a newly discovered possible slender North American clade containing little buck-toothed Daemonosaurus, New Mexican Tawa, and its likely sister-taxon Chindesaurus. These latter two share several features with basal theropods such as a kink between the maxilla and the premaxilla (often with a corresponding large dentary fang below): this was likely a spot to hold onto narrow prey (modern crocodilians with a similar snout pattern do the same). Additionally, various hindlimb traits are shared between Tawa, Chindesaurus, and theropods. These are long-necked, long-limbed, slender animals. Future work will show if these are truly herrerasaurs, if they were closer too Eusaurischia than to true Herrerasauridae, or if they are instead early theropods.

Eusaurischia (the sauropodomorph-theropod clade) is supported by various traits:

The Traditional Phylogeny is Challenged: Ornithoscelida: The dinosaur research community was rocked in March 2017 by a paper by graduate student Matthew Baron and his advisors. They presented evidence that Sauropodomorpha was not the sister group to Theropoda, and instead that theropods and ornithischians were clsoer to each other than either was to sauropodomorphs. Their analysis had a greater sample of early dinosaurs and dinosauromorphs than previous ones. The resurrected an old name, Ornithoscelida ("bird legs"), for the clade comprised of Megalosaurus, Iguanodon, and all taxa closer to them than to Sauropodomorpha. Ornithoscelida is supported by numerous (if sometimes subtle) traits of the skull, vertebrae, humerus, and hindlimb. Among these are:

Simplified cladogram of Dinosauria, under the Ornithoscelida Model

At present whether the Saurischia or Ornithoscelida model (or a third alternative: see the box below!) is correct is not certain. Indeed, a recent analysis showed that these alternatives have just about the same amount of statistical support at the moment. This is an area of of very active research, so future classes of GEOL 104 might come down firmly in support of Saurischia or Ornithoscelida (or Phytodinosauria, I suppose, but personally I think that is the weakest of the three models). At present we'll regard Saurischia as the most likely, but keep in mind it may yet fall to Ornithoscelida.

Yet Another Alternative Dinosauria Arrangement: Phytodinosauria: As they used to say in the old commercials, "but wait, there's more!" Back in the 1980s a possible phylogenetic hypothesis put forth by several researchers was the union of Sauropodomorpha and Ornithischia to the exclusion of Theropoda. This was given the alternative names "Ornithischiformes" or (more commonly) "Phytodinosauria" ("plant [eating] dinosaurs"). This hypothesis is based on the shared presence of phyllodont dentition and several other skull features (including a possible cheeks and beaks), associated with herbivory. A working definition for the clade would be "Diplodocus, Iguanodon, and all taxa sharing a more recent common ancestor with them than with Megalosaurus." No recent computer-generated phylogenetic analysis has supported this model directly, but statistical study shows that it is not much weaker an hypothesis than the other two. In fact, possible support for this arrangement may exist in the enigmatic Chilesaurus (more about it below). In one possible variation of this hypothesis, animals currently considered basal sauropodomorphs may actually be ancestral to ornithischians, explaining the apparent absence of bird-hipped dinosaurs in the Triassic.

Chilesaurus's Relationship Status: It's Complicated: In 2015 a new dinosaur from the Late Jurassic of Chile was described. Several individuals had been found, both juveniles and adults up to 3.2 m long. Given the name Chilesaurus, this dinosaur has a suite of traits associated with different dinosaur clades. Its short skull and long neck resemble those of basal sauropodomorphs; its backwards-pointing pubis and possible beak at the end of the dentary are similar to those of ornithischians; and various vertebral, scapular, pelvic, and hindlimb traits are comparable to theropods (and especially primitive tetanurines.) Its teeth are blunt and have fine denticles, strongly suggesting a herbivorous diet: however, they do not resemble the teeth of either basal sauropodomorphs or ornithischians. The initial analysis found little Chilesaurus to be a bizarre herbivorous tetanurine theropod; alternatively, a paper in August 2017 found it to be the most primitive ornithischian (branching off before the origin of the predentary). Just throwing this out there: it would also make a great amount of sense as a basal ornithischian derived from sauropodomorph-like ancestors under the "Phytodinosauria" hypothesis. Given its position in time, either of these latter ideas require it to be a late survivor retaining the attributes of much older Triassic ancestors. In any case, an earlier representative of the Chilesaurus-lineage would be very helpful in pinning down its place in the (already destabilized) dinosaur family tree.

As you might notice from the discussion above, our knowledge of the basal relationships among dinosaurs is somewhat destabilized at present. One consequence of this is that a number of Triassic taxa cannot at present be securely placed in any of the three major clades. These include:

When our knowledge of the basal relationships within Dinosauria are better established, the positions of these Triassic basal saurischians (probably) should settle down.

>