Neopterygii - Half of vertebrate diversity in one hour

John Merck

Link to Teleosteomorpha cladogram and phylogram cheat-sheets

Link to Acanthomorpha cladogram and phylogram cheat-sheets

Neopterygii:

This remaining actinopterygians belong to Neopterygii and comprise roughly half of vertebrate diversity. Living neopterygians include:

- Lepisosteiformes: (Jurassic - Quaternary) Gar fish and their immediate fossil relatives (Seven extant species).

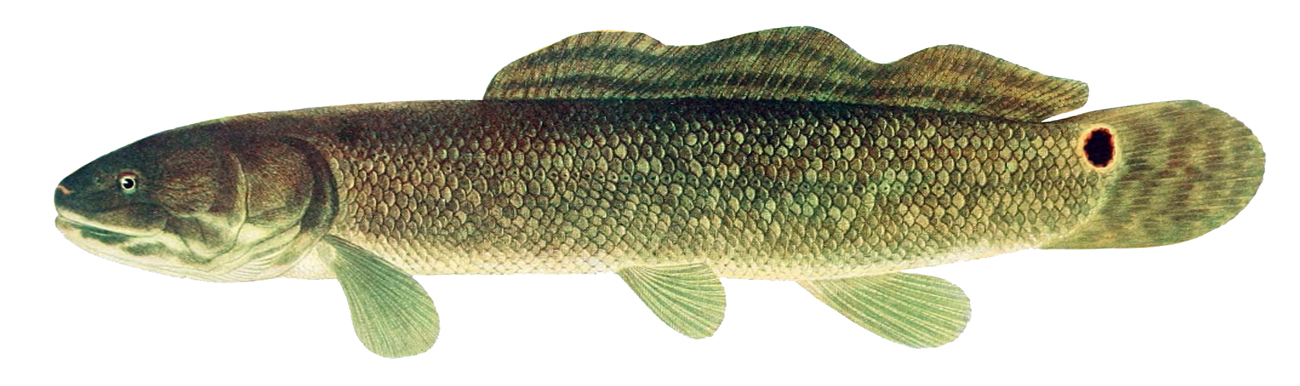

- Amiidae: (Jurassic - Quaternary) Bowfins and their fossil relatives (One extant species).

- Teleostei: (Triassic - Quaternary) The vast diversity of derived actiniopterygians (~28,000 extant species).

This huge radiation seems to have resulted from signifcant morphological adaptations beginning with:

- Modification of the cranial skeleton to facilitate suction-feeding.

- Coordinated reduction of body scales and elaboration of the vertebral column

- A full-genome gene duplication event at the base of crown-group Teleostei that greatly increased the amount of genetic variation for natural selection to work with.

Dipteronotus gibbous

- The maxilla is long, expands onto the cheek behind the orbit, and is firmly attached to adjacent bones.

- Heavy ganoid scales

- Heterocercal tail

Schematic of Cheirolepis, a non-neopterygian and Amia, a neopterygian

- opens dorsally, allowing these muscles to originate from the side of the braincase as well

- expands laterally increasing the number of muscle fibers.

- The muscle mass came to insert on a coronoid process extending dorsally from the jaw.

- The jaw articulation shifted below the line of the tooth row.

- The hyomandibula and preopercular became roughly vertical, with the hyomandibula hinged to the neurocranium in such a way as to rotate laterally.

Parasemionotus

- The maxilla shortened and became detached from other bones of the skull roof, acquiring a new anterior peg-and-socket articulation with the palatoquadrate. As a result, it became able to rotate downward when the mouth opens. (It's structural role in the side of the face was taken over by an expanded series of infraorbital bones.)

- A new element, the supramaxilla (sm) was attached to it dorsally.

- A new opercular element, the interopercular (iop) served to close the gap between the opercular series and jaw.

Parasemionotidae indet.

- the tail remains heterocercal, but in most forms is superficially symmetrical

- Although the tail remains heterocercal, the caudal fin is supported above the notochord by epurals (ep. right) - specialized supraneurals of the tail.

- we begin to see a tendency toward the ossification of the notochord in the form of spool-shaped centra in some members. (Note: We have already seen the independent acquisition of centra in Polypteriformes.)

Lepisosteus sp.

Ginglymodi:

(Triassic - Quaternary) Living Lepisosteidae, gars (Cretaceous - Quaternary) and their fossil relatives. Gars are specialized ambush predators. Their skulls are highly derived in having long, drawn-out jaws. Posteriorly, they are more primitive, with heavy ganoid scales and heterocercal tails (albeit outwardly almost symmetrical.)

Lepisosteus

- There is no interopercular

- The tiny reduced maxilla has no supramaxilla

- The dermohyal is present

- The snout is elongate

- The jaw articulation is below the tooth row and well in front of the orbit

- The preopercular (?) is positioned at the ventral margin of the cheek and rotated 90 degrees.

- The cheek region is made up of a mosaic of small elements.

- The maxilla is greatly reduced.

- Notochord ossifies as a series of opistocoelous centra: I.e. centra that are convex anteriorly and concave posteriorly. This is a very unusual condition for fish vertebrae and makes even fragmentary fossil gars readily identifiable.

Fossil Ginglymodi:

Obaichthys decoratus

Semionotiformes (Middle Triassic - Middle Cretaceous) A very speciose Mesozoic radiation whose members share with lepistosteids:

- a jaw articulation even with or anterior to the orbit

- a proliferation of infraorbital elements forming a mosaic in the cheek region.

- mobile maxilla

- supramaxilla

- interopercular

Semionotiformes are interesting in their own right, as one of the best documented fossil examples of species flocks - radiations of closely related species occupying adjacent ecological niches in the same general environment, and distinguishable by body shape, color, and scale pattern. A modern example is that of African rift valley lake cichlids. During the Late Triassic, similar flocks of semionotiformes occupied similar environments - the rift valley lakes of the Newark Supergroup.

Halecomorphi:

(Triassic - Quaternary) Living Amia calva and fossil Amiiformes, (Jurassic - Quaternary) and their other fossil relatives. Freshwater ambush predators. In them, the rest of the body begins to catch up, evolutionarily, with the head:

- The notochord ossifies as spool-shaped amphicoelous (concave on both ends) centra. In the caudal region, two centra ossify for each myomere.

- Body scales are reduced in thickness, with the vascular layer and ganoine reduced.

But the mouth is not static. As emphasis increases on suction-feeding, the role of the hyomandibula in the lateral expansion of the palatoquadrate increases. In halecomorphs and Teleosts, we see the symplectic, a new ossification directly linking the hyomandibula to the quadrate, the ossification of the palatoquadrate forming the jaw joint. Together, the hyomandibula, symplectic, and quadrate form the suspensorium - the primary load-bearing attachment of the jaws to the neurocranium.

Fossil halecomorphs:

Amiiformes (Jurassic - Quaternary) Members of Amiiformes extend back to the Jurassic and include both fresh water ambush predators similar to the living Amia calva, marine pursuit predators such as Ionoscopus (Late Jurassic - right). Note that Amia's long dorsal fin is derived within the group.

Parasemionotidae: (Early Triassic) Basal, small relatively unspecialized halecomorphs.

Synapomorphy of Halecomorphi:

- The jaw articulates both with the quadrate (ossification of the palatoquadrate) and the symplectic.

Neopterygian phylogeny headache:

Alas, there is no consensus on the phylogenetic pattern formed by Ginglymodi, Halecomorphi, and Teleostei (the derived actinopterygians). Two hypotheses compete:

- The Holostei hypothesis: Prior to the rise of phylogenetic systematics, non-teleosts with the derived neopterygian condition were lumped into this group of unknown monophyly. The first phylogenetic analyses found it to be paraphyletic, however during the last decade, this "ancient fish clade" has experienced a resurgence in phylogenetic analyses and represents the current consensus (Argyriou et al. 2022). Potential synapomorphies concern details of the articulation of the premaxilla, and enervation of the snout.

- The Halecostomi hypothesis: would group Halecomorphi and Teleostei, based on characters such as the presence of the symplectic. Analyses of the 1980s and 90s that recovered this clade often lacked complete information on stem halecomorphs, ginglymodans, and teleosts, causing features like the presence of the interopercular or supramaxilla to look like a halecostome synapomophy when, in fact, they diagnosed neopterygii.

A victim of the headache: Pycnodontiformes (Triassic - Paleogene) Distinguished by:

- Deep bodies

- Longish snouts full of teeth specialized for crushing, and front incisors for nipping

- Body scales reduced to long bars on the front half of the body.

- There is no interopercular or supramaxilla

- Notochord is unossified

- The maxilla is loosely attached and assumed to be mobile

- The caudal fin is outwardly symmetrical, as in halecomorphs and teleosts.

- A symplectic is present

- Poyato-Ariza, 2015 place Pycnodontiformes, instead, as a basal branch of Neopterygii.

- Argyriou et al. 2022, the latest word, show them as sister taxon to Holostei.

But wait! What is Teleostei?: Wait for it.

Teleost Phylogeny

Teleostei: (Triassic - Quaternary) The vast majority of living actinopterygians belong to this highly derived clade, with significant apomorphies of:

- Skull morphology

- Caudal skeleton morphology

- Genomics and development

- Modification of the mouth for suction-feeding

- Evolution of an outwardly symmetrical homocercal tail

- Ossification of the vertebral column

We follow the taxonomic nomenclature of Arratia 2013 where:

- Teleosteomorpha: (Triassic - Quaternary) The Teleost total-group - everything closer to living teleosts than to Amiiformes or Lepisosteidae.

- Teleostei: (Triassic - Quaternary) An apomorphy-based group - The first creature to possess the characteristic apomorphies traditionally associated with teleosts, and all of its descendants.

- Elopocephala: (Jurassic - Quaternary) The Teleost crown-group - the last common ancestor of living teleosts and all of its descendants.

Parasemionotidae indet.

Teleost Tails

Because teleost evolutionary change is focused in the caudal region, let's establish a basic vocabulary.

Ancestral neopterygian: A review. The caudal skeleton contains:

- Typical neural arches (npu - right)

- Typical haemal arches (hpu - right)

- Epurals, specialized supraneurals of the tail dorsal to the norochord. (ep - right)

- Hypurals, specialized haemal arches of the tail. (h - right) Whereas typical haemal arches protect major blood vessels by arching over them, in hypurals the relationship is reversed and the vessels flow laterally to the arches. Major concept: The presence of hypurals distinguishes the ural region.

- Caudal fin rays (not shown). Ancestrally these all arise from the hypochordal lobe of the tail.

Pholidophorus bechei

- Neural arches and intercalaries are associated with calcifications of the notochord.

- Hypurals have become significant support of caudal fin rays, with a clear division of labor:

- Hypurals 1 and 2 support fin rays of the lower lobe

- Hypurals 3 - 8 support fin rays of the upper lobe

- (The big thing) Uroneurals (una - right) The neural arches of the ural region are radically transformed, being:

- Paired rather than fused on mid-line.

- Elongate and overlapping.

- Epurals are de-emphasized.

The net effect is:

- The specialization of arches associated with the caudal fin

- Their physical consolidation at the end of the tail

- A distinction between elements associated with the tail's upper and lower lobes.

Stem Teleosteomorph Superlatives

Aspidorhynchus acutirostris

Aspidorhynchiformes: (Cretaceous - Paleogene) Long - bodied, medium-sized predatory fish with heavy ganoid scales, long pointed snouts, and a unique pattern of ossification of the skull. United with Teleosteomorpha by the possession of distinct uroneurals.

Pachycormiformes: (Jurassic - Cretaceous) Large to gigantic fish with pointed snouts, long blade-shaped pectoral fins, and reduced pelvic fins. These invaded marine niches including:

- "billfish-mimic" pursuit predators, including Protosphyraena

- Giant suspension feeders analogous to modern basking sharks or baleen whales. The "big" example - the 16 m. Leedsichthys.

As with aspidorhynchids, the connection between pachycormids and teleosts is found in the tail, where hypurals are not merely specialized but fused into a hypural fan. And yet, these animals show no tendency to ossify their notochords. In fact, these tend to be poorly ossified in comparison to other neopterygians.

Pholidophorus sp. palatal view of skull. Vomer in blue.

- Vomers are fused into a single mid-line palatal element.

Oreochima sp. a Jurassic pholidophorid.

Teleostei trends and synapomorphies:

Pholidophoridae, (Triassic - Cretaceous), the most basal member of apomorphy-based Teleostei is our model of their basal condition. Pholidophorids were small predatory fish.

The neurocranium: Compare the braincases of Mimipiscis, a basal "paleoniscoid" with Pholidophorus.

Mimipiscis (left) and Pholidophorus (right). Lateral views of neurocranium.

Evolutionary Trends:

- The neurocrania of basal actinopterygians tend to ossify into a single unit. Among teleosts, ossification does not progress so far that individual centers of ossification - endochondral bones of the braincase - can't be distinguished. Alas, these are mostly conventionally named after their sarcopterygian analogs. Thus, as with the skull roof, you may never assume that the "exoccipital" of a teleost is truly homologous with that of a sarcopterygian.

- However the ancestral fissures of the eugnathostome braincase have been closed or overgrown by other bones:

- The lateral cranial fissure is largely closed. Its remnants are the otico-occipital fissure and the vestibular fontanelle.

- The ventral cranial fissure has been overgrown by the parasphenoid and is only visible in cross-section.

- Ancestrally, the four posterior extrinsic muscles of the eye originated in a small myodome an excavation in the posterior wall of the orbit. In teleosts, the myodome becomes quite large, but is only readily visible in cross-section.

- Across Neopterygii, we saw a trend toward the reduction of the spiracle. This continues in Teleostei, and is reflected in the obliteration of the spiracular groove.

- Ancestrally, the axial muscles of the trunk insert on the occipital (posterior) surface of the skull. In Teleostei, these insertions are developed as pits called posttemporal fossae.

The skull roof: Compare the braincases of Watsonulus, a halecomorph with Pholidophorus.

Watsonulus, a halecomorph (left) and Pholidophorus, a teleost (right). Lateral views of dermal skull roof.

- Teleosts have at least two supramaxillae.

- The premaxilla ossifies as two elements, a mobile tooth-bearing premaxilla and a median dermethmoid.

- The (dermal) "quadratojugal" is fused to the (endochondral) quadrate. (Link to image of tarpon (Megalops cyprinoides.))

Synapomorphies of Teleostei - The List:

- At least two supramaxillae.

- Premaxilla ossifies as mobile tooth-bearing premaxilla and a median dermethmoid.

- Quadratojugal and quadrate fused.

- Posterior myodome extends into posterior braincase.

- Caudal neural arches become paired overlapping uroneurals

Teleost Diversity

Gillicus arcuatus inside Xiphactinus audax from Wikipedia.

Link to D. Bogdanov reconstruction of Xiphactinus

- Protruding jaw yielding a bulldog-faced appearance. (In some cases very pronounced E.G. Saurodon.)

- Enlarged premaxillary fangs

Potential synapomorphies of Ichthyodectiformes and Elopocephala:

- Notochord ossifies as vertebral centra.

- Uroneurals that extend forward to reinforce the sides of the pre-ural centra (Link to Xiphactinus specimen). As teleost evolution unfolds, we see their gradual reduction as other methods for stabilizing the tail evolve.

- Elopomorpha: (Jurassic - Quaternary) Tarpons, bonefish, eels, etc.

- Osteoglossomorpha: (Cretaceous - Quaternary) Arapaimas, arrowanas, mooneyes.

- Clupeomorpha: (Cretaceous - Quaternary) Herring, anchovies, etc.

- Ostariophysi: (Cretaceous - Quaternary) Carp, minnows, characins, catfish etc.

- Salmoniformes: (Cretaceous - Quaternary) Salmon, trout, grayling, etc.

- Esociformes: (Cretaceous - Quaternary) Pikes, pickerels, etc.

- Neoteleostei: (Cretaceous - Quaternary) Everything else.

Synapomorphies of Elopocephala: Exist but are highly technical and depend largely on reversals. E.G.:

Pholidophorus, a basal teleost (left) and Leptolepides, an elopocephalan (right). Lateral views of dermal skull roof.

- Loss of extensive sensory canals radiating from the preopercular canal.

Elopocephalan diversity

Anaethalion sp. (Jurassic elopomorph)

Osteoglossomorpha: (Cretaceous - Quaternary). Living forms occupy the fresh waters of former Gondwana, although earlier distribution included North America and Asia. Synapomorphy:

- Toothed "tongue". Teeth on the midline basihyal oppose teeth on the palate, forming what amounts to a second set of "jaws" inside the mouth.

Lycoptera (Cretaceous)

The osteoglossomorph caudal skeleton is plesiomorphic. Note that:

- Four uroneurals still extend along the preural centra.

- Hypurals 1 and 2 each are associated with separate centra.

Diplomystus dentatus

- The lung (aka swim-bladder used at least as much for hydrostatic bouyancy regulation as for breathing) is coupled to the occipital surface of the neurocranum and serves to transmit sound to the otic capsule.

Otocephalan diversity: (Jurassic - Quaternary)

- Clupeomorpha: Herring, anchovies, etc. Characterized by:

- Lung/swim-bladder with an anterior diverticulum that invades the exoccipital of the neurocranium. (According to Diogo, 2009, this may be a synapomorphy of Otocephala.)

- Specialized keeled mid-ventral scales

- Ostariophysi: (Jurassic - Quaternary) Carp, characins, catfish, etc. representing ~8000 living species. Characterized by:

- Lung/swim-bladder that is coupled with the perilymphatic ducts of the otic capsule by means of weberian ossicles - specially modified vertebral elements.

Diplomystus dentatus caudal skeleton

- Adipose fin present between dorsal and caudal fin.

- Hypurals 1 and 2 associated with a single centrum (h1 + h2 - right).

- Neural spine of the posteriormost preural neural arch reduced (npu 1 - right).

Gaudryella sp.

Esox lucius

- Scales cover operculum and cheek. (Ancestral, derived state.)

- Teeth are lost from the maxilla. (Link to ancestral and derived states)

- Adipose fin lost.

Neoteleostei: (Cretaceous - Quaternary) Potential synapomorphies of occur at both ends of the animal:

- Vertebral column stabilized by zygapophyses, enabling flexion to be concentrated at base of tail. As a consequence, neoteleosts tend to have shorter vertebral columns.

- The enlargement of the retractor dorsalis muscle (derived from muscles lining the esophagus) enables the tooth-plates supported by the pharyngeobranchials to be moved purposefully. Pharyngeal teeth gain importance relative to those of the palate.

- In teleosts, the lung is used both for supplementary breathing and for hydrostatic equilibrium, so it is often called the swim-bladder.

- Physostomous swim bladders retain their ancestral connection to the esophagus.

- Physoclistous swim bladders lose their connection to the esophagus and are used only for hydrostasis. This condition evolves in Neoteleostei.

- The first ural and first preural centra are fused. Link to Gaudryella (Cretaceous).

Acanthomorpha: (Cretaceous - Quaternary) Here the evolutionary trajectory of Teleostei reaches its full flower. Synapomorphies:

- The tooth-bearing margin of the premaxilla is elongate and approaches the jaw angle. (The maxilla, recall, is toothless.)

- Anterior fin rays of dorsal and anal fins form solid, unsegmented spines.

- Pelvis is translated forward, causing pelvic fins to move beneath or even in front of the pectoral fins. In some, the pelvis articulates to the pectoral girdle.

Spines are an obvious defensive adaptation, that is developed in various ways. In many familiar acanthomorphs, the anterior spiny portion of the dorsal fin is distinct from the remainder, resulting in an anterior spiny dorsal fin and a posterior soft dorsal fin

- Basal groups include forms specialized for deep or cold water, including:

- Gadiformes (cod - Late Cretaceous - Quaternary)

- Zeiformes (dories - Late Cretaceous - Quaternary)

- Lampridiformes (oar-fish and opah - Late Cretaceous - Quaternary)

- Acanthopterygii: (Cretaceous - Recent)

- Synapomorphy: Pelvic fin spine present (Johnson and Patterson, 1993)

This breaks down into two major groups:

- Beryciformes: (flashlightfish, pineconefish, alfonsinos, and other small favorites - Late Cretaceous - Quaternary)

- Holocentriiformes: (squirrelfish - Late Cretaceous - Quaternary) Small fish adapted to dark environments in the photic zone. Often nocturnal.

- Percomorphaceae: (Everything else, - Late Cretaceous - Quaternary)

- Percomorphaceae: (Phylogenetically defined taxon from Betancur et al., 2013 - roughly corresponds to traditional "Percomorpha" - Late Cretaceous - Quaternary) Yet again, the vast majority of actinopterygian diversity. Synapomorphies (from Johnson and Patterson, 1993 concentrated in the tail:

- Second ural centrum absent

- Five or fewer hypurals

- the distal parts of all epineurals displaced ventrally into the horizontal septum.

Percomorphacean diversity: Where to start? Beyond this point, we enter the realm of dragons and unicorns. Morphological systematics has failed to converge on a clear picture of Percomorph phylogeny, however molecular systematists are beginning to. Currently the last word belongs to Betancur et al., 2013 who have provided both a phylogeny and revised taxonomic nomenclature which we follow here. the major pattern:

- The basal branches are deep water or bottom dwelling specialists

- Ophidiiformes: Cusk eels and kin

- Batrachoideformes: toadfish

- Gobiomorpharia: gobies

- Scombriomorpharia: the close relationship between Syngnathiformes (cryptic lurkers in reefs and vegetation - trumpetfish, seahorses, sea dragons) and Scombriformes (apex predators like tuna, mackerel, and more.)

- Percomorpharia: Yet another vast group of disparate fish, containing roughly one third of actinopterygian diversity.

- Carangiamorpharia: The sister taxon of Percomorpharia, contains:

- Ovalentaria: Containing small - medium fish including cichlids, mollies and guppies, mullets, damselfish, silversides, needlefish, half-beaks, and more.

Potential synapomorphy:

- Sticky adhesive eggs.

- Carangiamorphariae: The close relationship between fast swimming predators with laterally compressed bodies like jacks, apex predators like billfish, and at least two radiations of flatfish.

Potential synapomorphies:

- Loss of supraneurals.

- Reduced vertebral count

- Anabantomorphariae: Anabantids (gouramis, Siamese fighting-fish) and kin. Unusual for being an actual fresh-water radiation with a distribution in Africa and Southeast Asia.

Potential synapomorphy:

- Suprabranchial organ or pouch for air-breathing.

- Ovalentaria: Containing small - medium fish including cichlids, mollies and guppies, mullets, damselfish, silversides, needlefish, half-beaks, and more.

Percomorpharia: Peeling away another layer of the endless actinopterygian onion, we reach Percomorpharia. Well known groups and interesting patterns contained within it include:

- Labriiformes: (wrasses and parrotfish)

- The close relationship of Spariformes: (porgies and sea bream) and Tetraodontiformes: (triggerfish, puffers, and boxfish)

- The close relationship of Centrarchiformes (sunfish and kin) and Perciformes: (including among groupers, perch, rockfish, sticklebacks, and much more.)

That a lot of fish.

Emerging Patterns

For all that this is lots of data to process, major patterns in teleost evolution do emerge readily from the background:

The principal radiation of acanthomorphs occurred during the Late Cretaceous.

- At first, they had lots of company from non-teleost neopterygians and basal teleosteomorphs.

- After the K-Pg extinction event, they became dominant. Non-percomorphacean acanthomorphs that are uncommon today, such as Holocentriformes, were very common in Paleogene Lagerstätten such as Monte Bolca.

- Percomorphaceans appear in the Paleogene and become common by the Neogene. Indeed, some major groups don't appear until the Neogene.

2. Percomorphaceae is a Cenozoic radiation:

As such it parallels other vertebrate radiations that followed the K-Pg extinction, including

- Placental mammals

- Neognath birds

3. Major radiations start in the oceans:

With few exceptions (Anabantomorphariae) major actinopterygian radiations occur in the oceans and invade fresh water subsequently. As a consequence, fresh waters serve as a refuge for groups that have been replaced in the oceans. Examples include:

- Xenacanths: Paleozoic elasmobranchs surviving into the Mesozoic

- Hybodontiformes: Late Paleozoic elasmobranchs surviving into the Cretaceous

- Cladistians: Basal actinopterygians surviving in the streams of Africa.

- Chondrosteans: Early Mesozoic actinopterygians surviving to the present in the rivers of Eurasia and North America.

- Catadromous fish, who live in fresh water but return to salt water to reproduce (E.G. anguillid eels.)

- Anadromous fish who live in salt water but spawn in fresh water (salmon)

Introducing "Burden"

Burden 1: Convergent approaches to flatfish

Teleost evolution shows the iterative invasion of the same ecological niches by diverse lineages. Example: Carangimorphariae - transforming something like the green jack(above), a fast predator with a strongly laterally compressed body, into a flattened bottom dweller like a flounder. One option is simply to flop onto one side, but that places one eye is in the mud.

Apparently it is easier for evolution to move one eye to the opposite side of the head than to radically change the shape of the body. This transition is documented by the Paleogene fossils Amphistium and Heteronectes (Friedman, 2008), in which the orbits have become asymmetric but orbital migration is incomplete.

A survey of groups within Carangiomorphariae reveals at least one independent derivations of left-eyed flounders (Paralichthyidae and Bothidae), one of right-eyed flounders (Pleuronectidae) and one group whose members go both ways (Psettodidae).

Burden 2: Air breathing for creatures who gave up lungs

The evolution of the physoclistous swim-bladder allowed the osteichthyan conquest of the deep oceans, but at a cost:

The "lung" could no longer be used for breathing.

Fish that find themselves in need of accessory breathing apparatuses have to improvise evolutionarily. Some strategies:

- Cutaneous breathing: Provided there is a high surface/volume ratio and scales are reduced, oxygen can be absorbed directly through the skin. E.G.: Periophthalmus, the mudskippers, small gobies that inhabit tropical beaches and mudflats; and anguillid eels. (We will see this strategy used by sarcopterygians, also.)

- Labyrinth organ: Anabantids such as gouramis (right) and Siamese fighting-fish employ an organ that is supported by an expanded epibranchial of the first branchial arch. This supports a highly vascularized, pleated chamber into which air can be channeled, effectively "reinventing" the lung. Note: this facilitates both breathing and the construction of bubble-nests in which eggs are brooded.

Additional reading:- Thodoris Argyriou, Sam Giles, Matt Friedman. 2022. A Permian fish reveals widespread distribution of neopterygian-like jaw suspension. Elife. 2022 May 17.

- Gloria Arratia. 2013. Morphology, taxonomy, and phylogeny of Triassic pholidophorid fishes (Actinopterygii, Teleostei).Society of Vertebrate Paleontology Memoir 13. Supplement to Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 33(6): 1 - 138.

- Michael Benton. 2014. Vertebrate Palaeontology. Wiley-Blackwell; 4 edition. 480 pp.

- Ricardo Betancur, Richard E. Broughton, Edward O. Wiley, Kent Carpenter, J. Andres Lopez, Chenhong Li, Nancy I. Holcroft, Dahiana Arcila, Millicent Sanciangco, James C Cureton II, Feifei Zhang, Thaddaeus Buser, Matthew A. Campbell, Jesus A Ballesteros, Adela Roa-Varon, Stuart Willis, W. Calvin Borden, Thaine Rowley, Paulette C. Reneau, Daniel J. Hough, Guoqing Lu, Terry Grande, Gloria Arratia, Guillermo Orti. 2013. The Tree of Life and a New Classification of Bony Fishes. Plos|One. April 18, 2013.

- Robert Carroll. 1990. Vertebrate Paleontology and Evolution. W. H. Freeman and Company. 698 pp.

- Lionel Cavin and Varavudh Suteethorn (2005) A new semionotiform (Actinopterygii, Neopterygii) from Upper Jurassic - Lower Cretaceous deposits of north-east Thailand, with comments on the relationships of Semionotiforms. Paleontology, 49 (2), pp. 339-353.

- John J. Cawley, Giuseppe Marramà, Giorgio Carnevale, Jaime A. Villafaña1, Faviel A. López-Romero, Jürgen Kriwet. 2020. Rise and fall of Pycnodontiformes: Diversity, competition and extinction of a successful fish clade. Ecology and Evolution, 2021;11:1769–1796..

- Rui Diogo. 2009. Origin, Evolution and Homologies of the Weberian Apparatus: A New Insight. International Journal of Morphology, 27(2):333-354.

- Matt Friedman. 2008. The evolutionary origin of flatfish asymmetry. Nature, 454: 209-212.

- Lance Grande and W. E. Bemis (1998). A Comprehensive Phylogenetic Study of Amiid Fishes (Amiidae) Based on Comparative Skeletal Anatomy. An Empirical Search for Interconnected Patterns of Natural History. Memoir (Society of Vertebrate Paleontology) 4: 1–679.

- G. D. Johnson and C. Patterson. 1993. Percomorph phylogeny: A survey of acanthomorph characters and a new proposal. Bulletin of Marine Science. 52, 554-626.

- James Moy-Thomas. 1971. Palaeozoic Fishes. Saunders. 259 pp.

- Thomas J. Near, Ron I. Eytan, Alex Dornburg, Kristen L. Kuhn, Jon A. Moore, Matthew P. Davis, Peter C. Wainwright, Matt Friedman, and W. Leo Smith. 2012. Resolution of ray-finned fish phylogeny and timing of diversification. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 109 (34) 13698-13703.

- Francisco Poyato-Ariza (2015) Studies on pycnodont fishes (I): Evaluation of their phylogenetic position among actinopterygians. Rivista Italiana di Paleontologia e Stratigrafia 121(3) 329-343.

- Guang-Hui Xu, Li-Jun Zhao, Ke-Qin Gao, and Fei-Xiang Wu. 2012. A new stem-neopterygian fish from the Middle Triassic of China shows the earliest over-water gliding strategy of the vertebrates. Proceedings of the Royal Society B, 20122261. http://dx.doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2012.2261.

- Gloria Arratia. 2013. Morphology, taxonomy, and phylogeny of Triassic pholidophorid fishes (Actinopterygii, Teleostei).Society of Vertebrate Paleontology Memoir 13. Supplement to Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 33(6): 1 - 138.

- Thodoris Argyriou, Sam Giles, Matt Friedman. 2022. A Permian fish reveals widespread distribution of neopterygian-like jaw suspension. Elife. 2022 May 17.