Osteichthyes and Actinopterygii

Osteichthyes Introduced:

Definition: The last common ancestor of Actinopterygii (ray-finned fish) and Sarcopterygii (lobe-finned fish).

Osteichthyes weren't the first vertebrates with bone, but they developed and used it in novel ways that cause their skeletons to preserve much more evolutionary information: Major trends:

- Widespread endochondral bone in the braincase and postcranial skeleton.

- Emergence of recognizable dermal elements of the head and pectoral girdle.

- Emergence of a tendency for superficial dermal elements to interact with deeper endochondral ones.

Synapomorphies of Osteichthyes:

A thorough survey goes beyond the technical limitations of this course. If you really want to know, consult the technical literature. For us, a general review must do:

- Bone ossifies endochondrally: Many fossil vertebrates have extensive dermal bone. Osteostraci, Galeaspida, and placoderm-grade gnathostomes have in addition perichondrally ossified three-dimensional bone preformed in cartilage, however in Osteichthyes, there is extensive endochondral ossification as well, in the braincase, girdles, and vertebral elements.

Sensory canals in an Arthrodira and Osteichthyes - Sensory canals: Present in vertebrates ancestrally, but only identifiable in vertebrates with large dermal plates. In Arthrodira we see

- The extension of the main lateral line onto the skull roof.

- Supraorbital canal

- Infraorbital canal

- Preopercular canal

- Mandibular canal

- Occipital commissure

- Jugal canal (in Sarcopterygii)

Other neurocranial synapomorphies:

Neurocranium of Mimipiscis toombsi- Neurocranium articulates with palatoquadrate via basipterygoid process (Although the stem chondrichthyan Pucapampella seems also to have had this (Maisey and Anderson 2001).)

- Postorbital process forms the dorsal surface of a partition called the lateral commissure. the hyomandibula articulates with its posterior surface rather than with the otic process, as in Chondrichthyes.

- Spiracular groove passes between lateral commissure, basipterygoid process and opening of spiracle.

- Endolymphatic duct does not communicate with the external environment.

- The anteroventral extremity of the lateral occipital fissure widens into an unossified vestibular fontanelle adjacent to the sacculus of the inner ear.

Cheirolepis canadensis - Dermal bony plates form dermal skull roof (right), including:

- Paired elements:

- Parietals (p)

- Postparietals (pp)

- Supratemporals (st)

- Intertemporals (it)

- Large cheek plate that houses the preopercular canal. (Named the preopercular (pop) in actinopterygians, and arguably homologous to the preopercular and squamosal in sarcopterygians)

- Median elements:

- Rostral (r)

- Postrostral (por)

- Paired elements:

- Teeth are developed in the dermal bones forming the margin of the mouth (premaxilla, maxilla, dentary) as well as from bones covering the palatoquadrate and Meckel's cartilage.

- Dermal bones enclose Meckel's cartilage. Adductor muscles insert on Meckel's cartilage through an adductor fossa.

Synapomorphies of Mandibular arch:

- Dermal bones of the jaw:

- At least one infradentary beneath dentary on medial surface

- Prearticular medial to adductor fossa

- Coronoid series anterior to adductor fossa.

Palate of Mimipiscis showing dermal elements. - Dermal bone lines the palate:

- Vomers (v)

- Pterygoids (pt)

- A lateral arcade of palatal elements

Hyoid and branchial arches of Mimipiscis.

- Dermohyal - Dermal ossification of the hyomandibula:

- Branchiostegal rays with at least two elements modified as operculars and suboperculars (in contrast to their status in acanthodians).

- Hyoid arch cartilages ossify as:

- Hyomandibula (eh) ("epihyal" of some authors) and interhyal (ih) dorsally

- Ceratohyal (ch) and hypohyal ventrally.

Synapomorphies of branchial arch:

- First two branchial arches articulate to a single basibranchial

- Cleithrum (ct) (which adheres to the lateral aspect of the endochondral scapulocoracoid.)

- Dorsal to the cleithra (in order).

- Anocleithra (aka postcleithra)

- Supracleithra

- Posttemporals

- Ventral to the cleithra

- Clavicles

- Interclavicle (single midline element)

Lepidotrichia from dkimages.com

- Fins supported by lepidotrichia - dermal fin rays developed from modified rows of scales.

- Lungs - outpouchings of the esophagus serving as an accessory breathing mechanism. (Modified in some as a "swim-bladder" for hydrostatic control.) Byrne et al., 2020 consider this a potential evolutionary response to high tide ranges, causing fish who become trapped in tide pools to experience selective pressure for means of coping with hypoxia because:

- Air typically has 20 to 30 times the oxygen concentration of water.

- In hypoxic environments, oxygen can actually diffuse out of the fish and into the water through gills. (Pelster, 2021.)

What the first lung looked like is debated. The traditional view is that they originated as paired out pouchings of the pharynx, however Cupello et al., 2022 suggest that the original lung was unpaired, with pairing arising secondarily within Sarcopterygii.

- Primary fin supports make minor contribution to median fins outside body wall.

- Rhombic body scales with peg and socket articulation.

- Fulcral scales support leading edges of fins.

Mimipiscis neurocranium

- Persistent lateral occipital fissure (lateral cranial fissure of some authors)between otic and occipital regions.

- Persistent Ventral cranial fissure in floor of braincase between otic (parachordal) and sphenoid (trabecular) regions.

- The post-cranial axial skeleton is simple:

- The notochord is not ossified

- Neural arches protect the nerve cord dorsal to the notochord

- Ribs may project from the notochord in the trunk region

- Haemal arches protect blood vessels ventral to the notochord

- Supraneurals may extend from the neural arches

- Occasionally, intercalary ossifications (aka "intercalaries" - not shown) form between neural or haemal arches.

- Fin ray radials support the median fins.

In most Paleozoic osteichthyes, heavy body scales take up much of the mechanical load that is born by the axial skeleton in later fish.

Latimeria menadoensis (Sarcopterygii) and Xyrauchen texanus (Actinopterygii)

Osteichthyan Diversity

Two major living groups:

- Actinopterygii (Devonian - Quaternary) - Living ray-finned fish and their fossil relatives.

- Sarcopterygii (Silurian - Quaternary) - living lobe-finned fish (including tetrapods) and their fossil relatives.

Moythomasia nitida (Actinpoterygii) and Strunius sp. (Sarcopterygii)

Body profile:

-

Actinopterygii:

- Single dorsal fin

- Tail is heterocercal. Epichordal lobe lacks fin rays. Instead, it is lined by robust fulcral scales

- Two dorsal fins

- Tail is diphycercal in the most basal forms. Even those that evolve heterocercal tails retain epichordal fin rays.

Sarcopterygii:

Xiphias gladius (Actinpoterygii) and Sauripteris taylori (Sarcopterygii)

Paired limb skeleton:

-

Actinopterygii:

- Parallel endochondral distal radials articulate with proximal radials which articulate with the endochondral scapulocoracoid

- Pre- and postaxial elements branch from a metapterygial axis.

- Thus, a single humerus articulates with the endochondral scapulocoracoid, followed by radius and ulna, etc.

Sarcopterygii:

Mimipiscis toombsi (Actinpoterygii) and Eusthenopteron foordi (Sarcopterygii)

Braincase:

-

Actinopterygii:

- Strongly integrated or coossified endochondral braincase.

- Hyomandibula articulates through a single articular surface dorsal to the jugular vein.

- Ethmosphenoid region and otico-occipital regions completely separated by ventral cranial fissure and meet at a mobile joint.

- Hyomandibula articulates through two articular surfaces between which the jugular vein passes.

Sarcopterygii:

Ganoid scale (Actinpoterygii) and cosmoid scale (Sarcopterygii)

Scales:

-

Actinopterygii: Ganoid scales

- Scales form as concentric bony layers around a primordium, as in Acanthodii.

- However superficial layers are of dentine and deep layers of acellular bone, separated by by a vascularized layer.

- Superficial surfaces of upper layers are made of thick layers of ganoine - an enamel-like substance.

- Typically lack ganoine (although the most basal members have it.)

- The cosmine layer is, instead, covered by a thin lamina of enamel, forming the scale surface.

Sarcopterygii: Cosmoid scales

Osteichthyan Origins

Actinopterygii and Sarcopterygii are total groups that include all members on their stems. Thus, every member of Osteichthyes is, by definition, a member of Actinopterygii or Sarcopterygii. Nevertheless, we should expect to find "stem osteichthyans" displaying some of the osteichthyan synapomorphies. Alas, only a handful of candidates are known:

- Dialipina: (Early Devonian - right) Described as a basal actinopterygian based on its possession of ganoid scales. Clement et al., 2018, however, recover it as a stem osteichthyan.

- Two Late Silurian taxa known from isolated bones and scales including jaw fragments (Botella et al., 2007). In these, fragments of the maxilla and dentary display teeth that grade into families of dermal denticles similar to the tooth families of chondrichthyans.

- Ligulalepis: (Clement et al., 2018) Well known from skull roof and braincase remains displaying placoderm, chondrichthyan, and osteichthyan characters; and pectoral girdle elements reminiscent of Actinopterygians. (Burrow et al., 2023)

Dialipina markae

- Scale histology is not so straightforward:

- It was only recently found that ganoine occurs in both actinopterygians and stem osteichthyans. Until the last decade, a fish with ganoid scales would have been assumed to be an actinopterygian.

- Conversely, Meemania, a basal actinopterygian, has cosmic scales (Lu et al., 2016)

- Prior to the era of cladistics, "stem-Osteichthyes" was not part of our search-image.

But the most significant landmarks are closer to the osteichthyan node. Our most informative example:

- Guiyu (Right. Late Silurian Zhu et al. 2009) is:

- The oldest known osteichthyan.

- Our closest well-known approximation of the last common ancestor of Osteichthyes.

- Stout pectoral and dorsal fin spines

- Ganoine covering surface of dermal bones of skull

- Dermal elements of the pelvic girdle, a feature otherwise only known in the antiarch Parayunanolepis (Zhu et al., 2012).

- A prerostral on the midline of the palate - an element otherwise seen only in placoderm-grade gnathostomes.

Guiyu and its similar close relative Psarolepis are eugnathostomes for sure, but they remember their placoderm-grade origins.

Actinopterygii:

Living actinopterygians are so highly derived that their basic synapomorphies are hard to see. These are visible, however, in fossil taxa like Cheirolepis (right) from the Devonian, the oldest well-known actinopterygian and phylogenetically the most basal. A full exploration of the synapomorphies of Actinopterygii and its constituent clades is beyond the scope of this course. The ones we do track will pertain to four major trends in actinopterygian evolution.

Actinopterygian evolutionary trends:

- From biting to sucking:

The jaws of the ancestral actinopterygians like Moythomasia relied on the scissor-like action of the upper and lower jaws to bite and hold prey. Derived actinopterygians employ a suction feeding mechanism, in which the the mouth extends to form a tube while the pharynx is expanded, sucking prey items in. Once inside, prey is dealt with by any of a variety of jaw, tongue, or pharyngeal teeth. To achieve this, the premaxilla and maxilla have become extremely mobile. (A modest example)

Basal sarcopterygian vertebral column - Ossifying the vertebral column:

- The ancestral osteichthyan had ossified neural and haemal arches, but the notochord remained unossified.

- Among both actinopterygians and sarcopterygians, the vertebral column ossifies as proper bone (in a variety of patterns), yielding vertebrae that represent a close association of:

- Centra

- Neural arches

- Haemal arches

- Making the tail symmetrical: During actinopterygian evolution, caudal vertebrae and their associated hamael arches shorten, curl up sharply, and fuse into a small number of triangular elements that support a superficially symmetrical - looking tail termed homocercal.

Actinopterygian Homology Headache:

Newcomers to actinopterygian paleontology confront a frustrating amount of disagreement about the names of actinopterygian dermal head skeletal elements. This is because in literature published prior to the 1990s, such elements were named based on the similarity of their topographic position on the skull to the cranial elements of sarcopterygians, including tetrapods. Thus, the paired bones between the orbits were called frontals, because they occupied the same general position as the frontals of tetrapods, even though they enclosed the pineal foramen. This results in two problems:

- Many actinopterygian cranial element names suggest homologies for which there is no good evidence. In these notes, I place such names in "quotation marks."

- At least some have sarcopterygian homologs with different names. Since the 1990s, researchers like Hans-Peter Schultze have attempted to verify the homologies of actinopterygian skull bones and adjust their names accordingly (see Schultze, 1993).

Note, also, that in derived actinopterygians, the homologies of the elements shown at right can be obscured when:

- New elements such as suborbitals appear

- Elements of known homologies fuse (E.G. the dermopterotic = supratemporal + Intertemporal) or fragment.

Synapomorphies of Actinopterygii:

- CaCO3 otoliths: CaCO3 structures that fill the sacculus or utricle of the inner ear.

- Mandibular sensory canal enclosed by dentary.

- Single dorsal fin (right).

- Anterior of dorsal and anal fins reinforced by narrow parallel radials (right).

- Caudal radials much shorter than haemal arches.

Actinopterygian Diversity:

Groups with living representatives include:

- Cladistia: Includes living Polypterus and Erpetoichthys, and fossil relatives.

- Acipenseridae: Sturgeons

- Polyodontidae: paddlefish

- Ginglymodi: Gars and fossil relatives.

- Halecomorphi: Bowfins and fossil relatives.

- Teleostei: The majority of living ray-fins, from goldfish to blue marlins.

Basal Actinopterygii:

Although controversial, most phylogenies agree that the Middle - Late Devonian Cheirolepididae (monogeneric for Cheirolepis) is the basal branch. There follows a speciose and morphologically disparate paraphyletic assemblage, traditionally called "paleoniscoids." They represent the major diversification of actinopterygians during the Late Devonian and Carboniferous, with many members surviving well into the Mesozoic. Alas we can only touch on them.

Cheirolepis canadensis

Plesiomorphies:

- Retains a small tuft of epichordal caudal fin rays.

- Pelvic fins still reflect their origin as elongate postbranchial fin folds.

Autapomorphy:

- Extremely small scales.

From this point onward, we follow the result of Giles, et al., 2017, noting its differences with older hypothesis commonly cited in technical literature.

"Paleoniscoids:"

(Devonian - Cretaceous) A host of fossil forms are closer to living "crown Actinopterygii" than to Cheirolepis. Traditionally termed "Paleoniscoids" after Paleoniscum. Their derived features include:

- Palatal toothplates on the vomers.

- branching lepidotrichia

- Heterocercal caudal fin, completely lacking epichordal fin rays.

- Midline canal in posterior ventral braincase for the dorsal aorta. (Link to skull of Mimipiscis in palatal view.)

- teeth capped with acrodin, a unique enameloid tissue.

- Parasphenoid with dorsal processes that interact with neurocranium.

- Propterygial canal: The propterygium - the anterior basal element of the pectoral fin houses a prominent vascular canal.

- Comparatively short ethmoid region

- The maxilla extends far behind the orbit and the preopercular slopes anteriorly.

- A small number of large elements encircle the orbit.

- Heavy ganoid scales.

- Strongly heterocercal tail

Redfieldius gracilis

Note that starting in the Early Carboniferous, "paleoniscoids" also included deep-bodied forms, and forms with special feeding adaptations. Wilson et al., 2021 suggest that the Famenian extinction event freed actinopterygians from ecological constraints enabling them to radiate into new niches, similarly to chondrichthyans at the same time.

Crown Actinopterygii:

Polypterus bichir

- a row of small post-spiracular bones

- a parasphenoid that extends the entire length of the braincase

- a dorsal fin divided into a series of finlets

- a protocercal tail

Ecologically convergent on sarcopterygian lungfish in their ability to tolerate changing conditions in ephemeral pools and streams and their need to supplement gill-derived oxygen with air. Indeed:

- Their lungs show the ancestral condition retained by sarcopterygians - communicating ventrally with the esophagus, begin development as single, but become secondarily paired during development.

- Although they can remain out of water for considerable periods, they will drown if not given access to air.

- They are known to breathe air through their dorsally positioned spiracles. (Could this have been a common practice among other osteichthyans with similar spiracle configurations?)

Fossil cladistians: Recent discoveries pull crown-cladistians into the Cretaceous:

- Serenoichthys kemkemensis: (Late Cretaceous) (Dutheil, 1999) Known from two headless specimens, a small, relatively stout polypteriform.

- Bawitius bartheli: (Late Cretaceous) (Grandstaff et al., 2012) Known from ectopterygoids (palatal bones). Extrapolating based on their size, the entire fish may have approached two meters in length.

The last word for 2025: Previous authors had considered Cladistia basal to all actinopterygians but Cheirolepis, invoking a ghost lineage extending from the Devonian to the Cretaceous! Newer analyses have moved Cladistia much farther up the tree, in the process placing well known fossil taxa onto its stem:

- Giles, et al., 2017 recover the Triassic group Scanilepiformes (like Beishanichthys - right) as stem Cladistians. Argyriou et al. 2022 also recover Brachydegma, Birgeria, and others on the cladistian stem.

/p>

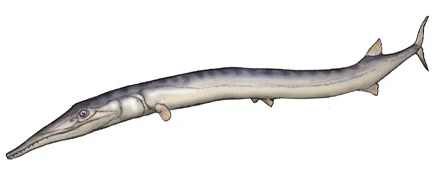

Birgeriidae (Triassic) Large (1.2 m) robust pelagic predators ecologically similar to tuna or mackerels.

Actinopteri:

(Triassic - Quaternary) The last common ancestor of all living actinopterygians excluding Polypteriformes. The crown of Actinopteri includes:

- Chondrostei: Includes living sturgeons and paddlefish, and their fossil relatives.

- Neopterygii: Gars, bowfins, teleosts, and their fossil relatives.

- Supraorbital bones present.

- Intertemporal fused with supratemporal to form dermopterotic

- Parasphenoid extends across ventral cranial fissure. (Independently derived within Cladistia.)

Prominent issues: Although speciose, Paleozoic actinopterygians tended to be small, and a minor component of faunas in which large placoderm-grade fish (prior to Devonian extinctions), chondrichthyans and sarcopterygians figured prominently. The actinopteran radiation, in contrast:

- Was a Mesozoic radiation. That event seems to have released Actinopteri from ecological constraints.

- Included large fish as well as small ones.

Stem Actinopteri:

Of special interest - Saurichthyidae (Late Permian - Middle Jurassic) Long (0.5 - 1.5 m) slender long-jawed predators superficially resembling houndfish or gars. Vaguely like a sturgeon trying to be a barracuda. Generally considered close relatives of sturgeons, but recently placed just outside of crown-group actinopterygii by Giles, et al., 2017.

Body elongation: Within this group, Maxwell, et al., 2013 show a unique mode of elongation of the vertebral column. Whereas other vertebrates either:

- increase the length of vertebrae

- increase the overall number of myomeres

- Chondrostei: Sturgeons, paddlefish, and their fossil relatives

- Neopterygii: Gars, bowfins, and teleosts, and their fossil relatives.

Chondrostei:

Living chondrosteans:

- Acipenseridae (sturgeons - Cretaceous - Quaternary) Large fish of Eurasian and North American rivers and lakes, these notable as the source of caviar. Predators taking prey from the bottom. Interesting morphological features:

- Body scales are lost but for five rows of heavy plates.

- The small jaws are hyostylic.

- Polyodontidae (paddlefish - Cretaceous - Quaternary) Large suspension feeders of China and North American rivers and lakes. Interesting morphological features:

- A long paddle-shaped rostrum can be up to a third of the body length

- Ram suspension feeders, straining food from the water by gill-rakers projecting from the branchial arches.

Among chondrosteans, sturgeons and paddlefish are sister-taxa. Their synapomorphies tend to be associated with extreme reduction of ossification:

- Opercular lost, leaving the subopercular to support the operculum

- Fewer than four branchiostegal rays

- Extensive rostrum supported by dorsal and ventral rostral bones.

- Ventral bones of the rostrum form a distinct keel.

Living chondrosteans significantly reduce their amount of endochondral ossification. Examining fossil chondrosteans, one sees that this is a derived feature. (Also conversantly derived in other large actinopterygian suspension-feeders.)

Fossil Chondrosteans:

- Chondrosteidae (Early Jurassic) Large (0.5 - 1 m) fish broadly similar to sturgeons or paddlefish but lacking specializations such as their long rostra, but showing significant loss of ossification of the skull roof that effectively disconnects the mandibular arch from the skull roof, and modification of the mandibular arch facilitating its protrusion.

Chondrosteus acipenseroidesTogether, sturgeons, paddlefish, and chondrosteids make up Chondrostei. Synapomorphies include:

- Palatoquadrates meet in an anterior symphysis. (taking the place of stabilizing articulations to the neurocranium.)

- "Quadratojugal" connects maxilla to palatoquadrate posteriorly. (Allowing the maxilLa to move with the palatoquadrate.)

- "Preopercular" reduced to a series of ossicles housing the preopercular canal

- A tall triangular suborbital bone makes up the anterior margin of the cheek.

- Mandibular canal is short or absent

- Body scales reduced to tiny elements

Chondrosteus acipenseroides

- Edward Phelps Allis (1922) The cranial anatomy of Polypterus with special reference to Polypterus bichir. Journal of Anatomy. 56(Pt. 3-4): 189 - 294.

- Hector Botella, Henning Blom, Markus Dorka, Per Erik Ahlberg & Philippe Janvier (2007) Jaws and teeth of the earliest bony fishes. Nature 448, 583-586.

- Carole J. Burrow, Gavin C. Young, Jing Lu. 2023. JDermal skeleton of the stem osteichthyan Ligulalepis from the Lower Devonian of New South Wales (Australia). Spanish Journal of Paleontology 38 (1), 23–36.

- H. M. Byre, J. A. M. Green, S A. Balbus, and P. E. Ahlberg. 2020. Tides: A key environmental driver of osteichthyan evolution and the fish-tetrapod transition. proceedings of the Royal Society A, 476:20200355.

- Alice M Clement, Benedict King, Sam Giles, Brian Choo, Per E Ahlberg, Gavin C Young, John A Long. 2018.Neurocranial anatomy of an enigmatic Early Devonian fish sheds light on early osteichthyan evolution. eLife 2018;7:e34349

- Camila Cupello, Tatsuya Hirasawa, Norifumi Tatsumi, Yoshitaka Yabumoto, Pierre Gueriau, Sumio Isogai, Ryoko Matsumoto, Toshiro Saruwatari, Andrew King1, Masato Hoshino, Kentaro Uesugi, Masataka Okabe, Paulo M. Brito, 2022. Lung evolution in vertebrates and the water-to-land transition . eLife 11:e77156.

- Didier Dutheil (1999) The first articulated fossil cladistian: Serenoichthys kemkemensis, gen. et sp. nov., from the Cretaceous of Morocco. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology, 19(2), pp. 243-246.

- Matt Friedman, and Martin Brazeau (2010) A reappraisal of the origin and basal radiation of the Osteichthyes. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology, 30:1, 36-56.

- Sam Giles, Michael I. Coates, Russell J. Garwood, Martin D. Brazeau, Robert Atwood, Zerina Johanson and Matt Friedman (2015) Endoskeletal structure in Cheirolepis (Osteichthyes, Actinopterygii), An early ray-finned fish. Palaeontology. 58:5, 849-870.

- Sam Giles, Guang-Hui Xu, Thomas J. Near and Matt Friedman (2017) Early members of 'living fossil' lineage imply later origin of modern ray-finned fishes. Nature 549, 265–268.

- Barbara Grandstaff, Joshua Smith, Matthew Lamanna, Kenneth Lacovara & Medhat Said Abdel-Ghani, (2012) Bawitius, gen. nov., a giant polypterid (Osteichthyes, Actinopterygii) from the Upper Cretaceous Bahariya Formation of Egypt. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology, 32(1), pp. 17-26.

- Jing Lu, Sam Giles, Matt Friedman, Jan L. den Blaauwen, Min Zhu (2016) The Oldest Actinopterygian Highlights the Cryptic Early History of the Hyperdiverse Ray-Finned Fishes. Current Biology 26(12), 1602 - 1608.

- John Maisey and M. Eric Anderson, (2001) A primitive chondrichthyan braincase from the Early Devonian of South Africa. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 21(4), 702 - 713.

- Erin Maxwell, Heinz Furrer, Marcello Sanchez-Villagra, (2013) Exceptional fossil preservation demonstrates a new mode of axial skeleton elongation in early ray-finned fishes. Nature Communications 4(2570).

- Bernd Pelster (2021) MUsing the swimbladder as a respiratory organ and/or a buoyancy structure—Benefits and consequences. Journal of experimental Zoology Part A 335(9-10):831-842.

- Lauren Salien. (2014) Major issues in the origins of ray-finned fish (Actinopterygii) biodiversity. Biological Reviews.

- Hans-Peter Schultze. (1993) Patterns of diversity in the skulls of jawed fishes. In: The Skull, Vol 2. J. Hanken and B. K. Hall eds. pp. 189-254. Chicago, University of Chicago Press.

- Yoshitaka Tanaka, Hiroki Miura, Koji Tamura and Gembu Abe. 2022. Morphological evolution and diversity of pectoral fin skeletons in teleosts. Zoological Letters 8: 13.

- Conrad D. Wilson, Chris F. Mansky and Jason S. Anderson. 2021. A platysomid occurrence from the Tournaisian of Nova Scotia. Scientific Reports volume 11: 8375.

- Guang-Hui Xu and Ke-Qin Gao. 2011. A new scanilepiform from the Lower Triassic of northern Gansu Province, China, and phylogenetic relationships of non-teleostean Actinopterygii. Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society, 161, pp. 595-612.

- Guang-Hui Xu, Ke-Qin Gao, and John Finarelli. 2014. A revision of the Middle Triassic scanifepiform fish Fukangichthys longidorsalis from Xinjiang, China, with comments on the phylogeny of the Actinopteri. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology, 34(4), pp. 747-759.

- Min Zhu, Wenjin Zhao, Liantao Jia, Jing Lu, Tuo Qiao, and Qingming Qu (2009) The oldest articulated osteichthyan reveals mosaic gnathostome characters Nature 458, 469-474.

- Min Zhu , Xiaobo Yu, Brian Choo, Qingming Qu, Liantao Jia, Wenjin Zhao, Tuo Qiao, Jing Lu (2012) Fossil Fishes from China Provide First Evidence of Dermal Pelvic Girdles in Osteichthyans. Plos|one, April 3 2012.

- Min Zhu, Xiaobo Yu, Per Erik Ahlberg, Brian Choo, Jing Lu, Tuo Qiao, Qingming Qu, Wenjin Zhao, Liantao Jia, Henning Blom & You'an Zhu (2013) The braincase and jaws of a Devonian "acanthodian" and modern gnathostome origins Nature 502, 188–193.

- Hector Botella, Henning Blom, Markus Dorka, Per Erik Ahlberg & Philippe Janvier (2007) Jaws and teeth of the earliest bony fishes. Nature 448, 583-586.