Cornerstones of Scientific Thinking - check!

So far we have determined established three important cornerstones of scientific thinking:

- The Scientific Method based on hypothesis falsification

- The scientific meaning of "theory"

- The identification of common logical fallacies

A Scientific Toolbox:

Today we put a fourth cornerstone in place by identifying a set of positive habits of mind that rational evaluators of truth claims (scientists included) should employ. These are organized around ideas found in Thomas Kida's Don't Believe Everything You Think but draw on a number of sources, particularly The Demon-Haunted World: Science as a Candle in the Dark by Carl Sagan). Specific tools that you should learn are numbered. We group them for you under general headings:

Use the method. Avoid unscientific distractions:

-

1) Honest skepticism: Keep an open mind, but be skeptical of any unsubstantiated claim:

- Many propositions might be true but not all of them are. The task is to identify the false ones. We often say that to be provisionally accepted, a proposition must be both necessary and adequate to explain the observations.

- Even logically sound deductive arguments can yield flawed results if they are based on flawed premises.

- Never be persuaded not to apply honest skeptical scrutiny for any reason. ("How dare you suggest that....") True propositions will definitely be able to withstand it. Only falsehoods need fear it.

2) Substantive debate by knowledgeable proponents of all points of view: Exclusion of informed viewpoints without consideration limits the range of hypotheses under consideration and can only reduce the likelihood of arriving at the truth. But note: Participants must be knowledgeable and debate must be substantive. We are under no obligation to engage in a shouting match with any poorly informed person. (That isn't always an easy call to make. Example: Greg Paul and his art.) That said,....

3) There are no true authority figures: Scientific discourse takes place on a level playing field in which ideas are judged by their merits. Summed up in this bathroom graffito: "Ideas by merit, not by source." No good comes when an authority silences substantive debate on an issue. (Example: Artificial intelligence concepts of Marvin Minsky vs. back-propagation neural networks.)

Evaluate the quality of the evidence for a claim:

-

4) Independent confirmation of facts:

The only real way to know if an observation is repeatable is actually to repeat it.

5) Quantification: Remember, subjective observations are useless to science. Sometimes, subjectivity can creep into even detailed observations. The true proof of objectivity is often the ability to count or measure in your observations.

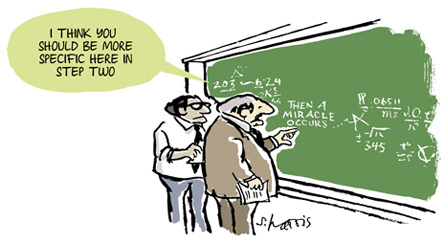

6) A chain is as strong as its weakest link: When your argument requires a chain of logical steps, each step must be valid or the whole thing is invalid.

Make sure a hypothesis can be tested:

- Until the hypothesis is tested, it is only considered speculation. (A non-falsifiable hypothesis can never be more than speculation.)

- After the hypothesis survives tests of falsification, it is tentatively accepted as true, but with the understanding that additional tests are desirable and might potentially overturn the hypothesis.

7) Falsifiability: In science you must always have a definite answer to the question, "If I were wrong, how would I know it?" If you don't, you aren't doing science. That means your hypothesis must be falsifiable - it must be possible, in principle, to know if your hypothesis is wrong. If you have no way of knowing if you are wrong. Without this, you are not doing science. Remember:

Consider alternative explanations:

8) Use more than one hypothesis: There are often many possible patterns or explanations for patterns. They should all be examined, and the quickest way to get to the answer is usually to examine them simultaneously and not to assume that they are mutually exclusive.

9) Don't get too attached to your hypotheses: The whole point of testing a hypothesis is to try to falsify it. If we don't try in earnest, then we really haven't done much. Alas, the world, including the scientific world, is full of true-believers who would never, on their own, admit that they are wrong, were their feet not held to the fire of falsifiability.

Favor simplicity:

-

Other things being equal, when presented with many plausible options, choose the the simplest (i.e., the one that requires the fewest assumptions)

10) Parsimony: When there are more than one possible solutions, the simplest one will usually be correct. This is formally known as the principle of parsimony, and also called Occam's razor.

11) Consilience: Other things being equal, choose the claim that doesn't conflict with well-established knowledge. This is sometimes refered to as the principle of consilience.

12) Proportionality: Sometimes you must balance evidence for a claim against evidence that is inconsistent with it but doesn't absolutely exclude it. Proportion your acceptance of a claim to the amount of evidence for or against a claim.