Among the most rapidly evolving parts of the genome are those parts dealing with sex And resistance to disease. Thus, sex should be a good thing to look at for real world examples of evolutionary forces at work. But....

Among the most rapidly evolving parts of the genome are those parts dealing with sex And resistance to disease. Thus, sex should be a good thing to look at for real world examples of evolutionary forces at work. But....

Q: What is sex, exactly?

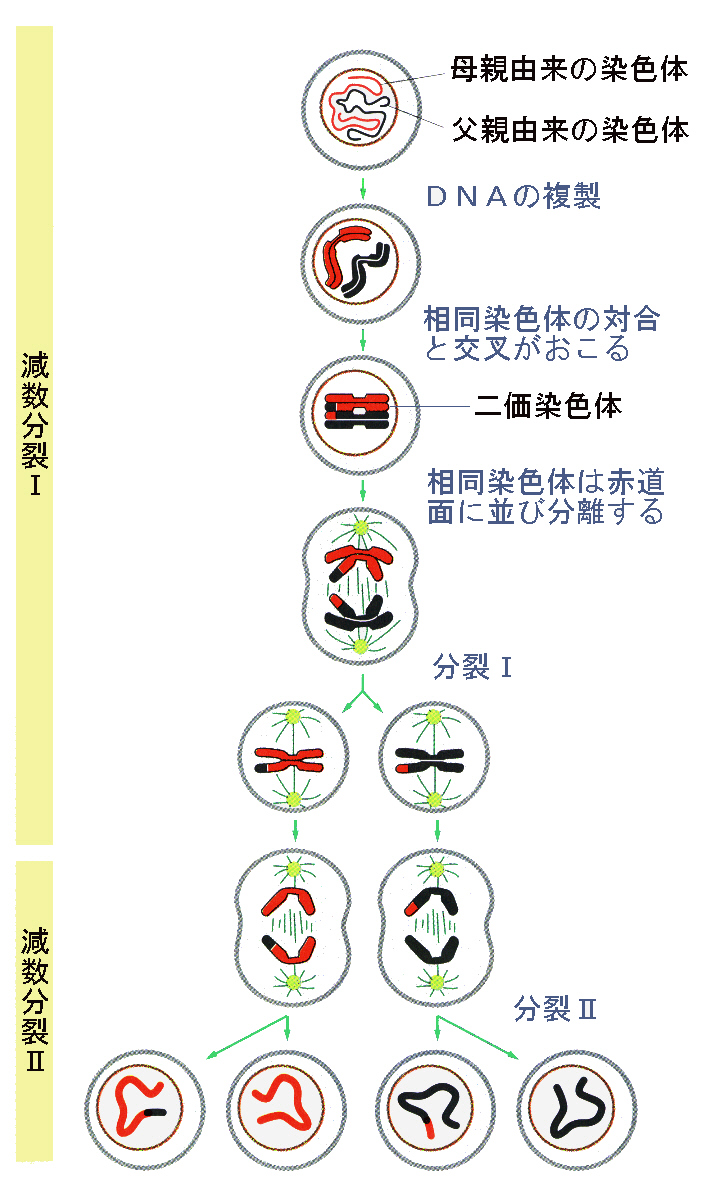

Gametes: Remember meiosis, the process by which gametes are generated. Genetic recombination is facilitated by:

- Crossing over

- Separation of homologous chromosomes.

- Diploid body cells contain two versions of each chromosome (one from each parent)

- Haploid gametes containing one version of each chromosome

- Independent assortment of chromosomes: In the new generation, chromosomes from one parent can be dissociated from one another.

Plasmids: This arrangement didn't appear overnight, but precursors are apparant. Prokaryotes (E. G. bacteria) which lack distinct chromosomes nevertheless recombine genes by swapping plasmids, small loops of DNA. This fact:

- Enables them to share genes that confer increased fitness

- Necessitates great care in the judicious use of antibiotics

Q: What is the evolutionary benefit of sex?

Asexual reproduction: Any gardener knows that many species can reproduce asexually, budding off pieces of themselves that grow into a new organism. That's a good "quick and dirty" method of establishing a population from a single pioneer. Yet almost no species completely forgoes sex. Those very few who do, including complex animals like several "species" of whiptail lizard, show why this is a poor approach.

Such parthenogenic species occasionally result from hybridizations and accidents in meiosis in which females end up with more than two sets of homologous chromosomes. These can sometimes reproduce parthenogenically (i.e. asexually), yielding clones of themselves.

Easy enough, but there are two hassles:

- The parthenogenic ratchet. Deleterious mutations simply accumulate and cannot be selected out of the population by recombination.

- The red queen effect. Remember the character from Through the Looking Glass who claimed, "[I]t takes all the running you can do, to keep in the same place." In nature, organisms must keep evolving in order to maintain the same level of fitness because their environment is constantly changing around them. The biggest component of that change seems to involve the evolution of disease pathogens.

Indeed, the lizards' need to engage in pseudocopulation in order to ovulate reveals their fundamentally sexual nature. Even what looked like textbook examples of parthenogenic species have recently been shown to sex after all. Consider the virginal shrimp Vestalenula.

The current asexual champs are Bdelloid rotifers, which seem to have gone without for the last forty million years. We'll see. Recent research indicates that bdelloids can possibly get away with asexuality because of a unique adaptation for dealing with disease pathogens.

The advantages of sex:

The advantages of sex:- Through sexual recombination of genes, it is possible harmlessly to remove a harmful allele from a population.

- Resistance to rapidly evolving disease and parasites can be evolved rapidly through recombination of alleles.

- Parthenogenic species are all clones of their founding ancestress. In a population, it's good to have variation, so that in case of a selective challenge, someone will have the genes to meet it.

- In social organisms, we can take this one step further. The group may depend on its members having a variety of diverse abilities. E.g.:

- New World monkeys tend to show several variants of color vision abilities in a single troop. Thus different individuals are adapted to seeing different food sources or predator camoflague.

- Among land snails, individuals of a single species often have a wide range of color patterns, preventing predators from developing a search image for members of an entire population.

Q: Why are we male and female?

Complex species with three or more genders remain the domain of SciFi, however there are many unicellular organisms:

- without physically distinct sexual morphs

- with large numbers of physically similar "mating types."

- with complex life cycles in which haploid and diploid stages alternate. Dinoflagellates may spend many generations as haploid "schizonts" that occasionally fuse to form diploid "zygotes" which in turn give rise to schizonts.

- The nurturing approach - Make a big, fat gamete with plenty of nutrients to support the new organism.

- The sneaky approach - Make lots of minimalist gametes with DNA, flagella for moving around, and just enough cytoplasm to support them.

Why this is so is not absolutely clear. It might be to manage the transmission of cytoplasmic components of the genome. (After all, if you got genetically dissimilar versions of the organelles with their own genomes like mitochondria from both parents, they might waste time competing rather than doing their jobs.)

Nevertheless, if you make ova, you are female. If you make sperm, you are male. NOTE: These are NOT mutually exclusive catagories. Creatures may be:

Nevertheless, if you make ova, you are female. If you make sperm, you are male. NOTE: These are NOT mutually exclusive catagories. Creatures may be:

- dioecious - either male or female

- hermaphroditic - both at once

- Some switch genders during their lifetimes. Clown fish (right) start male and become female. Parrotfish start male or female and become male.

Every organism has one evolutionary goal: to maximize the representation of its genes in the next generation.

How one goes about that varies greatly between species and between genders in a species. Despite their great diversity, one great pattern emerges from organismal sex practices:

The battle of the sexes.

You would think that by "putting all their gametes in one basket," males and females would have an incentive for complete cooperation, but this is not so. In fact, males and females each have their own agendas that can, at times, be so divergent that they actively sabotage one another. The paradox of sex (from an evolutionary sense, at least) is that while it requires intimate cooperation with another individual, it is utterly selfish.

Q: What is the female agenda?

With a more limited number of gametes, maximum fitness comes from optimizing the survival chances for each ovum. That typically means:

- Choosing the fittest mates to maximize individual offspring's potential fitness.

- Maximizing the genetic diversity of offspring (i.e. having multiple mates) to insure that at least some offspring will be able to cope with any of a broad range of challenges.

Q: What is the male agenda?

With a lots of gametes to spread around, maximum fitness comes from maximizing the number of ova fertilized. That typically means:

- Having many mates to maximize the number of offspring.

- Maximizing the number of any given mate's ova that you fertilize to maximize the number of offspring.

Other issues: Of course, the "battle of the sexes" is constrained and moderated by:

- demands of the physical environment

- the idiosyncracies of one's heritage and the equipment with which one is born.

The female strategy

Maximizing one's female fitness - being the optimal nurturer - requires:

- Matching one's reproductive strategy to the limits of the environment:

- If the environment is so abundant that you can't possibly overtax it with your offspring, the limiting factor is reproductive rate. You are R-selected,

- If the carrying capacity of the environment is the limiting factor,you are K-selected.

- To obtain good genes for making fit offspring

- In cases requiring prolonged care of offspring, selection of a reliable partner to maximize offspring's survival

- Avoidance of disastrous mate choices:

- wrong species resulting in relatively unfit hyprids.

- Very close kin resulting in more likely expression of deleterious recessive genes.

These choices can be heavily weighted by peculiarities of

- Reproductive systems

- Environment

Reproductive systems: You will be familiar with sexual selection in the form of conscious female mate choice, but it can also happen cryptically. E.G.:

Reproductive systems: You will be familiar with sexual selection in the form of conscious female mate choice, but it can also happen cryptically. E.G.:

- Ancestrally, birds ancestrally lost their penises. Among ducks, however, forced copulation (rape) is common. Female ducks have developed elaborate elongate oviducts by which they trap and expel the semen of undesirable partners. Males, in repsonse have (re)evolved truly magnificent elongate phalluses (right) meant to convey their semen safely through the female obstacle-course.

- When the female's reproductive system evolves into an obstacle course that only admits the fittest sperm, as in Drosophila bifurcata, where size of the sperm cell confers greater success. In this case, the female's choice, although absolutely real, is unconscious.

Environmental pressure: For the fig wasp, the environment is utterly hostile and barren unless you live in a fig, in which case it's like paradise. You can't find a mate unless you're in a fig, so it's worth it to stick with your fig, even at the risk of mating with your siblings who are likely to be the only ones around. In fact, insects like wasps, bees, and ants, practice haplodiploidy, a genetic mating system that minimizes the hazards of in-breeding. In haplodiploid animals, males are haploid, thus, any deleterious recessive gene is automatically phenotypically expressed, resulting in its quick removal from the gene pool. (See below)

Environmental pressure: For the fig wasp, the environment is utterly hostile and barren unless you live in a fig, in which case it's like paradise. You can't find a mate unless you're in a fig, so it's worth it to stick with your fig, even at the risk of mating with your siblings who are likely to be the only ones around. In fact, insects like wasps, bees, and ants, practice haplodiploidy, a genetic mating system that minimizes the hazards of in-breeding. In haplodiploid animals, males are haploid, thus, any deleterious recessive gene is automatically phenotypically expressed, resulting in its quick removal from the gene pool. (See below)

The male strategy

A typical male dilemna: Ideally, a male would seek to mate with as many females as possible and, hopfully, exclude his rivals from so doing. But the problem: in most species, the female plumbing is arranged such that the last male to mate with her is the most likely to father her offspring. Strategies to deal with this include:

- Mate guarding after mating, to deter the attention of other males. This can easily be observed in dragonflies and damselflies.

On the other hand, the male will lose interest once the female starts to lay eggs and will zoom off in search of other females, thus optimizing his chances.

- Sperm removal in which competitors' sperm is removed from the female system prior to mating. E.G.: Cephalopod males mate by using a special arm to deposit packets of sperm (spermatophores) inside the female's mantle cavity. In some species, we see elaborate "cleanup" stages of courtship, prior to mating.

- The "Sherwin Williams" approach In many species, especially those that mate frequently and promiscuously, one way to optimize the fitness of matings is simply to produce more viable sperm than the competition. For example:

- Testicle size in chimpanzees vs humans

- Sperm conjugation in Marsupials

More

Maximizing coverage can lead to novel strategies.

Maximizing coverage can lead to novel strategies.

Shortcuts: Among hemipteran insects (true bugs) sperm is normally held by the female in a sperm reservoir until it is needed for fertilization of ova. The male's incentive is to bypass this obstacle and get his sperm as close as possible to the ovaries during mating. The bedbug Cimex lectularius achieves this by the extreme method of "traumatic copulation" in which the male ignores the female's genital opening and simply punches a hole in her abdominal wall and releases semen into her body cavity. Any sperm reaching the ovaries result in fertilization.

Variations

Q: Monogamy: Why would anyone limit themselves to a single mate?

Definitely not the norm no matter how much we, for cultural reasons, want it to be. Why would members of either sex forego access to multiple partners? Indeed, the spread of genetic testing has shattered our illusions about many species formerly thought to be monogamous. Seems that most even those that pair up for life as a social arrangement frequently sneak around when it comes to actual mating. But true monogamy happens in some unusual circumstances.

Danger: The male dragonfly has it easy in that there are typically plenty of females around to fight for. In some environments, potential mates are so rare, and the environment so hostile that one's chances of ever finding one mate before dying are not good. If you're lucky enough to find a mate, better to stick with him/her rather than risk dying alone. An extreme expression of this is in deep-sea angler fish, in which the male, in effect, becomes part of the female's body. The ultimate must be the Australian red-backed spider, whose male deliberately somersaults himself onto his mate's fangs, allowing her to start eating him while he is still busy copulating. (Male preying mantises, of whom we hear much, at least try to get away.)

Danger: The male dragonfly has it easy in that there are typically plenty of females around to fight for. In some environments, potential mates are so rare, and the environment so hostile that one's chances of ever finding one mate before dying are not good. If you're lucky enough to find a mate, better to stick with him/her rather than risk dying alone. An extreme expression of this is in deep-sea angler fish, in which the male, in effect, becomes part of the female's body. The ultimate must be the Australian red-backed spider, whose male deliberately somersaults himself onto his mate's fangs, allowing her to start eating him while he is still busy copulating. (Male preying mantises, of whom we hear much, at least try to get away.)

More

Q: Hermaphrodites: Why not give everyone the option of being male or female?

Maybe the key to ending the war of the sexes is to give everyone the same equipment? Alas, no. Although there are many species of cross-fertilizing hermaphrodites in which each individual simultaneously uses both male and female systems, the matings of hermaphrodites are often downright violent. E.G.:

Maybe the key to ending the war of the sexes is to give everyone the same equipment? Alas, no. Although there are many species of cross-fertilizing hermaphrodites in which each individual simultaneously uses both male and female systems, the matings of hermaphrodites are often downright violent. E.G.:

Among the more extreme expressions of hermaphrodite violence, Marine flatworms must fight over who gets to inseminate whom with caustic, ulcer-producing semen. The "loser" has to be the "girl," but at least "she" has made "her" mate pass a qualifying exam - a form of female choice.

Snails routinely jab one another during mating with darts covered with pheromones that stimulate the recipient's female system.

Snails routinely jab one another during mating with darts covered with pheromones that stimulate the recipient's female system.

Maybe it's easier to be born knowing who gets to be the boy and who gets to be the girl and who's a potential mate and who's a potential rival without having to fight over it.

Q: Abstinence: Why would anyone evolve to not reproduce?

What would make a female evolve to be infertile? That's what happens in a handful of eusocial animals - those that live in complex societies in which most individuals are non-reproductive workers. Examples include:

- Blind naked mole-rats

- Termites

- A handful of isolated arthropods (spiders, ambrosia beetles, aphids)

- Many separate origins in the insect order Hymenoptera including wasps, bees, and ants.

Why hymenopterans? They are the ones who practice haplodiploidy, in which fertileized ova develop into diploid females and infertile ones develop into haploid males. (Remember the fig wasps) You need to track where genes are coming from and who is most closely related to whom.

Human (either gender)

| % of your genes shared (maternal) | % of your genes shared (paternal) | % of your genes shared (total) | |

| Mom | 50% | 0% | 50% |

| Dad | 0% | 50% | 50% |

| Sister | approx. 25% | approx. 25% | approx. 50% |

| Brother | approx. 25% | approx. 25% | approx. 50% |

| Child | - | - | 50% |

Hymenopteran female

| % of your genes shared (maternal) | % of your genes shared (paternal) | % of your genes shared (total) | |

| Mom | 50% | 0% | 50% |

| Dad | 0% | 50% | 50% |

| Sister | approx. 25% | 50% | approx. 75% |

| Brother | approx. 25% | 0% | approx. 25% |

| Child | - | - | 50% |

The result: Whereas a female shares 50 percent of her genes with her mother, she shares, on average, 75 percent with her sister. Thus, to maximize the representation of her genes in the next generation, her best strategy is to farm mom for more sisters.

Obviously this is not the only reason for eusociality (otherwise creatures with normal diploid genotypes would not evolve it) but it probably explains the preponderance of eusocial hymenopterans.