Key Concepts: Climate change deniers are not the only ones who share misinformation about the scientific issues of global climate change, the biodiversity crisis, or related issues. Many people concerned about this topics spread factually-incorrect ideas (including, sadly, some non-profit organizations and professional scientists!) Remember to keep informed about the actual Science behind the issues.

We are already used to seeing, and addressing, incorrect truth claims about climate change proposed by climate change deniers. Normally these are used (as we have seen) to justify inaction (or more generally, maintaining "business-as-usual") on issues concerning reduction of greenhouse gas emissions and natural resources management.

That said, incorrect statements about global change issues are not solely created and spread by denialists. Many climate change activists and even environmental science faculty promote ideas which are incorrect (either entirely or partially.) Some of these simply represent out-of-date information which has since been overturned due to new discoveries and analyses. In others there are particular political or social motives behind the arguments exclusive of (and at least partially contradicted by) Science. Sometimes these are taught in classes; other times (perhaps the more common mode) they are spread on social media. (I myself have seen all of these promoted on Facebook and Twitter memes, and at least one was a TikTok video shared on Twitter...).

As with at least some denialist claims, there is often a grain of truth behind them, and in fact in some cases more than a grain. But they fail to capture the big picture, and so should be addressed.

Case Study 1: Half (or more) of our oxygen comes from the sea

This is one that is very widespread and is definitely taught in some classes on campus! It's origins are very sensible: the majority of the Earth's surface are (~70%) is ocean; algae inhabits the upper layer of the water (phytoplankton in the photic zone); and thus you might expect that half or more of the oxygen in the atmosphere (which is produced via photosynthesis) should be from the ocean.

This is however based on the premise that a given surface are of water produces as much oxygen via photosynthesis as the same surface area on land. This is demonstrably false. The amount of biomass (living matter) of algae is very small compared to the amount of biomass of land plants: in a 2016 study it was found that land plants make up about 450 Gt of carbon, of which 135 Gt represents "green" biomass (as opposed to twigs, stems, roots, etc.). In contrast marine algae consists of less than 1.3 Gt of cyanobacteria and 0.1-0.3 Gt of eukaryotic phytoplankton (diatoms and the like.) So there is nearly 100 times as much photosynthetic land plant biomass as there is marine equivalent.

This actually shouldn't be so much of a surprise. Consider how much of the land surface you can walk around (whether cultivated or wild) has green plants around, and now think of how clear most sea water is.

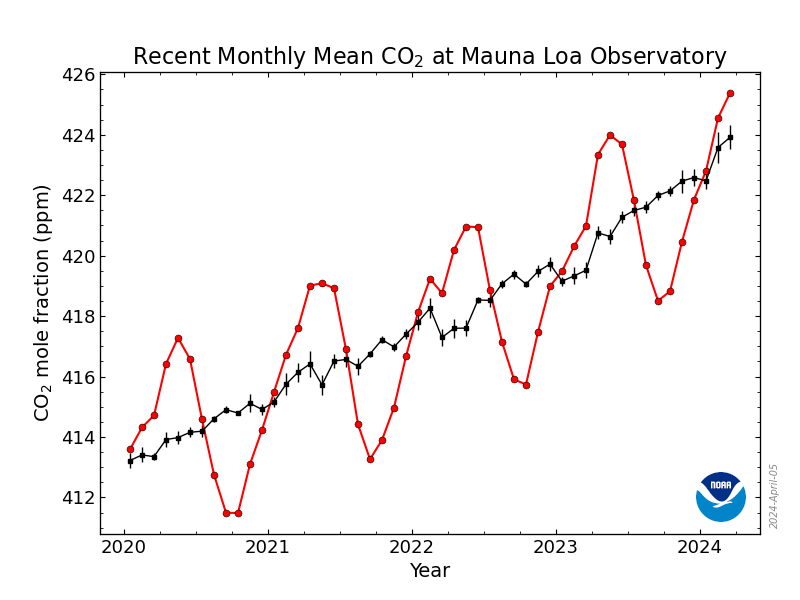

Climate change scientists--and people who care about climate change issues--should have been more aware of this fact, because without it one of the most iconic images of the field wouldn't make sense!! After all, consider the Keeling Curve:

As we discussed last year the annual down and up cycle of carbon dioxide reflects the uptake of CO2 during Northern Hemisphere late Spring-to-early Fall vs. the release due to decay during Northern Hemisphere late Fall-to-early Spring. Why should the Northern Hemisphere dominate? If the oceans were as productive in oxygen as land than the ocean-dominated Southern Hemisphere should balance out the land-dominated Northern Hemisphere, and there shouldn't be such cyclicity. But because in reality there is vastly more photosynthetic activity on land than at sea, the Keeling Curve shows a Northern-dominant pattern.

(Less obvious to the average climate change worker, but well-known to geologists and paleontologists, the evidence shows a dramatic increase (perhaps 10-fold!) in the amount of atmospheric oxygen with the rise of vascular land plants in the mid-Paleozoic Era.)

So the status of this one is that it is simply out-of-date. Don't repeat it. And honestly, if you have an instructor, family member, or friend who does repeat this, please send them the URL to these lecture notes.

Case Study 2: Wind turbines shouldn't be used, because it kills lots of birds

Of all the items on this list, this is problem the one that I personally heard first and most often. It does stem from a real observations: birds do wind up getting killed on occasion by wind turbines. As a bird-fan this is personally distressing. And indeed I suspect some of the outrage against the use of wind turbines is in fact anger at the loss of our feathered friends. (However, I also suspect at least some who make this argument are either invested in the fossil fuel industry or (sadly) want green power but don't want it in their backyard, so they bring this up at meetings and panels so that the zoning permits for new wind farms near their property are not approved...)

What is the truth? The truth is that yes, turbines kill a lot of birds. They are not the MAIN killer of birds, however. As this often-repeated graphic shows, in the US wind turbines kill far fewer wild birds than many other sources, and are orders of magnitude less deadly than cats, buildings, or collisions with vehicles:

(An update: this graphic shows a mid-point in the estimated number of building-related deaths for birds, which might actually be as high as a billion birds per annum!) (And literally two seconds after I typed this, a bird flew into the window near my desk! Thankfully, it seems to be okay...)

As it turns out, there are things we can do to make wind turbines less deadly to birds. Most importantly is proper siting: in particular, try not to place wind farms smack dab along major bird migratory flight paths or other known spots with great numbers of birds!! Additionally, an interesting (and cheap!) solution was recently described: by painting one of the turbine blades black, bird fatalities are reduced by over 70%!. And there may be other solutions to bring the numbers down further.

And all of this misses the big picture: a greater threat to bird populations (and other species...) than any of these listed in the graphic above is the environmental impacts of global climate change, particularly under "business-as-usual" models! Wind power will be an important part of green energy for the foreseeable future, from micro-turbines to big offshore wind farms. The reductions in carbon emissions from these will result in a far lower bird death rate than a 5 or more C

So this issue is overblown, can be mitigated by relatively simple solutions, and misses the large-scale environmental benefits of wind power.

Case Study 3: Human population size isn't a factor in environmental impact and biodiversity decline

This particular case often intertwines with case studies 5 and 6 below. We have observed that rates of extinction are higher and increasing over time (part of the whole "Sixth Extinction" event.) This has occurred at the same time as human population rates have also been increasing rapidly.

But you will find people who challenge a connection between the two, and who say that to say increasing human population results in biodiversity decline is racist and/or colonialist.

The reason for their arguments aren't entirely wrong. It is very true that the environmental impact per capita varies widely from nation-to-nation and economy-to-economy. Taking a look at per capita carbon emissions, for instance, we see that a small number of nations with small population size have grossly higher emissions than do many other nations:

(updated to reflect data to 2019):

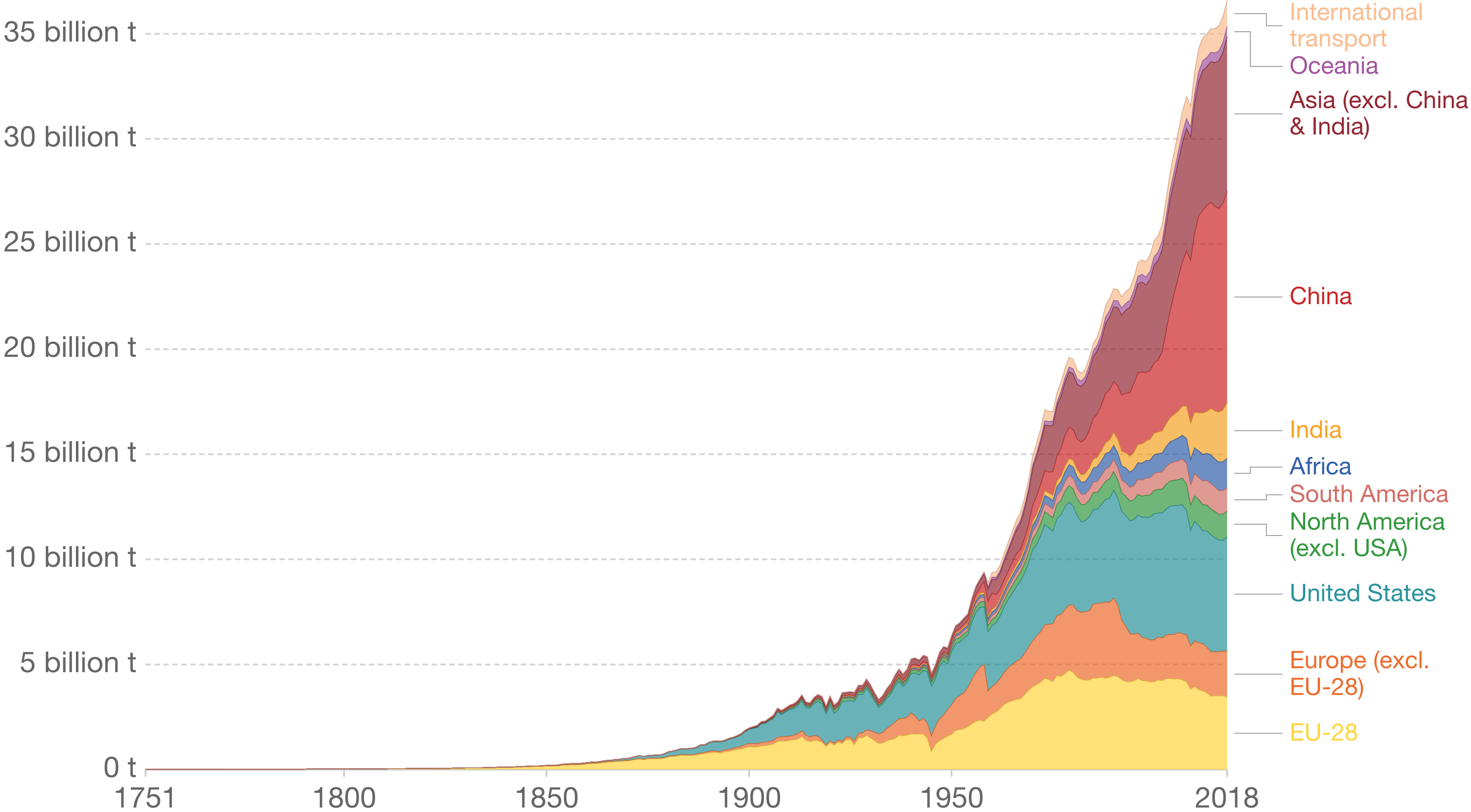

Or we can look at the change in total emissions by region over time:

So there is merit in pointing out that many populous countries are not as responsible for global change impact as the less-populous wealthy country. And indeed sometimes this discussion is held in response to a "blame the poor/the Global South" form of argumentation.

But Nature doesn't care about which humans are doing what. It is affected by our actions regardless of the distribution of which humans produce more impact than others. It doesn't know about our national boundaries and economic systems. In the end, human impact on the environment is about HUMAN impact: not Indian, Paraguayan, Nigerian, or whomever impact.

All humans everywhere need food, water, and space. If a human is accessing those calories, water, and area, than wildlife cannot be. An increase in human presence on this planet necessarily comes at the cost of other living beings. The overall pattern is clear: more humans on the planet result in increased rate of extinction of species (number extinct per year) in wildlife:

This issue is a complex one rather than a matter of being wrong or overblown. It is definitely true that per capita some nations and lifestyles have a vastly bigger impact than others. As we have been exploring the last two semesters, there are many aspects to industrialized consumer-based economies that are tremendously detrimental to the environment, and must be reduced and transformed to more sustainable systems.

But it is a basic aspect of ecology that resources of a given area per unit time are limited: if humans are using these resources (to eat, drink, and occupy space) than a comparable amount of wildlife biomass cannot. This would also be true is you replaced "humans" with "koalas", "kudzu", or any other species. This isn't a simplistic "human bad, wildlife good" type issue; it is a matter of limited energy flow in a system. So it is best to say that the issue is nuanced but told in a way to be misleading. We do have to consider the impact of a net increase in total human occupancy of this limited planet, just as we need to consider how to reduce each human's impact based on our lifestyles. It isn't a matter of just one or just the other.

This Just In (Clark et al. 2020, published on 6 November 2020): emissions from the global food production system as currently structured make it impossible to limit global warming to 1.5

Case Study 4: Just 20 (or 50 or 100) corporations are responsible for most of carbon emissions

Honestly, this one is used as a blame-shifting argument to allow people to still live in an industrial resource-extractive society and still feel good about themselves. "It's not my fault; it's the fault of the megacorporations. Nothing I do will affect this."

The general observation is this: there is a small number of corporations (since people like nice round numbers, the article or meme normally formulates it as "20 corporations" or "50" or "100"). Here is one such article.

The idea isn't technically incorrect. It is true that a small number of corporations account for the vast majority of fossil fuels pulled out of the crust. But here's what people who post this meme fail to consider: Chevron and ExxonMobil and BP and so on are NOT the ones using the petroleum. They aren't making the emissions. We--the citizens of the world--are. We do so directly (by driving cars, taking trains, flying in planes), and indirectly (by buying goods that are transported minimally from the factory to the store, and these days also from the distribution center to our home; by buying food that was farmed using machinery and also transported from form to store.) It isn't that Shell has a center somewhere that is just burning the gasoline they extract away: that isn't at all how their business model works.

There are plenty of issues to hold the petrochemical companies and their coal-mining equivalents accountable for with regards to climate change: suppressing early discoveries of the potential impact of their product; funding climate change denialism in the media; lobbying politicians all over the world to give them subsidies so that they compete with unfair advantages against other energy sources, etc. But they are NOT the ones who are creating the emissions. If there wasn't a market for it, they wouldn't be as big business as they are.

So this idea is a blame-shift argument. In the end it is up to the citizens of the world to support other forms of energy generation, modes of transportation, and so forth, and to support the politicians, non-profits, and even corporations that will promote more sustainable and less detrimental technologies.

Case Study 5: It's all capitalism's fault

This idea is entwined with the next one, as well as the previous two. It is unquestionable that consumer capitalism (i.e., the one we are used to in the modern age, as opposed to the early days of the Industrial Revolution which saw little increase in the availability of goods or services to the working class) has been grossly detrimental to the environment. as practiced it focuses on extractive technologies; it is predicated on the idea of planned obsolesce even for expensive items like computers or cars; operates on the assumption that people will always want more/better versions of whatever they have; and (at least traditionally) assumes that once you have used up your products that you throw it "away". Furthermore, as we saw last semester, traditional economics fails to account for the externalities related to the extraction, use, and disposal of resources, so that they are not included in the pricing or taxing of these.

But to blame all of the environmental impact of humanity of capitalism, or to use the logical fallacy that if capitalism has a bad impact on the environment that other systems must be better, is short-sighted. Some look to indigenous ways of living: we will see about some of these issues in the next case study, but I think it is fairly clear that for the near term it would be unlikely for the majority of people in the industrialized world to suddenly adopt indigenous lifeways. The main alternative people look to is socialism, and here we find this case study is grossly flawed.

One the one hand some look to the generally good (or at least not horrible) environmental records of democratic socialist societies as in Scandinavia and elsewhere. However, this is a conflation of two different issues! While in terms of government responsibility for social institutions these nations are "socialist" compared to the US or Australia or the like, the market economies there are just as consumer capitalist as here. The shops have a wide variety of products from different companies (typically the same ones selling in the US, the UK, and so on); people are buying the latest Nokia phone; and so forth. So for the purposes of the factors which impact the environment these are still capitalist countries.

In contrast, the record of authentically socialist (in fact, communist) market countries with controlled economies upon their environments has been historically dismal, often as bad or worse than capitalistic countries of the same time. While the early days of socialist revolutions thought that a planned economy would avoid the excesses of the West (and in many ways it did), much of the rest of their environmental history was quite bad. The Soviet Union, the People's Republic of China, and their various client states had notoriously high rates of pollution (both near population centers and in the wilderness). Large scale operations dictated from their central committees (from the draining of the Aral Sea to China's ill-fated attempt to exterminate sparrows) were typically done without input from relevant scientists. And in general the assumption that the plans from central authority would be correct because they came from the central authority failed, as Nature doesn't care whether an idea follows proper Marxist doctrine or not.

Ultimately the horrible environmental record of the socialist/communist economies stemmed from the fact they occurred within dictatorships. Elsewhere private citizens, non-profit organizations, and opposition party politicians could speak up against environmental malpractice, and the possibility of goods or services with reduced environmental impact allowed consumers to "vote with their pocketbook". In one-party states with planned markets, these were very difficult for concerned citizens to do. Furthermore, with state control of the press it was difficult for many people to even be informed of the problem even if there was one.

(Castro's Cuba was an exception that proves the case. Although the Cuban Communist Party held similar control of the government, markets, and press in his nation, Fidel Castro personally was interested in environmental matters and wanted to preserve more of the wildlife of his nation against the degradations that was going on elsewhere in the Caribbean. An environmentalist dictator can certainly do more for the environment than an environmentally-oriented leader without as absolute authority... As a consequence, Cuba's wildlife is among the best protected in the region.)

As Dr. Merck discussed last semester, new forms of economics (even within a capitalist structure) could be revised to be more responsive to climate change issues. Pricing, taxation, and other revised economics that included the value of ecosystem services have the potential to reduce our environmental impact. And already at least some companies and industries have seen the benefit of recycling/repurposing materials to be less extractive.

So this meme has a lot of truth in it, in that extractive consumer capitalism is environmentally destructive. But it is incomplete. A market in which environmental impact has a feedback role onto production and consumption, and a society where the leaders (political, social, and economic) can be held responsible by its citizens is more likely to be restructured into sustainability and resilience than one which is not.

Case Study 6: Indigenous rule would end climate change and biodiversity decline

A memetic idea current on social media is responding to someone who claims "humans are responsible for climate change/environmental decline" by pointing out that indigenous controlled lands are where 80% of biodiversity remains. So it isn't humans that is responsible; it is consumerism/industrialism.

In broad strokes there is nothing incorrect about this. After all, we've seen that was the industrialized use of fossil fuels that led to anthropogenic global warming, and extractive use of natural resources in general that is responsible for overall environmental impact. These are byproducts of the industrialized world.

Furthermore, it is true (as we saw in Drawdown that various indigenous forms of land management are far more sustainable than standard commercial systems. This makes sense: any system that has existed for millennia is by definition relatively sustainable on human time scales.

We saw in the first semester that human arrival into places not previously occupied by people often resulted in the local extinctions of animals and plants, especially large-bodied animals. This pattern was seen from Pleistocene Australia and the New World to the Pacific, Madagascar, and New Zealand during the last 2000 years. But typically as these arriving humans move from invasive species to what would later be called "indigenous" populations they developed lifeways that could persist for very long periods of times. That isn't to say that such peoples are "at one with Nature" (as some well-intentioned but essentially racist folk from industrial societies would think), but rather that through trial and experiment traditional practices were developed that were successful over the long term.

There are two main misleading aspect to this meme. The first is a pragmatic one: how useful is this observation? Would it be at all possible for American or British or Japanese or Kenyan citizens to abandon cities and suburbs and start life in an indigenous style? And what would that lifestyle be? There is no one "indigenous" way of life: it is adapted to local climate, resources, environment, and so forth. Furthermore indigenous forms of food production provide too little nutrients per unit area to feed the global population; such an abandonment of urban life would require the death of a sizable fraction of our species.

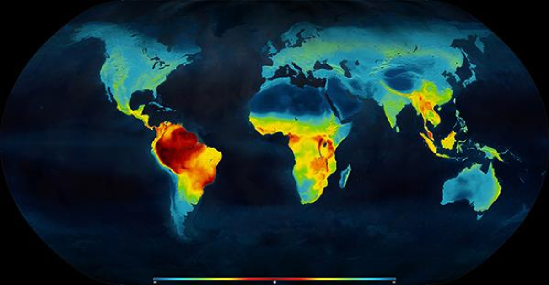

Another misleading aspect of this meme is the issue of biodiversity. It is true that a huge amount of biodiversity is found in indigenous-held land, but this isn't precisely due to better land management. Instead this is a byproduct of the fact that biodiversity in the form of number of species per unit area is not uniform or randomly distributed over the surface of the Earth. A long-known feature of ecology is the latitudinal gradient of biodiversity, with there being vastly more species living in the tropics than higher latitudes, and vastly more species in rainforests than elsewhere. In the map below the hotter color reflects higher species diversity:

This pattern is not new: it extends back in geologic time long before the rise of humans. Ecologists still debate the exact cause of it (more favorable conditions for originations?; smaller species ranges in tropical organisms?; etc.), but this pattern is real and external to humans.

Indigenous peoples make up only about 6% of human populations. And while they can claim customary ownership for a larger fraction of the surface of the planet, in practice they have direct "tenure secure" ownership of about 10% of this. As one might image, the regions that are given over to indigenous tenure have historically been those lands that settler powers find less profitable. One such environment has historically been tropical rain forests. So due to this lands being (until recently) perceived as non-profitable, the environment that has large numbers of rare species are mostly in the hands of indigenous population: hence the "80% of biodiversity" figure.

(Related to this is the issue of biodiversity being measured in "number of species" rather than in "biomass". That 80% of species mostly consists of species with very small population sizes and habitat areas.)

All that said, protecting biodiversity (even, or maybe even especially, of rare species!) is most definitely a goal to be achieved, and indigenous tenure of the lands with these species is the means by which this can be achieved. Furthermore, even if specific practices of indigenous land management might not be exportable to different climes, the knowledge and experience can inform new thinking about practices elsewhere. And finally allowing cultures to maintain their traditions--and especially to protect their land ownership from industries that are now exploiting rainforests at an ever-increasing rate, as in the Amazon and in Indonesia--is a just and worthy effort.

So this meme is a little misleading and not particularly actionable, but at least it has the potential to alert a larger public to a series of important issues.

Closing Thoughts

It can often be difficult to convey your thoughts and ideas effectively, particularly when they require a fair amount of background material. Thus, we often rely on memetic shorthands to spread concepts we feel are important, valid, and significant. But please do so with care, and try not to spread misinformation when you are trying to get helpful ideas to your fellow citizens.