Joh Fredersen confronts Dr. C. A. Rotwang and his creation

in Fritz Lang's Metropolis (1927) from Growing Branch

Science can contain many kinds of mistakes and still be proper science. Indeed, the whole point of the scientific method is to assume that mistakes happen, and to identify them.

Pseudoscience, in contrast, involves some perversion of the scientific method. This can include:

- subconscious self-deception

- deliberate fraud

- naive non-comprehension of the method

Is pseudoscience even a fitting topic for a university lecture? After all, Antarctic Hollow-Earth Space Nazis seem so obviously bogus. The problem comes when pseudoscience is sophisticated enough to slip past us and become lodged in culture and policy. And that brings us to..

The cultural idea of the evil mad-scientist.

We all know the stereotype: Evil scientists:

- In fiction: Dangerous megalomaniacs playing recklessly in God's domain. Dangerous threats to social order and safety.

- In folklore: Researchers and organizations (often with dark, antisocial agendas) whose activities purport to be scientific but are grotesquely immoral in their implementation, whether methodologically proper or not.

- In reality: ?????

But note: Whatever they are, they represent a range of activities that span the spectrum from pseudoscience to proper science.

So, where does our fear and fascination with evil science come from?

1.) People are Intimidated by Science

Q.: If the real science is so fundamentally honest and pseudoscience dishonest, why does popular culture so frequently regard real science with suspicion and embrace the "bold iconoclasts" and "free thinkers" of pseudoscience?

- The scary factor - Science's power in daily life: Most people don't really know what scientists do, but they DO know that the products of scientific activity, the technologies that science spawns, have huge impacts on their lives:

- Some of these are beneficial: Medicine, electronic devices, agricultural productivity.

- Some are threatening: Hydrogen bombs, nerve gas, global warming.

- Unpleasant realities: Even when they have no practical impact, scientific ideas have a way of confusing us or deflating our egos:

- Heliocentric Astronomy - (Humans not physical center of Universe)

- Deep Time - (Human history only a brief blip in a huge pre-human epic.)

- Evolution - (Humans share common ancestry with non-human creatures.)

- The Big-Bang Theory of cosmology - (The Universe isn't eternal)

- Vast conspiracies: We tend to be suspicious of the motives of big mysterious institutions (like the NIH or NSF), whereas bold iconoclastic individuals with no institutional affiliation and nothing to lose or hide (like many pseudoscientists) at least seem candid and up-front.

- Wanting to belong = wanting to believe: Organizations promoting pseudoscience tend to provide non-specialists with avenues of social affiliation and a sense of belonging to something important.

- Easier than thinking: Finally, frankly, most people are intellectually lazy. The concepts of pseudoscience can usually be summed up in atomized, appealing-sounding slogans. That's a lot more fun to learn and spout than the prerequisite-knowledge dependent, highly qualified, and often complex relationships of real science.

2.) Subconsciously, We Believe Fiction

Into that gulf of suspicion steps an entire range of folk culture including:

- Popular fiction

- Pseudoscience.

- The occasional piece of real science done very irresponsibly.

Fiction: Most people actually know that the individual mad scientists of fictional stories (C. W. Rotwang, Victor Frankenstein, etc.) are fictional characters, so each new addition to the genre has little effect, but the cumulative effect of constant exposure to the genre is profound, because subconsciously we assume that the specific fictional mad scientists are based on an underlying real phenomenon, just like the fictional Michael Corleone of The Godfather (right) was based on real gangsters.

The golem menaces the innocent Miriam in the 1920 film

Der Golem, wie er in die Welt kam - Carl Boese and Paul Wegener,

from garylucas

- The Golem: A wise man (usually a rabbi) creates a creature out of clay and gives it the semblance of life. The creature or Golem (Hebrew for "unformed matter") serves the rabbi and his community in various ways in different stories, but although it is valued and admired, it becomes more and more powerful, so that it eventually becomes threatening and has to be destroyed.

- Dr. Faustus: A scholar, dissatisfied with his achievements, makes pact with the devil trading his soul for the ability to achieve knowledge on Earth. Of course, his hubris leads him to ultimate damnation without achieving the things he desires. Made famous in plays by Christopher Marlowe and Johann Wolfgang von Goethe.

Of course, once modern science got going, artists and entertainers quickly siezed on people's fascination with it, weaving it into previous folklore.

- Frankenstein: Mary Shelley single-handedly invented the genre of science fiction with Frankenstein or the Modern Promethius, in which she "reimagined" the Golem and Faustus stories in the context of contemporary science - Luigi Galvani's discovery that the force animating muscle tissue is ordinary electricity. In her book, she sets the tone for later sci-fi "mad scientist" stereotypes, making Victor Frankenstein an irresponsible egotist who doesn't care about the well-being of his creation, a powerful yet helpless creature which, in turn, harms innocent people.

- Contemporary examples are legion.

3.) Social forces exploit the mad scientist myth:

Sometimes cynically to manipulate public sentiment, sometimes with misguided sincerity. (You may decide which motive is of greater concern.)

- Genetic research: Wouldn't it be a shame if society turned it's back on an opportunity to feed the world or cure terrible diseases because of our culturally engrained suspicion of malevolent "mad scientists" playing in God's domain caused us to abandon genetically altered crops? ("Frankenfood!")

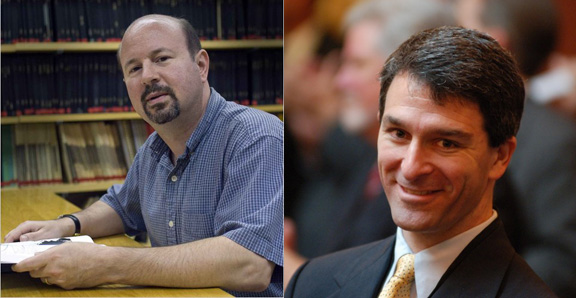

Climate Researcher Michael Mann and his nemesis, former VA attorney general Ken Cuccianelli - Climate change: For SGC, the issue is particularly acute, as climate-change deniers typically regard the overwhelming scientific acceptance of anthropogenic climate change as evidence of self-serving opportunism by climatologists, if not of a vast conspiracy by the scientific establishment. Indeed, in the 2016 election year, many candidates are unconvinced of the reality of climate change but at least one seemed, sincerely, to embrace this conspiracy theory. To him, at least, the evil scientist stereotype is based in reality, and academic establishments must harbor a whole professional class of pseudoscientific deceivers!. Had he been elected president, would his conscience not compel him to take action against these conspirators? (For the moment, President-Elect Trump seems to have backed away from his earlier denunciations.) In this context, the question of whether society is actually menaced by scientists takes on real gravity!

To recap, suspicion of science is:

- grounded in reasonable concern about science's power in society

- draws on long folkloric and literary tradition

- is amplified by entities seeking to exploit public fear.

So, do evil scientists threaten society or not? Just how careful does the public have to be about scientific ethics and the secret agendas that scientists might pursue? Are "mad scientists" a:

- Major and recurring threat to humanity?

- Mythical beast preoccupying only the superstitious?

- Something in between?

A Rogue's Gallery of Mad Scientists:

Trigger Alert! To explore this, we have a survey of candidates for the title of real-life mad scientist. Their careers can be shocking. We don't flinch from dangerously violent bad guys in movies, but when they actually walk among us, it is very disturbing. Indeed, a basic qualification for consideration as a mad scientist is that somewhere along the way, you rack up a body count. I note two broad categories:

- Pseudoscientists that manage to pass as the real thing

- Practitioners of methodologically proper science with defective moral compasses.

Here goes:

Pseudoscience kills:

My survey of real-life mad-scientists spans the spectrum from:

- Genuine pseudoscientists who managed to infiltrate proper scientific institutions. Proper scientists either let them into their establishments or couldn't prevent politicians or commercial interests from forcing them in.

- Methodologically proper scientists with defective moral compasses who took advantage of unusual social circumstances.

- Individuals combining characteristics of both.

Trofim Lysenko - Pseudoscientist (1898 - 1976):

- Background: Ongoing political theoretical conflict between mendelian genetics and lamarkianism.

- 1927: Publication of "vernalization" the idea that plant development is a function of environment at different life stages (an idea with possible merit) and that such changes could be inherited (which is false). Thus, by manipulating a seedling's environment, one could channel the "evolution" of crops.

- Appeal was in parallels between biological and political "evolution."

- Lysenko was appealing. He represented the Soviet ideal of the "barefoot scientist", a self-made expert of humble origins and lacking formal education.

- To his credit, Lysenko, by offering revolutionary techniques, managed to motivate Soviet peasants to start farming again in earnest, after the dislocations of civil war and farm collectivization. The problem was with the techniques he advocated.

- His approach didn't epitomize scientific objectivity: "In order to obtain a certain result, You must want to obtain precisely that result; if you want to obtain a certain result, you will obtain it .... I need only such people as will obtain the results I need".

- Lysenko's habit was to report only successes. His results were based on extremely small samples, inaccurate records, and the almost total absence of control groups. He mistrusted the use of mathematics in science. The Soviet press excitedly covered Lysenko's short term success in "vernalizing" the first generation of new kinds of crops but failed to cover subsequent failures of vernalized characteristics to be inherited. (Fear of authorities coupled with the "boring old news" mentality that we have covered previously.)

- 1937: Lysenko became president of the Lenin Academy of Agricultural Sciences.

- 1948: Dissent from Lysenko's theories of environmentally acquired inheritance was made officially illegal. His suppression of his opponents included political denunciations that resulted in some opponents dying in Stalin's Gulag.

- Lysenkoism held official sway in USSR until the mid 1950s, when even the strictest ideologues couldn't help noticing that Lysenko's methods didn't produce the crop yields that he promised. In 1964 it was officially repudiated.

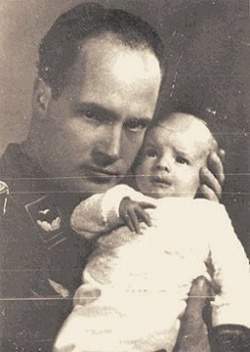

Josef Mengele

- In the SS, he was allowed to continue his anthropological research at the Auschwitz extermination camp.

- Three preoccupations:

- The description/documentation of physical abnormalities

- Alteration of racial features, especially eye color.

- Use of identical twins as controls.

- A handsome spit-and-polish man, capable of appearing benevolent, but pathologically indifferent to human suffering. Many of his subjects were subjected to whimsical but sadistic procedures with no obvious research goal. His subjects were automatically slated for death (although in some cases, their utility as experimantal subjects postponed the fatal moment until they could be rescued.) Of roughly 1500 pairs of twins that he studied, about 100 survived the war.

- Mengele uncomfortably straddles the boundary of real and pseudoscience. On one hand, he had some concept of proper methodology and made real observations, but his ultimate goals (E.G. racial "improvement") were at best in the realm of the purely subjective. Plausible arguments are made that he was merely exercising power for its own sake, as he did when he routinely participated in the selection of incoming inmates, directing the able-bodied to forced labor and the rest to immediate execution.

- Escaped the fall of the Third Reich and died in hiding in South America in 1979.

Methodologically Proper Science Done with Malicious Intent:

Very rare, but when it comes to light it REALLY gives science a bad PR problem.

Sigmund Rascher with justifiably

apprehensive baby

- An opportunistic Luftwaffe Captain and (through his wife) friend of Himmler, transferred to the SS where he held the rank of Untersturmbahnführer (major) Worked a the Dachau forced-labor camp, first testing pharmaceuticals on human subjects, but later gathering data for Luftwaffe on effects of aviation hazards, including hypothermia and decompression. Experiments dealt with:

- High altitude simulations

- Simulations of parachuting into cold North Atlantic waters

- Methods of treating effects of the above:

- protective gear

- heat lamps (which worked but caused serious burns)

- Internal irrigation with hot water (fatal)

- body heat transfer through copulation (this idea was Himmler's personal contribution to the research)

- hot baths (the most successful)

Rascher's lasting achievement was the development of the cyanide "suicide capsule" that could easily be bitten through, a product the eventually served his mentor Himmler well.

Third Reich disclaimer

Think it can't happen here? - The Tuskegee Syphilis Experiment

Protagonists of the Tuskegee Syphilis Experiment

- For forty years between 1932 and 1972, the U.S. Public Health Service (PHS) conducted an experiment on 399 black men (mostly impoverished and poorly educated share-croppers) in the late stages of syphilis. The essence was to gather data on the course of the disease when left untreated. Some specifics:

- Researchers understood from the outset that test subjects would provide most of their useful information in the form of autopsies.

- Subjects were misled into believing that they were receiving medical care when, in fact, they received only placebos.

- Great pains were taken to insure that subjects didn't obtain medical care elsewhere.

The program came to an abrupt halt in 1972 when its existance was made public by the Washington Star. It would be easy to dismiss this as a case of simple racism by a public institution, but that would be misleading also. Consider:

- The project was enthusiastically hosted by the Tuskegee Institute (now Tuskegee University), a historically black college.

- Key researchers and staff on the project were, themselves, black.

So a closer approximation of the truth is that people (black and white) with power and influence decided that a group of society's weakest and least valued members were "expendable."

Blowback: Alas, news of this outrage became widely known and led to a general suspicion of medical research among the general public. For example, researchers must confront the persistant suspicion that HIV was developed in a research lab somewhere. After all,

..that which has happened can, most definitely, happen.

Take home lessons:

- Secrecy stunts scientific inquiry: As we've seen before, official secrecy has bad side effects. In the case of the Tuskegee Experiment, it allowed institutions to get away with something that the majority of Americans would have viewed as a crime, even when it began.

- Scientists never assume the result in advance: Any time scientific research is undertaken with the explicit goal of obtaining a particular result, pseudoscience is the likely outcome.

- Authoritarianism and science don't mix well: Authoritarian governments are inherently hostile to the open skeptical inquiry that science requires, but love the PR charisma of seeming scientific. Thus, both evil science and pseudoscience can be weapons in the arsenals of tyrannical governments. In fact, maybe any government that resorts to their use, or suppresses proper science, is tyrannical by definition.

- The scientific method is morally neutral: Like any other tool, people with their own moral compasses must decide to employ it for good or ill. Just as you can use a wrench either to fit a pipe or to hit an old lady over the head.

- Freedom of information - through which the public knows what questions are being addressed by science, through what methods, and with what results.

- Democracy - through which the public exercises its power to shape the directions and priorities of government supported research.