Key Points:

•Taxonomy (biological nomenclature) is a way of having a universal set of names for groups of living things.

•A formal set of rules exists for naming and organizing taxa (named groups of organisms). Among these are that taxa are named in Latin (or at least in Latinate style) and that they are organized as a nested hierarchy.

•Species represent a fundamental unit in taxonomy. Species are grouped into genera.

•There is no single universally recognized method of identifying when two individuals are in the same species This is even more problematic for fossils, where some relevant information (such as interbreeding, DNA, and so on) is not available.

•Taxonomic differences are not the only reason that two individuals might be different: ontogenetic, sexual, geographic & individual variations have to be considered as well.

TAXONOMY

Taxon (pl. taxa): a named group of organisms.

Traditionally, each culture had its own name for the animals, plants, and other organisms in their region. But EACH culture had its own set of names, so the same type of animal might have many different names. During the 1600s and 1700s, methods were proposed for a formal scientific set of names.

Carlos Linnaeus developed a universal set of rules in the Systema Naturae ("System of Nature") in 1758; later workers added and modified the system (primarily with the addition of new "ranks").

Some of the Linnaean rules:

Linnaean taxonomy has its own special set of grammatical rules:

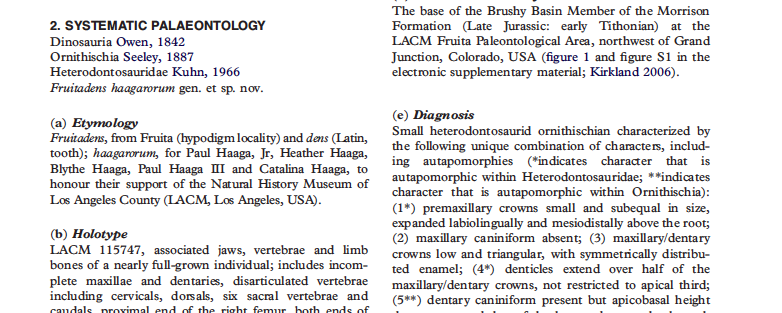

Type Specimens and Type Species: Another aspect of Linnaean taxonomy is that each species must have a particular type specimen. This is a particular individual preserved specimen (extant animal) or fossil (extinct animal) that is the "name holder" for that species. A type specimen is specifically referred to in the original description and diagnosis of the species. It need not be the most complete specimen known at the time (although that helps, as the more complete it is, the better the chance a less-complete individual can be compared to it!). The type specimen plus all the additional (referred specimens) are collectively called the hypodigm. Ultimately, if a species is regarded as being "valid" (that is, representing a real species in Nature), the type specimen is the only individual that is absolutely certain to belong that that species.

Similarly, each genus has a particular type species. This is the particular species to which the genus name is linked. If a genus is valid, the type species is the only species that is absolutely guaranteed to be within that genus.

As an example, CM 9380 (in the collections of the Carnegie Museum of Natural History) is the type specimen of Tyrannosaurus rex, and Tyrannosaurus rex is the type species of the genus Tyrannosaurus.

Because there is disagreement about the features used to define a particular species or genus, different biologists and paleontologists will sometimes disagree about which specimens belong in a particular species, and which species belong in a particular genus (and so forth).

For those interested in a website concerning some unusual Linnaean species names, click here.

Pronouncing Taxon Names: How should one pronounce a taxon name? Short answer first: it really doesn't matter too much, so long as people know what taxon you are referring to. One reasonable approach is to use the pronunciation preferred by the person who coined the name (if you can find out what that pronunciation is) or at least preferred by the specialists in that taxon (if there is a consensus; sometimes there is, sometimes there isn't).

If you want something more rigorous, one preference is to use late northern Continental Latin pronunciation. This is the language of Kepler, Copernicus, and (most importantly) Linnaeus. Alternatively, you might consult this site for suggestions. (There are some differences between these: in the former "-idae" the vowel at the end is like the "a" in "plate"; in the latter it is like the "e" in "we".) In any case, please do NOT use either Church Latin or Classical Latin: those pronunciations represent language forms many centuries before the rise of scientific Latin.

Linnaeus' "species" were taxa like lions, tigers, black bears, etc. These were assemblages of individuals that share certain attributes:

Darwin did not regard species as a distinct "kind" of biological entity. Instead, he considered them as essentially the same thing as geographic or stratigraphic variations (see these below), but ones in which extinction has removed the intermediate forms that otherwise would blend into the closest living relative group.

20th Century biologist Ernst Mayr (and most contemporary biologists) formalized their definition of a species as a "naturally occurring populations that interbreed and produce viable fertile offspring".

But there are some problems with this. For one: hybrids (crosses between two separate species) do occur naturally, and many of these are actually fertile! And for paleontologists: we can't test interfertility between populations because they are dead!

So we are stuck looking only at shapes (and in fact, only the shapes of those hard parts that survive fossilization).

The question then becomes: how different do two individuals, or two populations, have to be for us to consider them different species? This is actually a terribly difficult question even with living organisms!! There are several sources of variation:

To Next Lecture.

To Previous Lecture.

To Lecture Schedule.