Morality, abstraction, and concrete reality

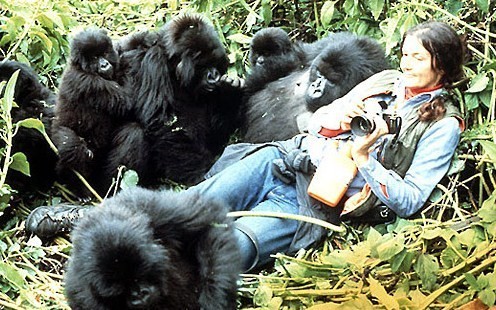

The late Dian Fossey with her best friends

- Orangutans - suffering from logging/habitat destruction Expected for fall below critical thresholds within 50 years.

- Chimpanzees/Gorillas threatened by civil conflict and forest logging that degrades and fragments forests and facilitates ebola transmission.

- Bluebirds, driven out of their nesting sites by invasive exotic Eurasian starlings.

Good enough. We all, to some degree, sympathize with our fellow creatures and very few people would argue that a species is something to be extinguished on a trivial whim. Still as the endangered creatures become less charismatic or unique like the San Francisco garter snake (cf. common garter snake) it is understandable that people would ask if they should stand in the way of new golf courses?

You could argue that such concerns are trivial. Subsistence farmers whose immediate concern is putting food on their table may have no practical opportunity to indulge such concerns. The concrete reality for most people is that concerns for environmental stewardship are something they can't afford. Indeed, how many of you would volunteer to starve to death if you knew it would save the gorillas?

Ultimately people must have:

- Food

- Physical security

- Security from disease

Practically speaking, this means that society must offer the following to 7.8 billion people:

- Agricultural productivity

- Political stability

- Functioning infrastructure

- Energy resources

- Health services

How humanity has done this in the past and might continue in an environmentally uncertain future is the topic of this lecture. For now, we lay aside agriculture, politics, infrastructure, and energy, to focus on general principles.

I - Biological diversity is useful.

Arctic Lemming

- Mass drownings are largely a media-perpetuated urban myth based on the 1958 Disney film White Wilderness. That's not to say that lemmings don't suffer regular mass mortality. During intervals of high population density, lemmings will attempt to migrate to less densely populated regions, usually driven by:

- Starvation, as their reproduction rate allows them quickly to overwhem their resource base within about 4 years.

- Extermination, as predators that specialize in them like stoats, snowy owls, arctic foxes, and long-tailed skuas also experience populations booms.

- Distinction in behavior between lemmings in forest and tundra regions. Forest lemmings are not known for significant boom and crash cycles. Why not?

Boreal forest near McLaren River, AK - Patchiness vs. uniformity: Lemmings in patchy, variable environments like boreal forests can switch from one habitat to another when resources in a particular habitat are exhausted.

Tundra with Denali - Denali National ParkLemmings living a uniform environment like the tundra are just hosed when its resources are exhausted because there is no readily available alternative.

- Of course, when lemming populations crash, so do those of their predators, who may undertake their own mass migrations looking for food. American bird watchers look forward to the occasional eruption of snowy owls into the contiguous US during these events.

The lesson: A diversity of environmental resources is good because it provides you with options when environmental change renders your normal modus operandi untenable.

II - People are rational but plan on a human time scale.

Applications of this principle to human society are diverse, but so are the temptations to ignore them. Consider that:

- People everywhere are basically rational about their self-interest

- but they plan on a time scale of years, not decades

- they can't anticipate novel threats

- they don't like infringements on their autonomy and only submit to them in exchange for material benefits

Tradition!

- Agricultural monocultures

- Reliance on well-established technologies

- Cultural intertia: Self-reinforcing institutional practices, as practitioners educate their successors not only in how to do things, but in why they are worth doing.

III - People don't expect the unexpected and they hang onto institutional practices.

What are the prospects of a human boom-and-crash-cycle? We've seen examples in the past of civilizations that catastrophically fail due to institutions that render their people and environment incapable of supporting them.

Easter Island Moai

- Sophisticated navigational techniques and sea-going vessels based on dugout canoes.

- Agriculture based on taro, yam, breadfruit, chickens, dogs and pigs; supplemented by fishing.

The take home lessons of this and other collapses of civilizations are that:

- The viability of a state absolutely depends on the ability of the environment to support dense concentrations of people

- the ideologies that give civilizations cohesion can become maladaptive under changing environmental circumstances.

The more we limit the diversity of the biological resources on which we depend, the more we set ourselves up for lemming-like boom and crash cycles. The alternative is deliberately to hedge our bets by identifying and exploiting a much wider range of biological resources than we think we need. Natural Biodiversity provides us with a mine of useful products waiting to be domesticated.

Indeed, one food sources that has been left alone because it is economically infeasible now but might become feasible in the future - oak trees. But we leave the discussion of food for later.

The Russet Burbank Potato

Human agriculture and habitat diversity.

- Six varieties of corn -> 46 percent of the crop

- Nine varieties of wheat -> half of the wheat crop

- Two types of peas -> 96 percent of the pea crop.

- More than half the world's potato crop is made up of one variety of potato: the Russet Burbank favored by McDonalds.

- Economies of scale in actual farming

- Economies of scale in manufacture of a small number of types of generic farm machinery

- Maximizes yield allowing cheap food and surplus to export.

- Stimulates demand for products of allied industries

- Pesticides

- Fertilizers

- Machinery

- Antibiotics and other veterinary pharmaceuticals (keeping many animals at close quarters encourages spread of diseases.)

Eutrophication in the Potomac

- Concentration of uniform varieties of crops facilitates evolution of pests specifically adapted to them.

- Separation of farming of animals and plants means that waste that was once routinely recycled as fertilizer is now a large scale waste-disposal problem.

- Environmental risks of industrial farming: Pesticide pollution, eutrophication of waterways from fertilizer runoff.

But all of this is minor compared to the long term threat: As we are well aware, the emergence of novel pathogens like the 1918 Spanish influenza and COVID-19 can cause significant societal damage. At least in the current crisis we can expect the development of vaccines and therapies within a year or so. The day may come when the pests really evolve faster than our ability to cope with them. There have been foreshadowings:

- In 1970 the corn-leaf blight destroyed 60% of US corn production in a single summer.

- Human antibiotic use has facilitated the emergence of rather scary new pathogens, including, in recent years, a highly antibiotic-resistant tuberculosis in southern Africa. Of course, physicians have been training humans to take their full courses of antibiotics for a while. The widespread administration of antibiotics to farm animals (including as prophylaxis) amplifies the danger of the evolution of antibiotic-resistant pathogens that can then jump to humans. It's only a matter of time.

Thus, the human situation - dependance on an agricultural monoculture - mirrors that of the tundra lemmings - dependance on a natural monoculture, just on a longer time scale. Our monoculture is productive now, but the development of agricultural technologies must be in a constant race with:

- The evolution of pathogens

- The accumulation of environmental problems

The worst-case scenario is a full-blown human boom and crash cycle. We have discussed smaller scale versions of these, but there is something distancing about the fact the our example, Easter Island, was a remote pre-industrial societies. Consider an industrial-age example:

At first:

- Prior to the potato, roughly 1/3 of Ireland was too boggy or rocky to be arable by conventional means.

- Ireland's economy was dominated by absentee landlords who rented parcels to tenant farmers. Laws favoring landlords discouraged actual residents from making improvements to property.

And then:

- Changed with introduction of potato in 1590 - a low-maintainance crop that grew in otherwise waste regions. Indeed, the potato was more nutritious than alternative crops, and by 1800 Ireland was a potato monoculture for purely rational reasons.

- Between 1845 and 1851 the potato crop was largely destroyed by a fungal blight recently imported from the New World (Phytophthora infestans). During that interval Ireland's population dropped by roughly 20% (12% starved, 8% emmigrated) as food production failed and the economic system collapsed. (By British policy, food relief was to be funded by taxes on landlords who became bankrupt as they could no longer collect rent from starving tenants.)

As bad as it was, the famine was mitigated by:

- Eventual aid from the British Crown and other nations.

- Proximity to places of refuge (England and North America)

- The fact that the blight was local.

Just a similar blight today affecting rice in mainland Asia.

Heirloom corn varieties

- People were doing what they were culturally accustomed to doing.

- But they did it in new geographic circumstances or with new materials

- And lacked institutions to coordinate responses to unusual threats

IV - Pharmaceuticals are like crops.

Pacific yew - Taxus brevifolia

- Anticarcinogen Paclitaxel from pacific yew trees (right) became available in 1996. Used against breast and ovarian cancers, some lung cancers, and leukemia.

- EC3 An anticlotting drugbased on the venom of the saw-scaled viper, Echis carinatus, that is shortly to become available;

- Compounds derived from the venom of cone snails form the basis of a new generation of powerful analgesics;

- An alkaloid secreted in the skin of the frog Epipendobates tricolor that is in early clinical trials as another analgesic.

- A Exenatide compound identified in Gila monster saliva (that's right) mitigates the effects of diabetes.

National Council on Biodiversity and Human Health proposed by pharmacological industry in 1998.

V - The hypothesis that biological diversity is useful is testable.

I began with the fates of lemmings in natural environments of variable diversity as a metaphor for the prospects of human society in unnatural agricultural environments, then gave anecdotes about human survivability. Can we put any of this on a quantitative footing?

Yes, we can.

Biological productivity as a function of diversity:

- Mathematical models: In recent years, mathematical ecosystem models have become more sophisticated. Models of Loreau et. al. (2001) indicated that although stable environments at equilibrium may be most productive when dominated by a small number of species, the situation changed radically when environments were variable. In such cases, habitats with greater diversity were better able to cope with change without reducing productivity. This was true even though there was some element of chance regarding which species would ultimately become dominant.

- Empirical studies: Vindicate mathematical results, with experiments (E.g.: Tilman et al., 2001) showing greater productivity of diverse plots than of monocultures.

VI - Ecosystems Services: Because it's free doesn't mean it's worthless.

Ecosystem Services:

"The flow of materials, energy, and information from natural capital stocks which combine with manufactured capital and human capital to produce human welfare." Costanza et al. 1997

But that is so academic. Society is driven by markets and individuals have no option but to make practical choices. Moreover, we regard it as axiomatic that:

- A society's living standard can be approximated by its GDP - the total cost of goods and services sold in its economy.

- A thing's value, by definition, is what people are willing to pay for it.

The problem is that most ecosystem services - services rendered to humans by a healthy environment that researchers may easily be able to quantify- are not directly part of the money economy and market system. We can measure the air you breathe, for instance, but economists would be puzzled by the idea of monetizing it.

Bumblebee - tireless pollinator

- Provisioning Services - products obtained from ecosystems.

- Food (wild game, including seafood)

- Water

- Pharmaceuticals

- Minerals

- Energy

- Pollination

- timber

- Supporting Services - services necessary to create more services.

- Nutrient dispersal

- Seed dispersal

- Soil formation

- Biodiversity

- Habitat

- Immune system maintenance

- Regulating Services - services from the regulation (homeostasis) of ecosystems processes.

- Waste decomposition

- Water purification

- Carbon sequestration

- Flood control

- Clean air

- Cultural Services - services from the enjoyment ecosystems processes.

- Recreation

- Aesthetic

- Stewardship

- Education

So, you pay nothing for air, an ecosystem service outside of the money economy. That doesn't mean we can't put a money value on your air.....

What would you be willing to pay for a substitute for air if something took your air away?

We can ask that question about any benefit we receive from the environment. Estimating the replacement cost of "ecosytem services," - environmental benefits that are outside of the money system but whose replacement would cost money is a current priority of environmental economists. A seminal review by UMD researcher Robert Costanza et. al. summarized published data for a broad range of ecosystem services and suggests:

- Estimates of the value of major ecosystem services range from $16-54 trillion per annum. Note, global GDP is around $18 trillion per annum. Thus, a low-ball estimate is that the value of the environment to us is equal to our total GDP - i.e it would cost at least that much to replace.

- How much money are we already spending to replace environmental benefits that we once got for free? If we subtract estimates of this replacement cost from the official GPD of the money economy, we can estimate the true growth of our affluence. By this standard, it appears that our true affluence has leveled off. By some estimates it peaked during the 1970s.

Kaaterskills Falls, NY

- Construction of adequate water treatment facilities: $7-8 billion

- Land use changes to remediate runoff at the source: $600 million.

How could we have missed something this big? In large part because traditional economics evaluates the productivity of an environment by the value of major products that it produces. Thus, when the landowners of a tropical island abounding in biological diversity and surrounded by reefs make their money from logging, the land's productivity would be measured in units of trees cut down.

The Costanza et al. study has stimulated the rise of ecosystem service economics and related fields, as researchers have attempted to:

- Place values on threatened ecosystem services in specific regions:

- Develop methodologies for the economic study of ecosytem services:

- Indeed, UN Secretary General Kofi Annan formed an investigatory group analogous to the IPCC - the Millenium Ecosystem Assessment - in response to Costanza et al.:

- Guide to MEA reports

- Living Beyond our Means, the primary report.

The long term goal is the development of True Cost Accounting that encompasses the value of ecosystem services. This requires overcoming both traditional accounting practices and...

Not everyone can have another cow.

The Tragedy of the Commons

Remember, humans are rational but self-interested. What happens when a resources is held in common? Everyone has an incentive to overexploit it. The classic example is the collective overgrazing of communally held pastures in traditional villages.

In all of the foregoing, we see that environmental change poses threats to the biodiversity on which we rely and challenges our ability to cope with changing ecosystems. What does the deep history of biodiversity actually tell us about global change? That is for next week.

Whatever the details, our practical decisions about biodiversity biodiversity need to be informed by:

- Recognition of its importance as a source of ecosystem services.

- Recognition that we don't think about the value of many such services because they are outside the money economy.

- Recognition that tried and true institutional practices can fail when conditions change.