Eugnathostomata, Chondrichthyes, and "spiny sharks"

All contemporary analyses agree that the living gnathostomes:

- Chondrichthyes: the cartilaginous fish

- Osteichthyes: the bony fish

From the SUNY Orange

- The myomeres of lampreys (right) and hagfish are continuous from top to bottom. Those of living gnathostomes are divided into dorsal and ventral blocks by a horizontal septum of connective tissue. (See transverse cross-section). Trinajstic et al., 2007 describing fossils with exceptional soft tissue preservation show that arthrodires and ptychtodontids, like lampreys, lacked the horizontal septum.

Alternative palatoquadrate articulations with neurocranium

(Few have all of these.) - Palatoquadrate articulates with neurocranium dorsally. (In placoderm-grade gnathostomes it was attached to the medial surface of the dermal bones of the skull roof.)

- Primary jaw adductor muscle mass is lateral to the mandibular arch. (Among placoderm-grade gnathostomes, the palatoquadrate is attached to the dermal skull roof, and the jaw muscles pass medially to it.)

Lower dentition of Heterodontus - Teeth: Odontodes of the oral cavity anchored either in soft tissue around palatoquadrate and Meckel's cartilage, or in dermal bone at margin of mouth. We have seen their putative precursors in Thelodonti and placoderm-grade gnathostomes. In Eugnathostomata we finally see oral odontodes that all researchers are comfortable in regarding as homologous. Their features:

- Subject to regular replacement, causing them either to be shed or to accumulate in whorls.

- Bearing outer layer of enamel (interlocking apatite crystals without organic matrix). Note, tooth formation requires inductive interaction of mesodermal odontoblasts to produce dentin and pulp cavity and ectodermal ameloblasts to produce enamel.

Dorsal view of Placoderm (left) and eugnathostome (right) braincases after Schultze, 1993. - Loss of anterior neurocranial fissure (between ethmoid region and remainder of neurocranium)

Lateral view of Placoderm (above) and eugnathostome (below) braincases after Schultze, 1993. - Incomplete fusion of the occipital arch and otic region results in a lateral otic fissure through which cranial nerve X passes. (Equals metotic fissure of some authors.)

Ventral view of Placoderm (left) and eugnathostome (right) braincases after Schultze, 1993. - Elongation of the sphenoid region with respect to the otico-occipital region. In placoderms, the otico-occipital region can take up up to 3/4 the length of the neurocranium. In Eugnathostomes, this is reduced.

Mimipiscis neurocranium - Ventral cranial fissure in floor of braincase between otic (parachordal) and sphenoid (trabecular) regions. (Note: This feature is usually associated with Osteichthyes, but has recently been observed in the stem chondrichthyan Pucapampella (Maisey and Anderson, 2001).)

- Amphistylic suspension of palatoquadrate: Palatoquadrate articulates with neurocranium both directly and via hyomandibula.

Eugnathostome diversity:

Osteichthyes: Wedgetail triggerfish Rhinecanthus rectangulus (right); Chondrichthyes: Blue-spotted lagoon ray Taeniura lymna (left)

Two major living groups:

- Chondrichthyes (Silurian - Quaternary) - Living cartilaginous fish and their fossil relatives

- Osteichthyes (Silurian - Quaternary) - living bony fish and their fossil relatives

Chondrichthyes

Living chondrichthyan diversity include:

- Chimaeriformes: (Carboniferous - Quaternary) Chimaeras and fossil relatives

- Neoselachii: (Triassic - Quaternary) Shark-like chondrichthyans.

Dorsal view of Xenacanthus sp. braincase

after Schultze, 1993.

- Prismatic perichondral calcification of the cartilage: It is often said that chondrichthyans lack internal bone. While true, it is not quite diagnostic. Unlike bone, prismatic calcification takes the form of chains of tiny apatite crystals covering the surface of cartilage, linked together by collagen. Note: Chondrichthyans do not lack other hard tissues. Various groups make teeth, fin spines, and dermal armor out of dentine and enamel. Finally, bone is present as a component of scales.

- Precerebral fontanelle: A trough-like dorsal opening in the ethmoid region medial to the nasal capsules (right).

- Lateral otic process of the otic region (right).

- Eugnathostome ventral cranial fissure and lateral otic fissure are secondarily closed.

- Teeth develop as whorls anchored directly in palatoquadrate or Meckel's cartilage with new teeth being added medially, migrating to a functional position, then being shed laterally. (Dearden and Giles, 2021)

- Claspers on pelvic fins as intromittant organs.

Chondrichthyan diversity

Stem chondrichthyans: The earliest unambiguous chondrichthyan remains are from the Early Silurian, but consist of isolated scales. (Possible chondrichthyan scales extend into the Late Ordovician.) We pick up relatively complete fossil chondrichthyans during the Devonian, however their first great radiation occurred during the Early Carboniferous. Alas, there is much disagreement about the phylogeny of basal chondrichthyans. Our review is based on Coates et al., 2017. The cladogram at right provides a consensus of recent hypotheses. Euchondrichthyes (Pradel et al., 2011) is the last common ancestor of living chondrichthyans and all of its descendants. We consider the living groups first, then try to make sense of the stem taxa.

Elasmobranchii:

(Devonian - Quaternary) Chondrichthyans closer to living sharks than to living chimaeras. The cladogram (right) presents a general consensus of elasmobranch phylogeny.Synapomorphies:

- Vertebral column in which arcualia form distinct neural arches that are inserted into the notochord.

- Hypobranchial elements of branchial arches point posteriorly. (Contrast with osteichthyan pattern.)

- Cladodont teeth ancestrally - One tall central cusp is flanked by smaller cusplets.

- Pectoral fin skeleton formed around:

- three basals (cartilage)

- numerous radials (cartilage)

- ceratotrichia (keratin)

Elasmobranch diversity:

Xenacanthida: (Carboniferous (or Devonian?) - Triassic)Predators with elongate bodies. During the Carboniferous and Permian, they were among the top marine predators. After the end Permian extinction, stragglers held on in fresh water.

Synapomorphies:

- Dorsal fins confluent, with second fins spine lost

- The anterior dorsal fin spine is dissociated from the dorsal fin.

- Tail is, effectively diphycercal. The lower lobe appears as a second anal fin.

- Teeth are cladodont but forked, with the medial cusp reduced.

- Pectoral fin:

- Basals develop into an elongate metapterygial axis

- Radials on medial and lateral sides of metapterygial axis

Noteworthy plesiomorphy:

- The lateral otic fissure of the neurocranium persists. (In other elasmobranchs, it is closed.)

- Palatoquadrate suspension remains amphistylic.

Ctenanthidae: (Devonian - Triassic)

Synapomorphies:

- Fin spines with distinct characteristic ornamentation.

- The anterior dorsal spine slopes strongly posteriorly.

Hybodontiformes: (Carboniferous - Cretaceous) Hybodonts radiated during the late Paleozoic, along with other elasmobranchs, suffered in the end Permian extinction, but rebounded to become the primary elasmobranchs of the Triassic and Jurassic. From the late Jurassic, their diversity diminished. For most of the Cretaceous, they were restricted to fresh water. Coates 2013 argues that the Carboniferous form Tristychius (right) possessed an ecology similar to that of a living nurse-shark.

Synapomorphies:

- Characteristic fin spines.

- Hooked denticles on face.

White-tipped reef shark Triaenodon obesus

Synapomorphies:

- Placoid scales with:

- an outer layer of dense, enamel-like vitrodentin

- an basal collar of bone.

- Three distinct layers of tooth enamel.

- Hyostylic palatoquadrate suspension. Only a flexible ethmoid articulation remains. Enables protrusion of jaws to facilitate bite.

- Ethmoid region of braincase elongated into a rostrum that protrudes above mouth.

- Notochord calcifies into centra that correspond to neural arches. (Link to model)

- Pectoral and pelvic girdle elements articulate at midline.

Batomorphi: (Jurassic - Quaternary) Includes the strong specializations for bottom-dwelling, including:

- Myliobatiformes - Stingrays, eagle-rays, mantas.

- Rayiiformes - Skates.

- Torpediniformes - Electric rays

- Rhinopristiformes - sawfish, guitarfish, etc.. With less exaggerated pectoral fins, but elongate rostra.

Synapomorphies:

- Ventrolateral and anterolateral cartilages of the nasal capsule support anterior head or articulate to the skeleton of the pectoral fin.

- Palatoquadrate articulation with neurocranium is utterly hyostylic, with no suggestion of a direct articulation with the braincase, and extremely mobile.

- The hyoid arch is simplified by the loss of ceratohyals and basihyals.

- Spiracles are greatly enlarged and are important in breathing.

- The last basibranchial articulates with the scapulocoracoid, functionally linking breathing and swimming.

- Anterior arcualia and centra fused into synarcual.

- Basal cartilages of pectoral fin articulate separately with scapulocoracoid.

- Loss of anal fin

The ecology of Batomorphi is generally uniform, with members being dorsoventrally flattened with enlarged pectoral fins for stabilizing bodies on the bottom and specializing in capture of hard-shelled prey. Some myliobatiforms, however, have left the bottom, using their pectoral fins for subaqueous flight. Eagle rays, cow-nosed rays, mobula rays and mantas, for example. What do they do there? They are adapted to suspension feeding.

In this, they parallel the Late Cretaceous "eagle shark" Aquilolamna millrace, a suspension-feeding lamnid galeomorph with elongate pectoral fins.

Squalea: (Triassic - Quaternary) Includes the sharks with an evolutionary tendency to specialize in cold and/or bottom waters, including:

- Squalomorpha - Relatively unspecialized five-gilled cold-water sharks like Squalus acanthias (right).

- Hexanchiformes - Deep ocean specialists with six or even seven branchial arches. (E.G. Notorhynchus cepedianus)

- Squatiniformes - angelsharks. Flattened bottom-dwellers convergent on Batomorphi with large pectoral fins, convergent on skates and rays.

- Pristophoriformes - sawsharks. A second bottom specialist group but with a long rostrum, convergent on sawfish.

Shortfin Mako Shark Isurus oxyrinchus by Callaghan Fritz-Cope

from Pelagic Shark Research Foundation

Galeomorpha also includes the large living suspension-feeding whale sharks and basking sharks, and the Cretaceous manta-ray mimic Aquilolamna milarcae (Vullo et al., 2021).

Synapomorphies:

- Expanded pharyngeobranchials

- Coracoids fully fused on midline

- Spiracle reduced or absent

Neoselachian phylogeny: Two historical hyupotheses.

- Hypnosqualea Hypothesis - Specialized bottom dwelling "flat sharks" and their derivatives constitute a derived clade within Squalea. (Shirai, 1992.) Supported by morphological characters. Reservations include the Hypnosqualea clade's being less strongly supported than Gaeomorpha or Batomorphi. Also, stratigraphic incongruity results from Batomorphi appearing in Early Jurassic whereas Squatiniformes and Pristoriformes don't appear until early Cretaceous, despite being more basal in hypnosqualean trees.

- Batomorphi Hypothesis - "Flat sharks" are polyphyletic, with Batomorphi being the sister taxon to all other neoselachians and Squatiniformes and Pristorophiformes being derived taxa within Squalea. (Kousteni et al., 2021.) Strongly favored by molecular phylogenies and resolves stratigraphic incongruence, but invokes odd sequences of character acquisition.

Hot potato: Protospinax annectens (Solnhofen - Late Jurassic), known from several relatively completespecimens. Displays the bare beginning of tendency toward enlarged pectoral fins and flattened body as if it were a stem batomorph. In fact, the phylogenetic analysis accompanying its recent redescription by Jambura et al., 2023 provisionally associates it with the other flat-sharks as sister taxon of the Squatiniformes-Pristorophiformes clade within Squalea, although the authors, themselves, note the weakness of the support.

However Protospinax shared its world with derived batomorphs like Asterodermus. It is well-placed stratigraphically to display the ancestral state of the Squatiniformes-Pristorophiformes clade.

Euchondrocephali:

Euchondrocephali: (Devonian - Quaternary) Total group including living Chimaeriformes and all taxa closer to them than to Elasmobranchii. Living members, the Chimaeriformes, are clearly distinct from Elasmobranchii, but as one goes back in time, the two groups become harder to distinguish.Synapomorphies are technically complex except for one:

- Enlarged orbits

Euchondrocephali diversity:

Cladoselachida: (Devonian) Including Cladoselache, the earliest well-known chondrichthyan, and similar forms. Maghriboselache (mid-Faminian) and Cladoselache (Late-Famenian) are known from numerous well preserved skeletons. Up to a meter in adult length. Superficially shark like, anatomically suited as fast pursuit predator with tall tail, narrow trunk, and caudal peduncle finlets to reduce drag of tail base. Stomach contents can include fish swallowed tail first, euconodonts, and invertebrates. Interesting features include:

- Reduction of the pelvic fins and absence of anal fins.

- Absolutely absence of claspers, including from specimens inferred on other grounds to be male. A secondary loss?

- In Maghriboselache, specimens are dimorphic for presence of anterior dorsal fin. In presumed males, these are present with a robust spine. In presumed females, absent. (Klug et al., 2023.)

- For the record, Maghriboselache's nasal capsules are spaced far apart, making it the first known example of the hammer-head ecomorph.

Denaea from Carroll, 1988.

The earliest known is the mid-Famenian Ferromirum. It preserves features including a hyostylic palatoquadrate suspension reminiscent of later galeomorphs, enabling it to maximize exposure of its teeth to prey, making it a fierce but tiny (33 cm) predator. (Frey et al., 2020)

Synapomorphies of Symmoriida:

- Pectoral fin with extremely long metapterygial axis posterior to basal cartilages

- Anal fin lost

- Anterior dorsal fin lost or, in males, developed as bizarre display structures, a further development of the dimorphism noted in Maghriboselache. Despite this similarity,

- Unperforated chondrocranium roof in optic-occipital region

- Confinement of occipital arch to the region between otic capsules

Additionally, symmoriids give a glimpse of the evolution more derived features that characterize living euchondrichthyans:

- The chimaeriform operculum: Elasmobranchii uniformly possess naked branchial openings with no suggestion of an operculum, whereas living Chimaeriformes have a full operculum supported by cartilaginous extensions fringing the hyoid arch. The Carboniferous symmoriid Cosmoselachus mehling seems to have possessed a rudimentary operculum covering at least the first two branchial openings. (Bronson et al., 2024.)

- The elasmobranch branchial arches:

Ozarcus mapesae (Carboniferous) A basal euchondrocephalian according to Coates et al., 2017. A small symmoriid Pradel et al. 2014

described from CT scans. Although the braincase and amphistylic jaw suspension are typically chondrichthyan, the branchial arches are not:

- The pharyngeobranchials slope anteriorly in the manner of Osteichthyes.

- Accessory elements like those seen in Osteichthyes are present

Eugeneodontida: (Carboniferous - Triassic) Shark-like predators with interesting teeth. Although many chondrichthyans retain their teeth in whorls rather than shedding them, eugeneodontids tend to have exaggerated symphyseal tooth whorls in the lower jaw that fit into corresponding whorls in the upper. Tapanila et al., 2013 have redescribed Helicoprion, long known from its tooth whorl, based on CT scans, revealing it to be a basal euchondrocephalian. Clears up a century of competing interpretations. (Link to image by Ray Troll.) Additionally:

- Often with long rostrum, E.G. Ornithoprion.

- One dorsal fin lost (but which?)

- Anal fin lost

- Pelvic fins lost. (Or so it appears. Strange. Did they use claspers?)

Debeerius ellefseni: (Carboniferous) An exceptionally well-preserved fossil.

- The familiar broad otic process of the palatoquadrate is lost

- the hyoid arch is not involved.

Holocephali:

(Devonian - Recent) Living Chimaeriformes and their closest relatives: Many develop dermal skull plates made of dentine. Generally speaking, holocephalians are slow moving and specialize on crushing hard-shelled organisms.

Synapomorphies:

- Holostylic palatoquadrate suspension, a derived "special case" of autodiastylic condition, in which the palatoquadrate actually fuses with the neurocranium.)

- Teeth specialized for crushing - often fusing into broad tooth plates.

- The anterior arcualia fuse into a synarcual.

- Spine of the first dorsal fin articulates with the synarcual

- Second dorsal fin has no spine.

A rogue' gallery of Holocephali:

Iniopterygiiformes: (Carboniferous) Proportionally similar to chimaeras except:

- just as some rays taken to subaqueous flight using their pectoral fins, these seem to have done the same.

- Their pectoral fins attach far up on the body wall.

- They frequently have extensive bony plates on their skulls.

- Although Chimaeriformes (the living Holocephali) are specialized for crushing hard-shelled prey, at least one iniopterygian, Iniopera, has been modeled as using suction-feeding. (Dearden et al., 2023.)

Cochliodontidae: (Devonian - Permian) Small holocephalians with holostylic jaw suspension. E.G. Helodus simplex (right). Distinguished by:

- Distinctive tooth plate pattern.

- Frequent presence of paired "bottle brush" spines on head

Menaspidae: (Devonian - Permian) Small holocephalians with holostylic jaw suspension. Distinguished by:

- Four pairs of head spines (derived from labial cartilages?)

- Bony dermal plates of head comprised of cyclomorial scales.

Petalodontiformes: (Carboniferous - Permian) Distinguished by:

- Petal-shaped teeth

- Broad pectoral fins similar to those of skates coupled with a laterally compressed body.

Chimaeriformes: The Euchondrocephalian Crown

(Carboniferous - Recent) Noteworthy characteristics of Chimaeriformes - the living group:

- Odd cartilages of face perform numerous functions.

- Branchial arches tucked beneath braincase and covered by a single gill cover.

- Hyoid arch has a pharyngeohyal dorsal to the hyomandibula (analogous to pharyngeobranchials of branchial arches.)

- Hyoid arch supports the gill cover and has no association with the palatoquadrate.

Stem chondrichthyans:

As we survey farther down the chondrichthyan tree, we find creatures that share chondrichthyan synapomorphies but increasingly share ancestral characters with other gnathostome groups. A sampling:Doliodus problematicus (Early Devonian) Roughly 1 m long, it shows classic chondrichthyan synapomorphies. Interesting because its pectoral fins have spines of dentin like those of the dorsal fins. We will meet this feature again.

Pucapampella (Early Devonian) Known from two braincases, according to Maisey and Anderson, 2001, this animal clearly preserves a ventral cranial fissure, otherwise known only from osteichthyans.

A general pattern emerges in which, the farther down the chondrichthyan branch we push:

- The less clearly distinct animals become from osteichthyans

- The more placoderm-grade plesiomorphic features we recognize.

Acanthodii

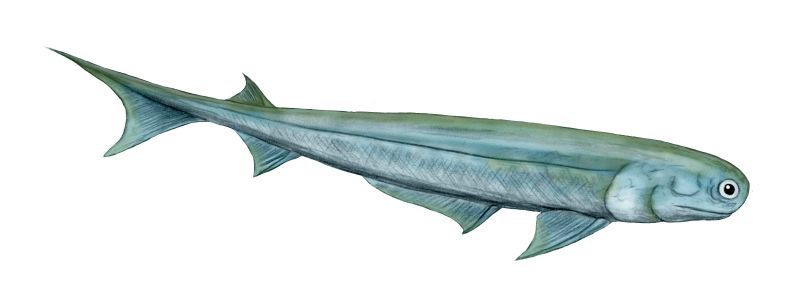

(Late Ordovician - Permian)A final gnathostome group demands attention: Acanthodii (aka "spiny sharks.") Small animals (10 - 30 cm) characterized by:

- Fin spines on all fins. (In some, intermediate fin spines develop from the ancestral postbranchial fin-fold. Also, cf. Doliodus, above.)

- Characteristic small rhomboidal scales that grow by circumferential accretion to a primordium.

- Often lack teeth or, when they are present, lack evidence for regular replacement. Dearden and Giles, 2021 note that teeth in many acanthodians are fused to a dermal "dentigerous bone" lining Meckel's cartilage or palatoquadrate, and suggest that teeth evolved more than once among them.

- Anal fin supported by a spine (unique)

Climatius from Carroll, 1988

- Very heavy fin spines.

- Four pairs of intermediate spines between pectoral and pelvic fins.

- Multiple external gill slits, partially covered by a larger operculum. (Armored by branchiostegal rays.)

- anterior and posterior dorsal fin.

Acanthodes: (Permian)

- very light fin spines

- one pair of intermediate spines

- Gills entirely covered by operculum.

- Anterior dorsal fin lost.

- Overall resembling a spiny version of the basal osteichthyan Cheirolepis

Difficulty: Generally speaking, one would expect that in an evolving monophyletic group, the more derived taxa would occur later in time than the more ancestral ones. This is called stratigraphic congruence. Acanthodians display the opposite pattern. The most freakishly spiny ones are also early.

Acanthodes neurocranium mandibular, and hyoid arches

- Placoderms are paraphyletic

- Acanthodians are paraphyletic, with:

- some (like Climatius) basal to Eugnathostomata

- some (like Acanthodes) closer to Osteichthyes

- some (like Kathemacanthus) closer to Chondrichthyes

- a body covered with a mosaic of small scales but no dermal bone plates

- a cartilagenous endoskeleton

Everyone was happy that the enigma had been resolved. But only until 2013.

The Source of All Disquiet

Then came Zhu et al. 2013, reporting on Entelognathus primordialis, a placoderm-like creature with extensive bony cranial and thoracic armor and:

- Osteichthyan - like dermal cranial elements: the premaxilla, dentary, and maxilla.

- Jaw adductor musculature on both the medial and lateral sides of the palatoquadrate.

Adding color to this pattern:

- Sahney and Wilson, 2001 discovered the described the remains of open endolymphatic ducts in the acanthodians Brochoadmones, Ischnacanthus, Lupopsyrus, and Tetanopsyrus - a feature shared with living chondrichthyans but not osteichthyans.

- Davis et al. 2012 redescribed the skull of Acanthodes - the most osteichthyan-like of acanthodians - and found it to be more chondrichthyan-like than previous describers had.

- Brazeau and de Winter, 2015 examine the skull of Acanthodes, revealing that it's hyomandibula articulates with the braincase ventrally to the jugular vein, as in chondrichthyans. In osteichthyes, this articulation either straddles the vein or is dorsal to it. We don't know which state is derived, but the similarity to living chondrichthyes is striking.

- Gladbachus adentatus (Middle Devonian) Coates et al., 2018 describe the results of his CT scans of Gladbachus, an 80 cm, chondrichthyan without fin spines, noting:

- The shape of the neurocranium is reminiscent of that of placoderm-grade gnathostomes

- The hyoid arch, although involved in jaw suspension, is not strongly differentiated from adjacent branchial arches

- The shape of the palatoquadrate suggests that at least some of the adductor muscle mass passed medially to it, as in placoderms.

- In their phylogenetic analysis, Gladbachus is nested among acanthodian-grade chondrichthyans - a spineless spiny shark!

So we now accept this pattern:

Euchondrichthyan Evolutionary Patterns

First chondrichthyans: Individual scales resembling those of chondrichthyans are known from the Late Ordovician, however the first reliable fossil chondrichthyan is Shenacanthus vermiform: from the Early Silurian. It co-occured with the oldest known placoderm, Xiushanosteus mirabilis. Phylogenetic position unclear, but plesiomorphically retaining extensive thoracic armor - a chondrichthyan that remembers its placoderm roots! Like Xiushanosteus, Shenacanthus is tiny, the size of a black molly. (Zhu et al.)Paleozoic diversity patterns: Although inferred to be present by the Early Silurian, gnathostome diversity only starts to climb in the Devonian, led by placoderm-grade vertebrates but accompanied by chondrichthyes and osteichthyes. Adjusting for sampling and preservation biases, Schnetz et al., 2024 identify two major pulses of chondrichthyan diversification:

- Stem chondrichthyans (mostly acanthodians) diversify in the Early Devonian, but their diversity diminishes in the Late Devonian and trails off subsequently. By the Carboniferous, they are a "dead grade swimming." (Schnetz et al.)

- Euchondrichthyes, mostly represented by Euchondrocephali, diversifies in the Late Devonian, reaching a diversity peak in the Carboniferous. Elasmobranchii, while consistently present, are a minor component of this radiation. Arguably, this radiation is coordinated with The Devonian Nekton Revolution and accelerates as euchondrocephalians radiate into durophagous niches evacuated by the end Devonian Hangenberg extinction event. The rise of durophagous euchondrocephalians and the "crinoid garden" environments of the Early carboniferous seem suspiciously coordinated.

Euchondrichthyan diversity crashes in the Early Permian and does not recover until the Mesozoic, when Elasmobranchii take the lead. (Schnetz et al.)

Additional reading:- Martin Brazeau, (2009) The braincase and jaws of a Devonian "acanthodian" and modern gnathostome origins. Nature 457, 305-308.

- Martin Brazeau and Valerie de Winter, (2015) The hyoid arch and braincase anatomy of Acanthodes support chondrichthyan affinity of 'acanthodians.' Proceedings of the Royal Society B 282: 20152210. http://dx.doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2015.2210.

- Allison W. Bronson, Alan Pradel, John S. S. Denton, John G. Maisey, 2024. A new operculate symmoriiform chondrichthyan from the Late Mississippian Fayetteville Shale (Arkansas, United States) Geodiversitas 2024, 46(4).

- Coates, Michael (2013) Sharks and the deep origin of modern jawed vertebrates The Palaeontological Association 57th Annual Meeting Podcast.

- Michael I. Coates, Robert W. Gess, John A. Finarelli, Katharine E. Criswell, and Kristen Tietjen. 2017. A symmoriiform chondrichthyan braincase and the origin of chimaeroid fishes Nature 541, 208–211.

- Michael I. Coates, John A. Finarelli, Ivan J. Sansom, Plamen S. Andreev, Katharine E. Criswell, Kristen Tietjen, Mark L. Rivers, and Patrick J. La Riviere (2018) An early chondrichthyan and the evolutionary assembly of a shark body plan. Proceedings of the Royal Society B 285(1870).

- Davis, Samuel P., John A. Finarelli, Michael I. Coates (2012) Acanthodes and shark-like conditions in the last common ancestor of modern gnathostomes. Nature 486, 247-250.

- Richard P. Dearden and Sam Giles, (2021) Diverse stem-chondrichthyan oral structures and evidence for an independently acquired acanthodid dentition. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 21(4), 702 - 713.

- Richard P. Dearden, Anthony Herrel, and Alan Pradel, (2023) Evidence for high-performance suction feeding in the Pennsylvanian stem-group holocephalan Iniopera. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 120 (4) e2207854119.

- de Carvalho, M.R. 1996. Higher-Level Elasmobranch Phylogeny, Basal Squaleans and Paraphyly. In Interrelationships of fishes; Stiassny, M.L.J., Parenti, L.R., Johnson, D.G., Eds.; Academic Press: London, UK; New York, NY, USA; San Diego, CA, USA, 1996; pp. 35–62.

- Linda Frey, Michael I. Coates, Kirsten Tietjen, Martin Rücklin, Christian Klug. 2020. A symmoriiform from the Late Devonian of Morocco demonstrates a derived jaw function in ancient chondrichthyans. Communications Biology 3 - 681.

- Guillaume Guinot and Fabien L. Condamine. 2024. Global impact and selectivity of the Cretaceous-Paleogene mass extinction among sharks, skates, and rays. Science 379(6634), 802-806.

- Patrick L. Jambura, Eduardo Villalobos-Segura, Julia Türtscher, Arnaud Begat, Manuel Andreas Staggl, Sebastian Stumpf, Renó Kindlimann, Stefanie Klug, Frederic Lacombat, Burkhard Pohl, John G. Maisey, Gavin J. P. Naylor, and Jügen Kriwet. 2023. Systematics and Phylogenetic Interrelationships of the Enigmatic Late Jurassic Shark Protospinax annectans Woodward, 1918 with Comments on the Shark–Ray Sister Group Relationship. Diversity 15(5)

- Christian Klug, Michael Coates, Linda Frey, Merle Greif, Melina Jobbins, Alexander Pohle, Abdelouahed Lagnaoui, Wahiba Bel Haouz, and Michal Ginter. 2022. CBroad snouted cladoselachian with sensory specialization at the base of modern chondrichthyans. Swiss Journal of Paleontology 142(2).

- Kousteni, V.; Mazzoleni, S.; Vasileiadou, K.; Rovatsos, M. 2021. Complete Mitochondrial DNA Genome of Nine Species of Sharks and Rays and Their Phylogenetic Placement among Modern Elasmobranchs. Genes 2021, 12, 324.

- John Maisey and M. Eric Anderson, (2001) A primitive chondrichthyan braincase from the Early Devonian of South Africa. Royal Society Open Science 8: 210822. https://doi.org/10.1098/rsos.210822.

- Alan Pradel, Tafforeau P, Maisey JG, Janvier P (2011) A New Paleozoic Symmoriiformes (Chondrichthyes) from the Late Carboniferous of Kansas (USA) and Cladistic Analysis of Early Chondrichthyans. PLoS ONE 6(9): e24938. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0024938.

- Alan Pradel, John G. Maisey, Paul Tafforeau, Royal Mapes and Jon Mallatt (2014) A New Paleozoic A Palaeozoic shark with osteichthyan-like branchial arches. Nature 509, 608-611.

- Sarda Sahney and Mark Wilson, (2001) Extrinsic labyrinth infillings imply open endolympahtic ducts in Lower Devonian osteostracans, acanthodians, and putative chondrichthyans. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 21(4), 660 - 669.

- Lisa Schnetz, Emma M. Dunne, Iris Feichtinger, Richard J. Butler, Michael I. Coates, and Ivan J. Sansom. (2024) Rise and diversification of chondrichthyans in the Paleozoic. Paleobiology. 2024;50(2):271-284. doi:10.1017/pab.2024.1.

- Shirai, S. Phylogenetic Relationships of the Angel Sharks, with Comments on Elasmobranch Phylogeny (Chondrichthyes, Squatinidae). Copeia 1992, 1992, 505–518.

- Leif Tapanila, Jesse Pruitt, Alan Pradel, Cheryl Wilga, Jason Ramsay, Robert Schlader, Dominique Didier. 2013. Jaws for a spiral-tooth whorl: CT images reveal novel adaptation and phylogeny in fossil Helicoprion. Biology Letters 9, 20130057. http://dx.doi.org/10.1098/rsbl.2013.0057.

- Kate Trinajstic, Carina Marshall, John Long, Kat Bifield. 2007. Exceptional preservation of nerve and muscle tissues in Late Devonian placoderm fish and their evolutionary implications. Biology Letters 3(2).

- Villalobos-Segura, E.; Marrama, G.; Carnevale, G.; Claeson, K.M.; Underwood, C.J.; Naylor, G.J.P.; Kriwet, J. The Phylogeny of Rays and Skates (Chondrichthyes: Elasmobranchii) Based on Morphological Characters Revisited. Diversity 2022, 14, 456.

- Romain Vullo, Eberhard Frey, Christina Ifrim, Margarito A. Gonzalez Gonzalez, Eva S. Stinnesbeck, Wolfgang Stinnesbeck. 2021. Manta-like planktivorous sharks in Late Cretaceous oceans. Science 371(6535): 1253-1256.

- Zhu, Min, Xiaobo Yu, Per Erik Ahlberg, Brian Choo, Jing Lu, Tuo Qiao, Qingming Qu, Wenjin Zhao, Liantao Jia, Henning Blom & You'an Zhu (2013) The braincase and jaws of a Devonian "acanthodian" and modern gnathostome origins Nature 502, 188–193.

- Min Zhu, Per Erik Ahlberg, Zhaohui Pan, Youan Zhu, Tuo Qiao, Wenjin Zhao, Liantao Jia, Jing Lu, 2016. A Silurian maxillate placoderm illuminates jaw evolution. Science 354(6310) 334-336.

- You-an Zhu, Qiang Li, Jing Lu, Yang Chen, Jianhua Wang, Zhikun Gai, Wenjin Zhao, Guangbiao Wei, Yilun Yu, Per E. Ahlberg and Min Zhu. The oldest complete jawed vertebrates from the early Silurian of China. Nature 609, 954–958.

- Martin Brazeau and Valerie de Winter, (2015) The hyoid arch and braincase anatomy of Acanthodes support chondrichthyan affinity of 'acanthodians.' Proceedings of the Royal Society B 282: 20152210. http://dx.doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2015.2210.