The Reptilian Stem - A Work in Progress

John Merck

Synapsida is only half of Amniota. The other half - "reptiles" - contains living turtles, squamates, Sphenodon, crocodylians, and birds, and their fossil relatives. Traditionally, and for most of the age of cladistics, most of its diversity was taken up by Diapsida, characterized by creatures with classic diapsid temporal fenestration or its derivatives. But things have changed. Alas, we have no consensus on:

- The exact shape of its cladogram

- Exactly who is a member

- Proper taxonomic nomenclature for this part of the tree, especially its more basal part.

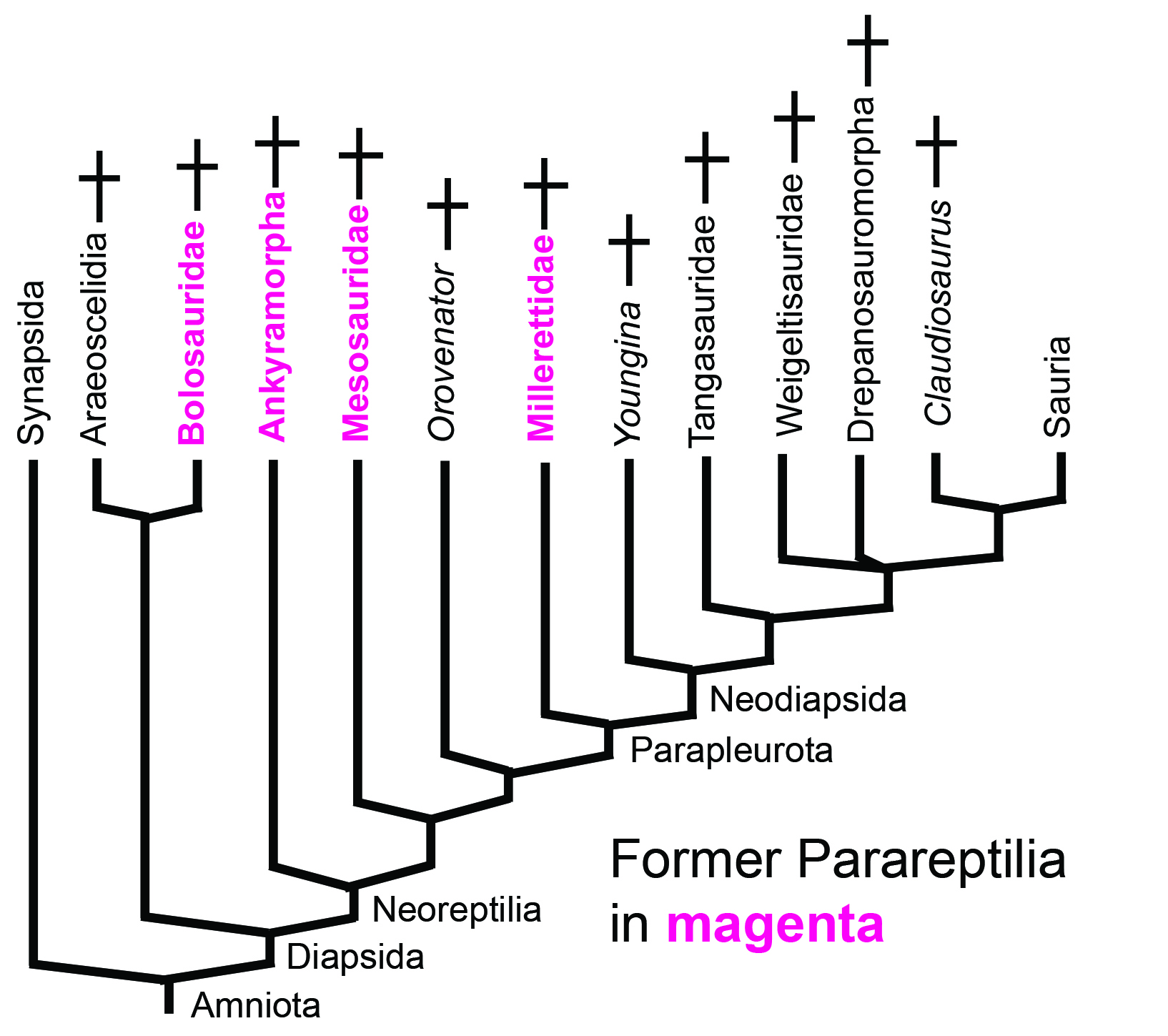

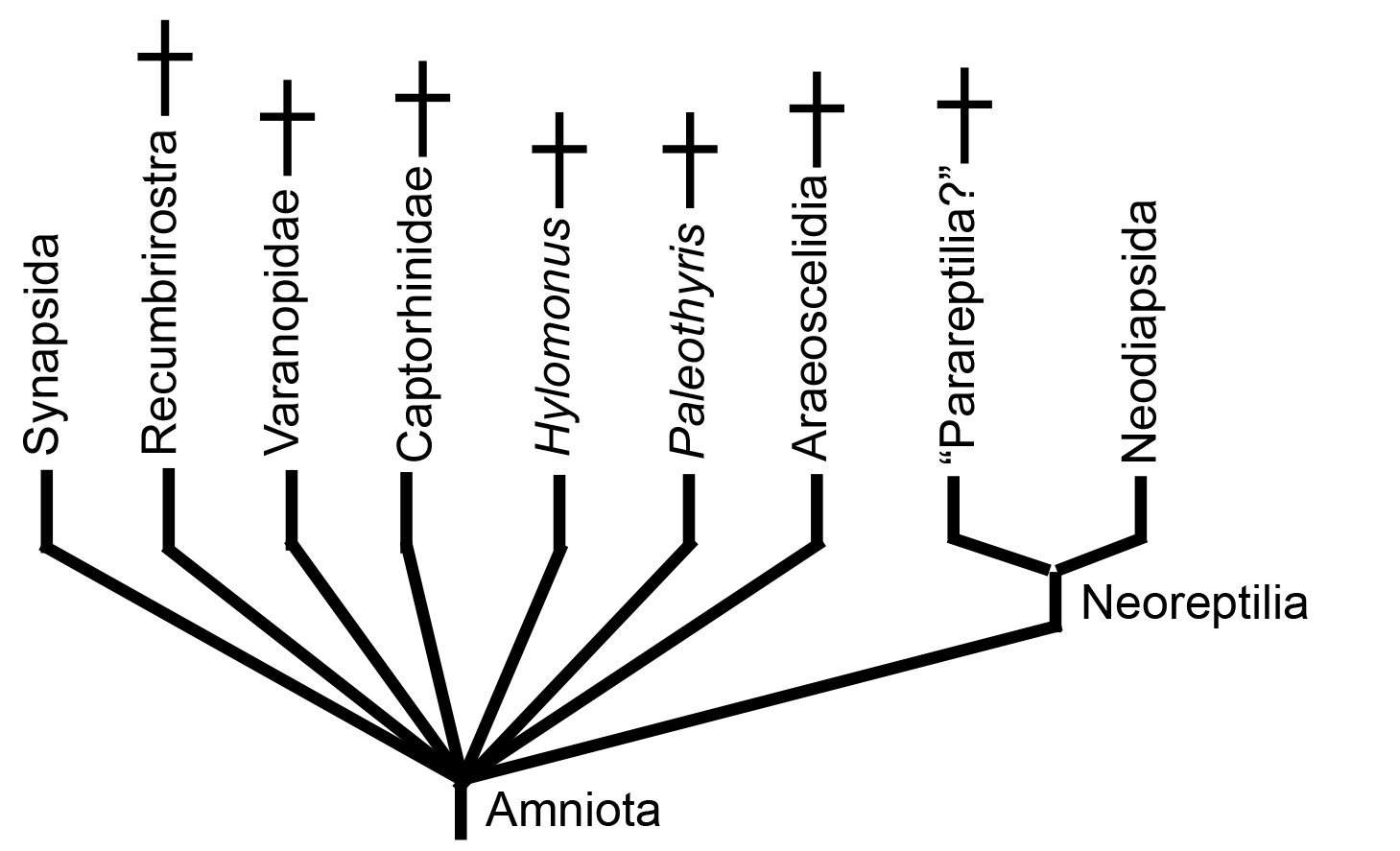

An honest strict consensus of 21st century research .

The last decade has seen no consensus. Consequently the 2023 strict consensus cladogram above is actually less resolved than our naive view from 2015. And yet it is not so bad. By definition, amniotes belong to one of two total-group clades:

- Synapsida

- Sauropsida (as the term has come to be used.)

What has changed since 2023:

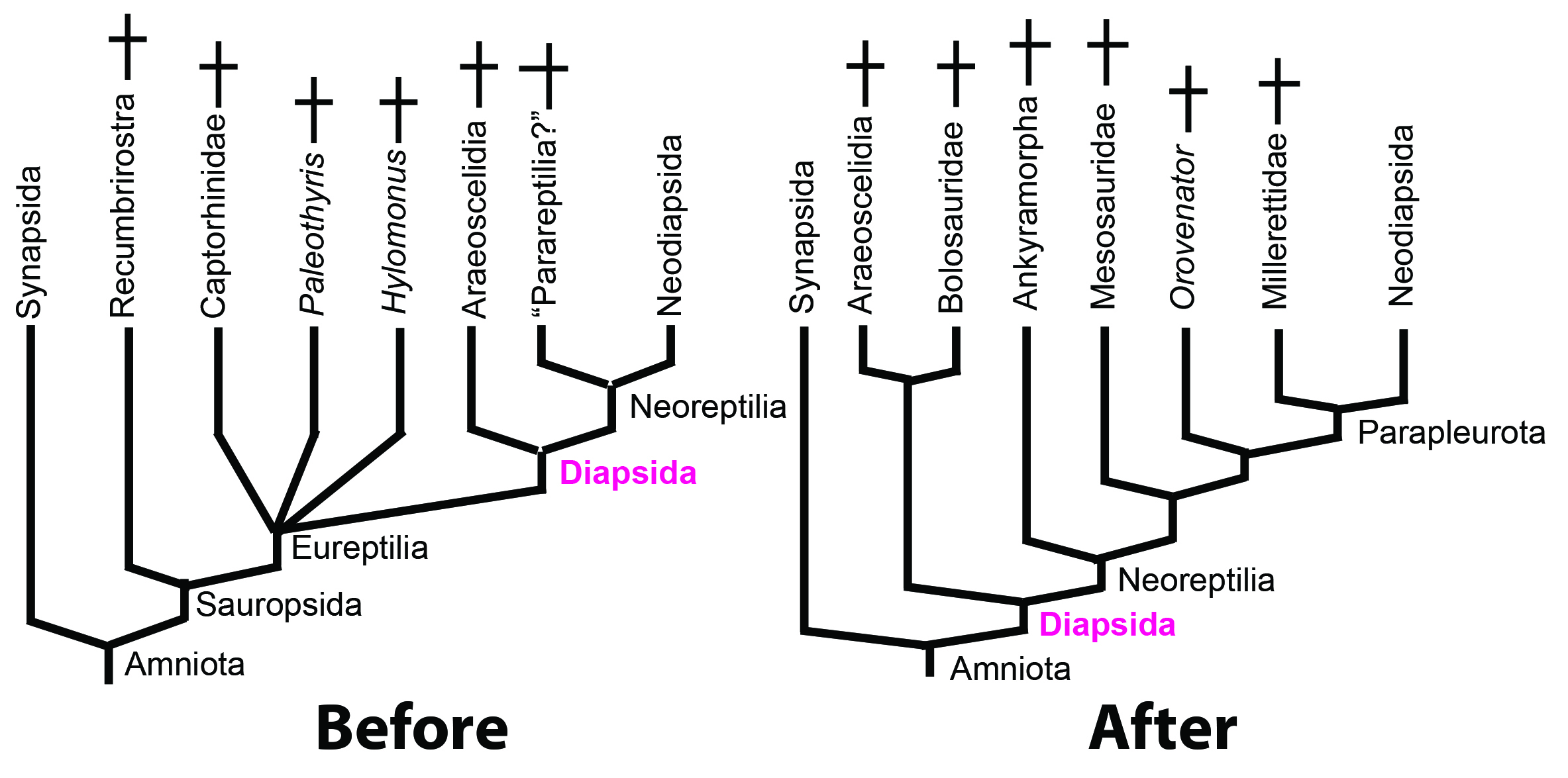

- Parareptilia - the repository for many Paleozoic sauropods since the early days of cladistics (see may Gauthier et al., 1988) has been challenged as paraphyletic (Ford and Benson, 2019), supported as monophyletic (Simões et al., 2022) but in the "last word" for this semester by Jenkins et al., in press. finds them to be polyphyletic. (Yikes!)

- Captorhinidae, Hylomonus, and Paleothyris - long regarded as stem sauropsids - have been recovered by several research groups as (Simões et al., 2022, Jenkins et al., in press.) as stem amniotes!

- Even more disruptively, Simões et al., 2022 recover Araeoscelidia as stem amniotes! Especially problematic as these are the earliest creatures to display classic diapsid fenestration. Most cladistics definitions of Diapsida are hung off of them. More recently, Jenkins et al., 2025 restore them to Sauropsida.

Reptilia or Sauropsida?

Both terms have been used for the sister-taxon of Synapsida and neither has a "clean title" to the clade because of issues that haunt us from the early, revolutionary days of cladistics when:- Systematists were overconfident in the permanence of the phylogenetic hypotheses they developed

- And did not feel obliged to respect rules of priority

-

"The most recent common ancestor of extant turtles and saurians, and all its descendents."

AKA: Min ∇ (Testudines, Sauria)

Given Gauthier et al.'s convictions that:

- Turtles belonged in Parareptilia

- Saurians belonged in Diapsida

Sauropsida is defined by Laurin and Reisz, 1995 as:

-

"The last common ancestor of mesosaurs, testudines and diapsids, and all its descendents."

AKA: Min ∇ (Mesosaurus, Testudines, Diapsida)

This anchors the definition on Mesosauridae - a basal group never appearing on the synapsid side. But alas:

- Ford and Benson place Mesosauridae, along with other members of Parareptilia, far up the tree

- Simões et al. move Araeoscelidia - classic "diapsids" outside Amniota. All of which makes Laurin and Reisz' definition useless to us as well.

So we punt!

In common usage, "Sauropsida" has come to be treated as the total-group sister-taxon of Synapsida. This is a cultural response to a need that is useful, even if it doesn't respect priority. For now and until a proper definition appears, we use this name that is at least free of cultural association with traditional definitions of "reptiles." (We address the issue of turtles in a later lecture.) Live with it.

Diapsida

What has changed since GEOL431 - 2023.

Diapsids are among the first amniotes of the Late Carboniferous, however during the Paleozoic they were a minor component of the terrestrial fauna. That changed during the Mesozoic, when they achieved ecological dominance. Modern diapsids include :

- Birds

- Crocodylians

- Squamates (lizards and snakes)

- Sphenodon, the New Zealand tuatara.

- Suborbital opening in the palate appears as a broad suborbital fenestra.

- Limbs long and slender, emphasizing zeugopodium and autopodium. Typically, radius is at least 70% length of humerus. (Compare Claudiosaurus with non-diapsid Captorhinus.)

- Complex joint between tibia and astragalus that creates a relatively solid immobile articulation between the two. (In extreme cases, as with birds, these elements fuse into a tibiotarsus.)

- Metatarsal IV at least twice the length of metatarsal I. (Link to pes of Petrolacosaurus.)

One feature commonly associated with Diapsida but absent from our list is the supratemporal fenestra. According to Jenkins et al., in press., this feature has arisen at least three times independently in Diapsida, first in Araeoscelidia.

There are two general patterns here:

- The jaws are long and slender, and the leverage of their adductor muscles limited by the shortening of the temporal region, resulting in a quick but weak bite, suitable for hunting the insects that were diversifying during the Carboniferous.

Arguably connected with the presence of temporal fenestrae. Abel et al., 2022 used Captorhinus to model the distribution of stress generated by biting across the elements of the skull roof. Their model identifies the location of the infratemporal and supratemporal fenestra as zones of weakness where there may be selective pressure not to deposit bone. - Lengthening of the limbs (especially of the distal elements) suggest adaptations for faster locomotion.

- Sauria: The crown-group of living diapsids - the last common ancestors of lizards and birds and all of its descendants will be covered later

Petrolacosaurus kansensis

Araeoscelidia: (Late Carboniferous - Early Permian). Recognize since the beginnings of cladistics as the basal clade of Diapsida, including Late Carboniferous Petrolacosaurus - the oldest known sauropsid. Small slender animals characterized by:

- Relatively long neck and cervical series (eight cervical vertebrate).

- Long slender limbs

Araeoscelidians are specialized either as arboreal or aquatic animals. Remarkable more for their plesiomorphies, including retention of:

- caniniform teeth

- a lacrimal that extends, unrestricted, to the naris

- the postsplenial of the jaw

- the posterior coracoid

- the cleithrum

Parareptilia - in memorium:

Before proceeding, let's pause to note the passing of Parareptilia - a proposed clade originally anchored on turtles (Gauthier et al., 1988) but containing many Paleozoic sauropsids. Now dispersed across the saurian stem. Will it rise from the grave in later analyses? GORK. But it's labile history certainly does not inspire confidence.

Let's look at its constituents.

Synapomorphies:

- Teeth with cusps and ridges

- Extremely tall coronoid process

- The transverse flange of the pterygoid and ectopterygoid form a load-bearing buttress against the medial surface of the maxilla.

Bolosauridae contains the earliest known facultative biped - Eudibamus cursorius. Eudibamus was redescribed by Berman et al., 2021 as actually being capable of moving its limbs in an upright "parasagittal" digitigrade posture, a definite first for the Early Permian.

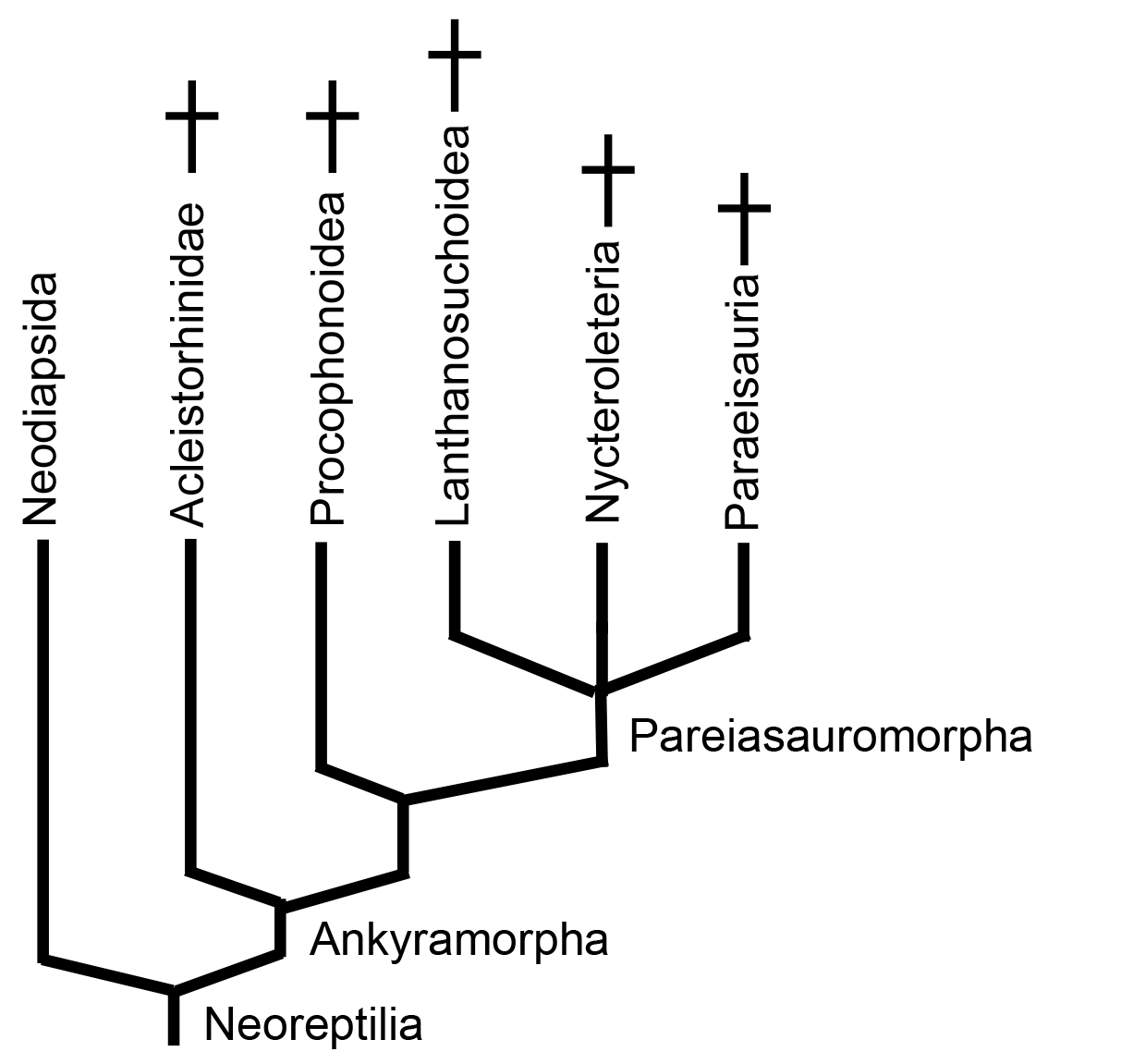

Neoreptilia

(Early Permian - recent)

Min ∇ (Ankyramorpha, Sauria).

Synapomorphies:

- Lacrimal excluded from margin of naris

- Caniniform teeth (synapomorphy of Amniota + Protorothyrididae) are lost

Ankyramorpha

Previously the monophyletic core of "Parareptilia," this clade encompasses important land animals of the Early Permian to Triassic, some of whom were conspicuous parts of land fauna in the Permian. Our cladogram is informed by Jenkins et al., in press. for the position and overall structure of Ankyramorpha, and by Cisneros et al., 2021 for internal details.

Ankyramorphs are comprised of creatures with relatively short but broad heads whose dermal bones show various degrees of ornamentation. Synapomorphies include:

- anterodorsal process of maxilla high and extending to the dorsal limit of the external naris

- posterior process of postorbital nearly as wide as long

- heavily sculptured dermal bones of skull roof

- ectopterygoid contributes to outer-most border of transverse flange of palate if present (See Lanthanosuchus)

- parasphenoid rostrum shorter than body

- paroccipital process antero-posteriorly expanded

- Surangular and prearticular short - do not extend anterior to coronoid process (See Owenetta.)

- Anchor-shaped interclavicle.

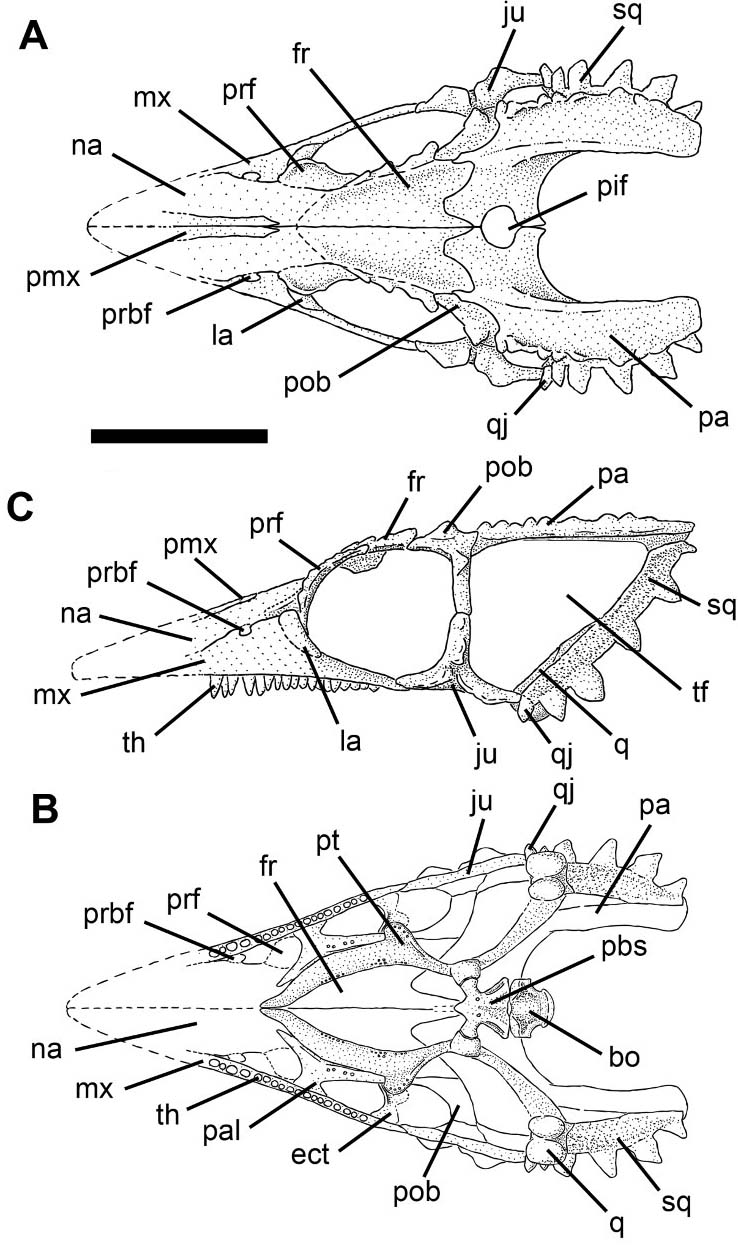

Acleistorhinidae: (Early Permian) Small (20 - 40 cm.) probably ecological generalists with simple peg-like teeth and short deep skulls (right). Acleistorhinus, itself, is the oldest known ankyramorph. The only other acleistorhinid, Colobomycter is known only from a cranium that sports elongate premaxillary teeth. Synapomorphies:

- Elongate basipterygoid process

Procolophonoidea: (Late Permian - Late Triassic) Small (20 - 40 cm.) probably ecological generalists to herbivores with bulbous blunt teeth. Typically stocky with short tails, Many members sport cranial ornamentation and armor of dermal scutes. Contains:

- Owenettidae: (Late Permian). (Link to Owenetta) Relatively plesiomorphic, but distinguished by the presence of an infra temporal embayment rather than a fully enclosed fenestra - a derived feature that we will see independently derived in many other sauropsids.

- Procolophonidae: (Late Permian - Late Triassic).

- Naris circular or dorsoventrally expanded

- Maxillary depression present (cheeks?)

- Three - four premaxillary teeth

- Maxillary teeth with transversely expanded bases

- Ten - twelve maxillary teeth

Pareiasauromorpha

The "crown" of the ankyramorph tree contains three disparate groups from the Permian.

Lanthanosuchoidea: (Early - Late Permian) Small (20 - 40 cm.) with flat, heavily sculpted skulls. (E.G. Lanthanosuchus right.) Probably ecological generalists with simple peg-like teeth.

The infra temporal fenestra remains large.

Nycteroleteridae: (Middle Permian - Late Permian) Small (20 - 40 cm.) Mostly known from skulls, however Emeroleter shows a large skull on a relatively gracile bodies and limbs. These include the ankyramorphs with the most extensive embayments of the posterior cheek margin and small slender stapes - strongly indicative of impedance-matching ears. Their phylogeny is poorly resolved but Tsuji et al. 2012 find Macroleter to be the most basal. This tracks with its retention of a small infra temporal fenestra, otherwise absent in this group.

Synapomorphies:

- distinct emargination at the posterolateral edge of the skull concave

- smooth depression in the temporal region extending across most of the squamosal and large parts of the quadratojugal

- remaining area of the temporal region is characterized by distinctive dermal sculpturing

- a well developed, laterally protruding rim at its dorsal margin of the otic notch formed by the overhanging supratemporal and postorbital.

General trends:

- Proportions: Medium to large herbivorous reptiles. Short, deep and wide bodies, presumably with large digestive systems. Probably similar ecologically and metabolically to living giant tortoises.

- Skull: Short and wide, characterized by flaring armored cheeks, bumps and horns. E.G.: Bunostegos. There is no temporal fenestration or anything analogous to it.

- Teeth: Teeth are phyllodont, similar to those of large herbivorous iguanas.

- Armor: Pareiasaurs have extensive dermal armor. In some, the armor is interlocking.

Synapomorphies:

- A ventral flange of the quadratojugal

- A posterior extension of the squamosal that covers the area occupied by the quadrate emargination in other parareptiles.

- A large boss on the supratemporal

- A large ventral process on the angular.

Mesosauridae: (Early Permian) Mesosaurus, Braziliosaurus, and Stereosternum. Inhabiting the incipient basin of the South Atlantic, their fossils are from southern South America and Africa. Mesosaur distribution was among the data of Alfred Wegener supporting continental motion. The first amniotes with clear adaptations to aquatic life. Known from many well-preserved specimens, yet phylogenetically enigmatic. Mesosaurs are known from good growth series, with adults typically approaching 35 cm in snout-vent length, however larger specimens with overall length of 2.5 m are known. (Piñeiro et al., 2025)

Characteristics:

- Broad, paddle-shaped limbs adapted for swimming.

- Blade of scapula shortened, as often seen in secondarily aquatic tetrapods

- Ribs pachyostotic thickened with dense bone tissue acting as ballast

- A "snout-hunter" - Elongate rostrum with long slender teeth for capturing prey with rapid sideways motion of head. (Living analogs include: gars, gavials).

- Viviparity: Piñeiro et al., 2012b report the presence of late stage embryos in the abdominal cavities of mesosaurs. Viviparity is a common adaptation to marine life in amniotes.

Mesosaur issues:

- Caudal autotomy: MacDougal et al., 2020 report planes of caudal autotomy in the mesosaur Stereosternum but speculate that they represent a seldom-used plesiomorphy, as other aspects of the anatomy, including webbed limbs, indicate an aquatic life style for which an intact tail would have been important. We have seen evidence of caudal autotomy as far down as captorhinids (leBlanc et al., 2018.), so not implausible.

- For a century, the presence or absence of an infratemporal fenestra has been debated. Piñeiro et al., 2012 seems to have resolved this in favor of its being present. Whether this autapomorphic or characteristic of a larger group (possibly even Amniota) depends on the resolution of...

- The phylogenetic position of mesosaurs, which have been regarded as:

- Basal members of Parareptilia (Gauthier et al., 1988)

- Stem sauropsids (Laurin and Reisz, 1995)

- Stem amniotes (Hill, 2005)

Moving upward,

Orovenator mayor: (Early Permian). Known only form the anterior skull of a single specimen with diapsid fenestration - a second origin of the supratemporal fenestra (Jenkins et al., in press.).

Unremarkable except that the overall skull shape - with a long snout and slender temporal bars separating fenestrae begin more closely to resemble what we see in creatures farther up the tree.

Parapleurota

New for 2025, Jenkins et al., in press. recover a significant new diapsid clade - Parapleurota (Middle Permian to Rec.)Its diversity:

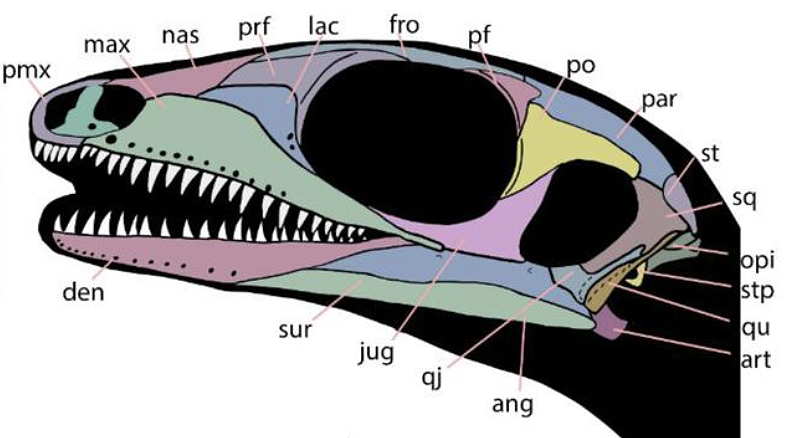

- Millerettidae: Another ex-parareptile, previously regarded as a basal parareptile despite its relatively young age, invoking an awkward ghost lineage. (Ford and Benson, 2019. Now bumped up the tree into a more stratigraphically congruent position.

- Neodiapsida: Includes Sauria - the diapsid crown group, and its closest relatives, among whom the classic diapsid condition stabilizes.

Synapomorphies primarily pertain to evolution of the impedance-matching ear.

- Dorsal process of the stapes absent. This frees the stapes from its role as a structural component, repurposing it exclusively for conducting sound.

- Embayment for a tympanum formed by the squamosal, quadratojugal, and quadrate.

- Lower infratemporal bar is absent, causing infratemporal fenestra to appear as a broad open embayment

Small (20 - 40 cm.) probably ecological generalists with simple peg-like teeth. Their synapomorphies are highly technical. But note:

- Phylogenetically basal forms like Lanthanolania have open infra temporal embayments. But this is reduced in more derived forms, yielding a reversal to an enclosed fenestra in Milleretta.

- No millerettid for whom the temporal skull roof is preserved shows a supratemporal fenestra, however Milleretta's parietal is laterally expanded in a way that suggests that it may be present in young but is closed developmentally.

Synapomorphies:

- Descending flange of parietal adjacent to supratemporal fenestra, resulting in adductor muscles originating, in part, from dorsal surface of parietal.

- Postfrontal participates in margin of supratemporal fenestra.

- Quadrate is exposed laterally by reduction of squamosal and quadratojugal

- Parasphenoid teeth reduced or absent

- Femur is slender and sigmoid

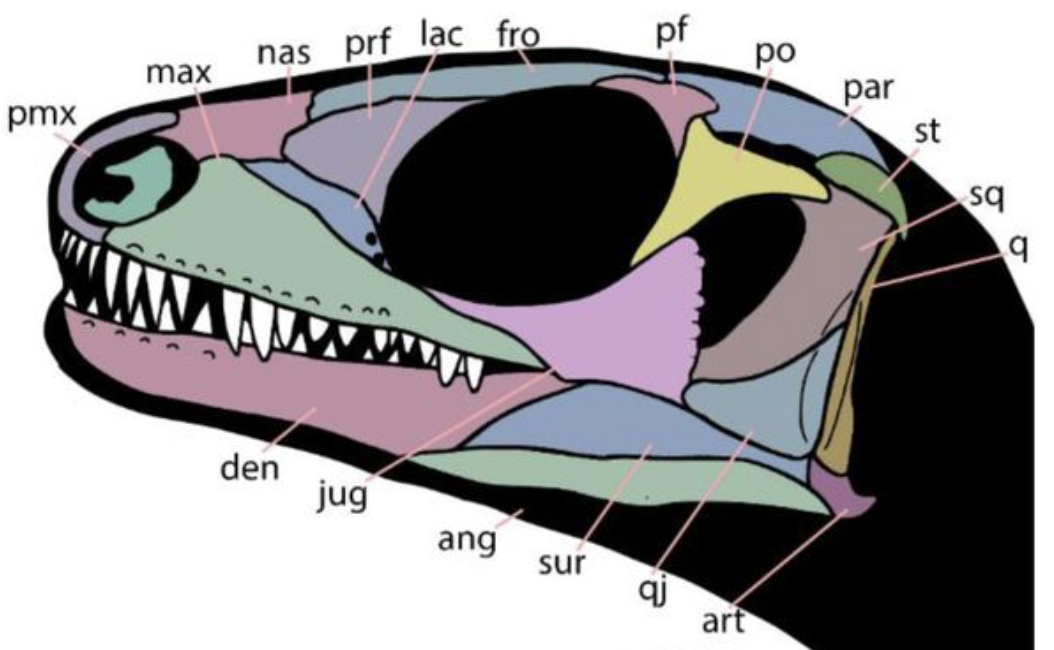

"Younginiformes" (Late Permian - Early Triassic) Considered a clade during the 20th century (Gauthier et al., 1988), this "group" has emerged as a grade of basal neodiapsids in 21st century analyses, such as Hunt et al., 2023's description of CT scans of Youngina. This grade group encompasses fully terrestrial members (Youngina) and semiaquatic ones (Hovasaurus) Their skulls are relatively uniform, with longish low snouts and homodont dentition.

- In Youngina (right), the infratemporal fenestra is fully enclosed - a reversal.

- In Acerosodontosaurus, it is open ventrally (plesiomorphic)

Some "younginiforms" form a clade - Tangasauridae whose members show evidence of semi-aquatic adaptations, best seen in Hovasaurus.

- Megalancosaurus (Late Triassic - right) Link to reconstruction. With:

- prehensile tail

- opposable digits on manus and pes

- long neck

- barrel chested with ribs fused to vertebrae

- thoracic vertebrae fused into notarium

- pointed snout

- Drepanosaurus (Late Triassic) Link to description. Like a large, headless Megalancosaurus, but with strangely developed forelimbs.

- Avicranium (Late Triassic) The best known drepanosaurid cranium, described by Pritchard and Nesbitt, 2017 reveals that for all its outward similarity to a bird's, it's skull lacked saurian features like an embayment for a tympanum.

- Megalancosaurus preonensis (pictured) has a robust hindlimb and clawless opposable hallux indicative of prehensile climbing on narrow branches

- Megalancosaurus edennae's hallux is not opposable and all digits have long slender claws, suggesting that they climbed on larger supports.

Wiegeltisauridae: (Late Permian - Early Triassic) The first gliders, employing a patagium supported by dermal elements of the trunk. Also the earliest obligate amniote arborealists.

- Coelurosauravus (Late Permian)Ornate triangular head with "casque" resulting from enlargement of the infratemporal fenestra. Most recently redescribed by Buffa et al., 2021.

A gliding membrane supported on elongate dermal "palatial" elements that are not ribs (in contrast to the extant gliding squamate Draco Volans.) Buffa et al., 2022 propose that these could be elongate versions of lateral gastralia, as they appear to be continuous with the gastralia and originate low on the trunk. They also note that, like Draco, Coelurosauravus could have grabbed the leading edge of of its patagium with its manus to stabilize it.

- Possibly related, Longisquama (Middle-Late Triassic) Triangular head and elongate plume-like display (?) structures.

Phylogeny: The more derived stem saurians display considerable convergence on other forms, leading to a diverse range of phylogeny hypotheses. Some highlights:

- Senter, 2004 found drepanosaurids and wiegeltisaurids to form a monophyletic group that he called Avicephala.

- More recently, Renesto et al. 2010 and Buffa et al. 2024 found Avicephala to be polyphyletic, with the drepanosaurids as members of sauria.

- With the benefit of Avicranium, Pritchard and Nesbitt, 2017 and Pritchard et al., 2021 confirmed the monophyly of Avicephala. The polytomy we present here is, therfore a consensus.

Claudiosaurus: The lower temporal bar is definitely incomplete in Claudiosaurus (right). In life, its place would be occupied by an unossified ligament. Various diapsids would eventually reossify that ligament in various ways, but from this point forward, we deal with diapsids who are descended from creatures whose infratemporal fenestrae have been transformed to broad embayments in the lower margin of their cheeks.

Claudiosaurus was a limb-propelled swimmer with a relatively long neck. When first described it was called a "plesiosaur ancestor." That's probably wrong, but it demonstrates that even in the Permian, diapsids displayed a tendency opportunistically to evolve aquatic forms. Claudiosaurus was fresh-water aquatic, however, not marine.

Sauria:

(Late Permian - Rec.) Min ∇ (Lepidosauria, Archosauria)Here, for once, in a pleasing cladogram is the arrangement of Gauthier, 1984, in which two crown-groups were recognized in Sauria:

- Archosauria: Min ∇ (Crocodylia, Aves)

- Lepidosauria: Min ∇ (Squamata, Sphenodon)

- Archosauromorpha: Max ∇ (Archosauria ~ Lepidosauria)

- Lepidosauromorpha: Max ∇ (Lepidosauria ~ Archosauria)

- Of the skull:

- Prominent retroarticular projection of jaw: An extension to the jaw that projects behind the jaw joint.

- The paroccipital process of the opisthotic firmly sutured to the skull roof.

- Of the appendicular skeleton:

- The cleithrum is lost.

- The fifth distal tarsal is lost.

- The fifth metatarsal is hooked.

Stay tuned.

Additional reading:

- Pascal Abel, Yannick Pommery, David Paul Ford, Daisuke Koyabu, and Ingmar Werneburg, 2022. Skull Sutures and Cranial Mechanics in the Permian Reptile Captorhinus aguti and the Evolution of the Temporal Region in Early Amniotes. Frontiers in Ecology Evolution, Sec. Paleontology Volume 10 - 2022.

- Michael Benton, 1985. Classification and phylogeny of the diapsid reptiles. Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society 84, 97-164.

- Julien Benoit, David P. Ford, Juri A. Miyamae, and Irina Ruf, 2021. Can maxillary canal morphology inform varanopid phylogenetic affinities?. Acta Paleontological Polonica 66(2) 389-393.

- David Berman, Robert Reisz, Diane Scott, Amy Henrici, Stuart Sumida, and Thomas Martens, 2000. Early Permian bipedal reptile. Science. 290 (5493). 969-972.

- David S Berman, Stuart S. Sumida, Amy C. Henrici, Diane Scott, Robert R. Reisz, and Thomas Martens, 2021. The Early Permian Bolosaurid Eudibamus cursoris: Earliest Reptile to Combine Parasagittal Stride and Digitigrade Posture During Quadrupedal and Bipedal Locomotion. Frontiers in Ecology and Evolution, Volume 9 - 2021

- Valentin Buffa, Eberhard Frey, Sebastien Steyer, and Michel Laurin, 2021. A new cranial reconstruction of Coelurosauravus elivensis Piveteau, 1926 (Diapsida, Weigeltisauridae) and its implications on the paleoecology of the first gliding vertebrates. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology, Volume 41(2) - 2021.

- Valentin Buffa, Eberhard Frey, Sebastien Steyer, and Michel Laurin, 2022. The postcranial skeleton of the gliding reptile Coelurosauravus elivensis Piveteau, 1926 (Diapsida, Weigeltisauridae) from the late Permian of Madagascar. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology, Volume 42(1) - 2022.

- Valentin Buffa, Eberhard Frey, J-Sebastien Steyer, Michel Laurin, 2024. ‘Birds’ of two feathers: Avicranium renestoi and the paraphyly of bird-headed reptiles (Diapsida: ‘Avicephala’). Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society, 202(4).

- Robert Carroll, 2009. The Rise of Amphibians: 365 Million Years of Evolution. Johns Hopkins University Press, Baltimore. 360 pp.

- Cisneros, J. C., Kammerer, C. F., Angielczyk, K. D., Fröbisch, J., Marsicano, C., Smith, R. M. H., & Richter, M. (2020). A new reptile from the lower Permian of Brazil (Karutia fortunata gen. et sp. nov.) and the interrelationships of Parareptilia. Journal of Systematic Palaeontology, 18(23), 1939–1959. https://doi-org.proxy-um.researchport.umd.edu/10.1080/14772019.2020.1863487

- Susan Evans, 1980. The skull of a new eosuchian reptile from the Lower Jurassic of South Wales. Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society 70: 203–264.

- Susan Evans, 1991. A new lizard-like reptile (Diapsida: Lepidosauromorpha) from the Middle Jurassic of England. Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society 103(4) 391–412.

- David P. Ford and Roger B. J. Benson , 2018. A redescription of Orovenator mayor. Using high-resolution μCT, and the consequences for early amniote phylogeny Papers in Paleontology, 5(2), 197-239

- David P. Ford and Roger B. J. Benson , 2019. The phylogeny of early amniotes and the affinities of Parareptilia and Varanopidae. Nature Ecology & Evolution volume 4, pages57–65

- Jacques Gauthier, 1984. A cladistic analysis of the higher systematic categories of the Diapsida. [PhD dissertation]. Available from University Microfilms International, Ann Arbor, #85-12825, vii + 564 pp.

- Jacques Gauthier, Arnold Kluge, and Timothy Rowe, 1988. The early evolution of the Amniota. In: M. Benton Ed. The phylogeny and classification of tetrapods, Vol I: Amphibians, reptiles, birds. Clarendon Press, Oxford. Pp. 103-155.

- Gow, C. E. 1975. The morphology and relationships of Youngina capensis Broom and Prolacerta broomi Parrington. Palaeontologia Africana, 18, 89–131.

- Robert Hill, 2005. Integration of Morphological Data Sets for Phylogenetic Analysis of Amniota: The Importance of Integumentary Characters and Increased Taxonomic Sampling. Systematic Biology. 54(4): 530-547.

- Annabel K. Hunt, David P. Ford, Vincent Fernandez, Jonah N. Choiniere, Roger B. J. Benson. 2023. A description of the palate and mandible of Youngina capensis (Sauropsida, Diapsida) based on synchrotron tomography, and the phylogenetic implications. Papers in Palaeontology. 9:5.

- Xavier A. Jenkins, Adam C. Pritchard, Adam D. Marsh, Ben T. Kligman, Christian A. Sidor, and Kaye E. Reeds. 2020. Using manual unfurl morphology to predict substrate use in the Drepanosauromorpha and the description of a new species. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 40:5, e1810058.

- Kelsey M. Jenkins, William Foster, James G. Napoli, Dalton L. Meyer, Gabriel S. Bever, Bhart-Anjan S. Bhullar, 2024. Cranial anatomy and phylogenetic affinities of Bolosaurus major, with new information on the unique bolosaurid feeding apparatus and evolution of the impedance-matching ear. The Anatomical Record July 2024.

- Xavier A. Jenkins, Roger B. J. Benson, David P. Ford, Claire Browning, Vincent Fernandez, Kathleen Dollman, Timothy Gomes, Elizabeth Griffiths, Jonah N. Choiniere, Brandon R. Peecook, In press. Stepwise Assembly Of Crown Reptile Anatomy Clarified By Late Paleozoic Outgroups Of Neodiapsida. Bioarchive doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2024.11.25.625221.

- Xavier A. Jenkins, Hans-Dieter Sues, Savannah Webb, Zackary Schepis, Brandon R. Peecook, Arjan Mann, 2025. The recumbirostran Hapsidopareion lepton from the early Permian (Cisuralian: Artinskian) of Oklahoma reassessed using HRμCT, and the placement of Recumbirostra on the amniote stem. Papers in Palaeontology 11(1).

- Michel Laurin and Robert Reisz, 1995. A reevaluation of early amniote phylogeny. Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society. 113:165-223.

- A. R. H. LeBlanc, M. J. MacDougall, Y. Haridy, D. Scott, and R. R. Reisz. 2018. Caudal autotomy as anti-predatory behaviour in Palaeozoic reptiles. Nature, Scientific Reports 8(3328).

- Mark J. MacDougall, Antoine Verrière, Tanja Wintrich, Aaron R. H. LeBlanc, Vincent Fernandez & Jörg Fröbisch . Conflicting evidence for the use of caudal autotomy in mesosaurs. Sci Rep 10, 7184 (2020)

- Arjan Mann, Ami S. Calthorpe, and Hillary C. Maddin, 2021. Joermungandr bolti, an exceptionally preserved ‘microsaur’ from the Mazon Creek Lagerstätte reveals patterns of integumentary evolution in Recumbirostra. Royal Society Open Science 8(7)

- Hillary C. Maddin, Arjan Mann & Brian Hebert, 2020. Varanopid from the Carboniferous of Nova Scotia reveals evidence of parental care in amniotes. Nature Ecology & Evolution volume 4, pages50–56

- Luke E. Meade, Richard J. Butler, Marc E. H. Jones, Nicholas C. Fraser, 2024. A new procolophonid with complex dentition from the Late Triassic of southwest England. Papers in Palaeontology 10(6) e1605

- Sean Modesto and Robert Reisz, 2003. An enigmatic new diapsid reptile from the Upper Permian of Eastern Europe. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 22(4):851-855.

- Sean Modesto and Jason Anderson, 2004. The Phylogenetic Definition of Reptilia. Systematic Biology, 53(5):815-821.

- Graciela Piñeiro, Jorge Ferigolo, Alejandro Ramos, and Michel Laurin, 2012. Cranial morphology of the Early Permian mesosaurid Mesosaurus tenuidens and the evolution of the lower temporal fenestration reassessed. Comptes Rendus Palevol, 11(5), Pp 379-391

- Graciela Piñeiro, Jorge Ferigolo, Melitta Meneghel, and Michel Laurin, 2012. The oldest known amniotic embryos suggest viviparity in mesosaurs. Historical Biology, iFirst 2012, Pp 1-11.

- Graciela Piñeiro, Pablo Nuñez Demarco, and Michel Laurin, 2012. The Largest Mesosaurs Ever Known: Evidence from Scanty Records, Fossil Studies 2025, 3, 1. https://doi.org/10.3390/fossils3010001.

- Adam Pritchard and Sterling Nesbitt, 2017. A bird-like skull in a Triassic diapsid reptile increases heterogeneity of the morphological and phylogenetic radiation of Diapsida. Royal Society Open Science, 4(10): 170499.

- Adam Pritchard, Hans-Dieter Sues, Diane Scott, and Robert Reisz, 2021. Osteology, relationships and functional morphology of Weigeltisaurus jaekeli (Diapsida, Weigeltisauridae) based on a complete skeleton from the Upper Permian Kupferschiefer of Germany. Paleontology and Evolutionary Science, May 20, 2021.

- Robert Reisz, 1981. A diapsid reptile from the Pennsylvanian of Kansas. Special Publication of the Museum of Natural History, University of Kansas 7: 1-74.

- Robert Reisz, Sean Modesto, and Diane Scott. 2011. A new Early Permian reptile and its significance in early diapsid evolution. Proceedings of the Royal Society B 278 (1725): 3731–3737.

- Silvio Renesto, Justin Spielmann, Spencer Lucas, and Giorgio Spagnoli. 2010. The taxonomy and paleobiology of the Late Triassic (Carnian-Norian: Adamanian-Apachean) drepanosaurs (Diapsida: Archosauromorpha: Drepanosauromorpha). New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science Bulletin. 46:1–81.

- Silvio Renesto and Seller. 2023. Differences in the hindlimb anatomy in the two species of the Triassic drepanosauromorpha Megalancosaurus indicate habitat partitioning in the arboreal environment. Rivista Italiana di Paleontologia e Stratigrafia 129(2).

- Phil Senter. 2004. Phylogeny of Drepanosauridae (Reptilia: Diapsida). Journal of Systematic Palaeontology 2 (3): 257-268.

- Matt Szostakiwskyj, Jason D. Pardo, Jason S. Anderson. 2015. Micro-CT Study of Rhynchonkos stovalli (Lepospondyli, Recumbirostra), with Description of Two New Genera. Plos|One June 10, 2015.

- Tiogo Simões, Christian F. Kamerer, Michael Caldwell, and Stephanie Pierce. 2022. Successive climate crises in the deep past drove the early evolution and radiation of reptiles. JScience Advances 8(33). name="tsuji2012">

- Linda Tsuji, Johannes Müller, and Robert Reisz, 2012. Anatomy of Emeroleter levis and the phylogeny of the nycteroleter parareptiles. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 32(1): 45-67.

- Julien Benoit, David P. Ford, Juri A. Miyamae, and Irina Ruf, 2021. Can maxillary canal morphology inform varanopid phylogenetic affinities?. Acta Paleontological Polonica 66(2) 389-393.